“Demagogues never were nor will be Patriots”

This was, they warned the voting public, more likely than some form of aristocracy or oligarchy leading to a tyrant gaining power.

That fear motivated George Washington to come out of retirement and chair the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, as he explained to Lafayette on 6 June 1787:

The pressure of the public voice was so loud, I could not resist the call to a convention of the States which is to determine whether we are to have a Government of respectability under which life—liberty, and property secured to us, or whether we are to submit to one which may be the result of chance or the moment, springing perhaps from anarch⟨ie⟩ Confusion, and dictated perhaps by some aspiring demagogue who will not consult the interest of his Country so much as his own ambitious views.That convention produced a blueprint for government with a stronger national chief executive than anyone had envisioned before, albeit not as strong as it would become later. And of course the Federalists felt they were the best qualified to exercise those powers.

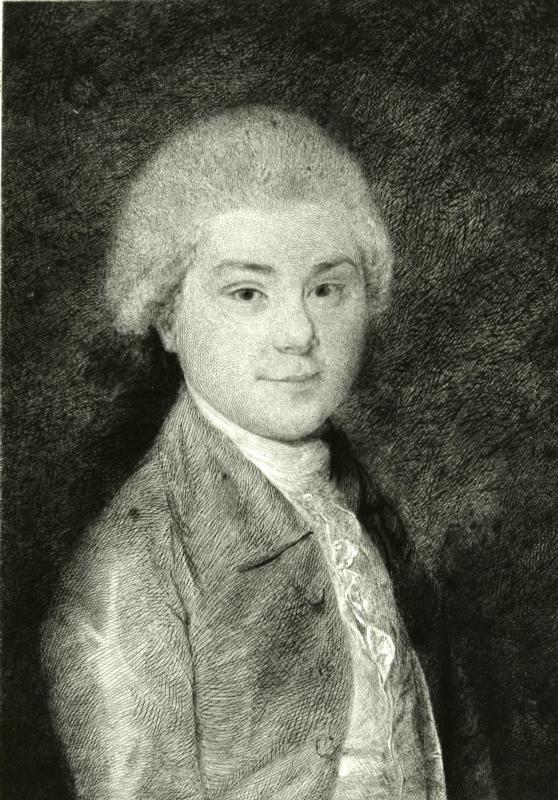

The fear of demagogues remained, now directed at any popular opposition to their policies. After negotiating a treaty with Britain that he knew would provoke complaints, John Jay wrote home to President Washington on 25 Feb 1795:

Demagogues will constantly flatter the Passions and Prejudices of the multitude; and will never cease to employ improper arts against those who will not be their Instruments. I have known many Demagogues, but I have never known one honest man among them. These are among the Evils which are incident to human Life, and none of them shall enduce me to decline or abandon Pursuits, in which I may concieve it to be my Duty to embark or persevere. All creatures will act according to their nature, and it would be absurd to expect that a man who is not upright will act like one that is.Over a decade later, Jay was a retired jurist, diplomat, and New York governor, but he still expressed distaste for politicians who played to the public in an 18 Apr 1807 letter:

All Parties have their Demagogues, and Demagogues never were nor will be Patriots—Self Interest excites and directs all their Talents and Industry; and…by that Principle they regulate their conduct towards Men and Measures—nor is this all—They not only act improperly themselves, but they diligently strive to mislead the weak the Ignorant and the unwary—as to the corrupt they like to have it so—it makes a good market for them.While I share these Federalists’ worry about demagogues, I think they directed that worry at the wrong targets, their view distorted by class prejudices and (try as they might) their own self-interests.

Firstly, the politicians the Federalists of the 1790s feared would be demagogues, such as Thomas Jefferson or even Matthew Lyon, didn’t threaten the republic, only Federalist domination of that republic.

Beyond that, history has shown that bigoted inertia was a bigger obstacle to liberty and economic growth than allowing the American government to be more responsive to the whole American people.