The Story of the Soldier and the Spoons

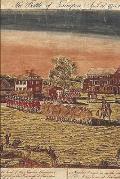

In The Battle of April 19, 1775, Frank W. Coburn included this anecdote about the aftermath of the British march:

It’s significant that the story had not surfaced in print before, even in The Hastings Memorial, an 1866 family genealogy that included entries about Samuel Hastings, his family, and their Revolutionary experiences.

Alexander Cain of Untapped History researched the Hastings family in depth for the Lexington Minute Men and his book We Stood Our Ground. He recently wrote about Samuel Hastings, Jr., again on the Historical Nerdery blog.

On the story of the wounded soldier with the spoons, Cain now warns:

About a sixth of a mile yet farther along, stood the home of Samuel Hastings, near the Lexington boundary line, yet within the town of Lincoln. Hastings was a member of Capt. [John] Parker’s Lexington Company, and was present and in line for action when [Maj. John] Pitcairn gave that first order to fire [or not].Publishing in 1912, Coburn credited this story to two great-grandsons of Samuel Hastings, Cornelius Wellington (born 1828) and Charles A. Wellington (born 1837), both members of the Lexington Historical Society. Of course, both were born over half a century after the battle.

As the British column swept along, one of the soldiers left the ranks and entered the house for plunder, unmindful of the dangers lurking in the adjoining woods and fields. As he emerged and stood on the doorstone, an American bullet met him, and he sank seriously wounded. There he lay, until the family returned later in the afternoon, and found him. Tenderly they carried him into the house, and ministered to his wants as best they could, but his wound was fatal. After his death they found some of their silver spoons in his pocket. He was buried a short distance westerly from the house.

It’s significant that the story had not surfaced in print before, even in The Hastings Memorial, an 1866 family genealogy that included entries about Samuel Hastings, his family, and their Revolutionary experiences.

Alexander Cain of Untapped History researched the Hastings family in depth for the Lexington Minute Men and his book We Stood Our Ground. He recently wrote about Samuel Hastings, Jr., again on the Historical Nerdery blog.

On the story of the wounded soldier with the spoons, Cain now warns:

There are no period records or accounts of the family encountering a wounded soldier. More importantly, the Hastings’ homestead was not located on the Boston Road near the Lincoln and Lexington lines as many 19th and 20th Century accounts claim. Instead, it appears the homestead was further in the interior of Lexington and away from the fighting.Cain’s essay then follows the younger Samuel Hastings through his capture alongside Gen. Charles Lee in late 1776. Did he return to Lexington? Check it out.