A Long Search for Hercules Posey

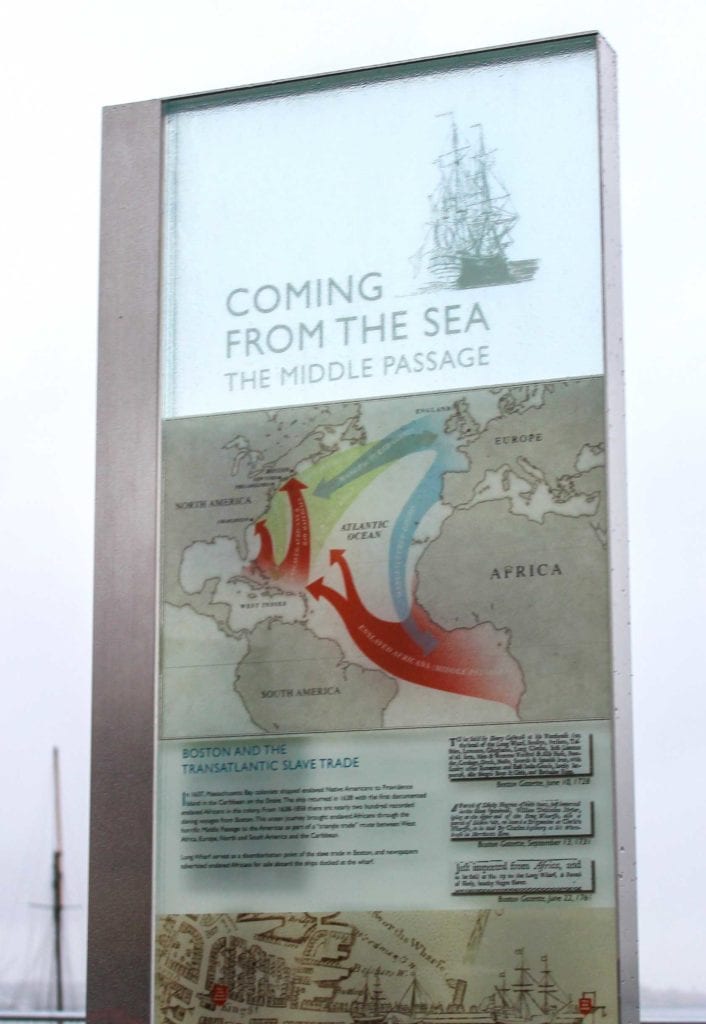

At Zagat, the chef and culinary historian Ramin Ganeshram shared the story of her research into Hercules Posey, head cook at Mount Vernon and the Presidential Mansion in Philadelphia until he freed himself from slavery.

In this article, Ganeshram describes the roots of her quest in childhood. Like me, during the Bicentennial she and her family toured the seat of the Continental Congress and other Revolutionary sites, but with a different perspective:

In 1976, I visited Philadelphia and Washington’s Mount Vernon to celebrate the American Bicentennial with my Trinidadian father. As young as I was, I could sense my father was moved as we stood on a long line to see the Liberty Bell. We didn’t know it, but as we waited, we stood on the buried remains of the President’s House where Hercules had lived.Later learning about Posey, Ganeshram started gathering more facts about him. This project took her through a picture book, cancelled at the last moment; a historical novel; experts’ realization that the painting said for decades to be Posey’s portrait was in fact nothing of the kind; and finally her discovery of records of the man in nineteenth-century New York. (In 2019 I recounted her findings and added a data point.)

No one talked about the enslaved Africans in the city of independence. It would be decades before the President’s House site was excavated as an open-air exhibit honoring them. It was a week later while visiting George Washington’s Virginia home that I began to viscerally sense this omission, although I was too young to name it. Instead, I sensed it in how my father’s mood changed, how he asked the tour guides about the enslaved people of the house and the field, and how his questions were deflected with twittering Southern charm. Later he brooded a long time at the slave quarters and the kitchen—Hercules’ kitchen. When I asked what was wrong, he just shook his head darkly. For years after, even the mention of Mount Vernon gave me a shifting sense of unease.

Ganeshram ends her essay at another location linked to Posey:

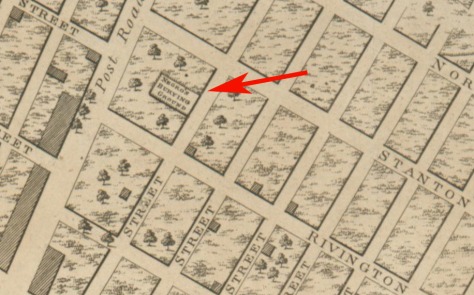

When he died of tuberculosis on May 15, 1812, at age 65, Hercules was buried at the 2nd African Burial Ground in Chrystie Street. The cemetery was overflowing its boundaries by the time of Hercules’ death. He, along with others, was likely buried under what is now pavement and roadway. When the cemetery was disinterred in the 19th century and moved to Cypress Hills in Brooklyn, some were left behind. I believe Hercules was among them.This post from the New York Cemetery Project has maps showing where the city’s Second African Burying Ground lay.

When I first visited the site in 2019, I looked around Chrystie Street with fresh eyes, seeking clues about Hercules. Seeing none, I spoke to him in my mind as I often do, for we have come a long way together. I brooded as I walked. If only I had a sign that I was on the right track. Stopping for a light at a cross-street, I looked at the curb ahead of me and saw a small white van with Hercules Dry Cleaning emblazoned on its side. I pressed on.

The former burial ground is now a private lot with an apartment building. At the southern end of Chrystie street hulks the Manhattan Bridge. Across the street is a public park where I have been encouraging New York City’s parks department to place a commemorative plaque for the Burial Ground, the once-thriving Free Black community, and for Hercules Posey—who was America’s first celebrity chef and so much more.