The Deborah Champion Story Today

Yet, as I laid out before, the letter’s historical details, language, and narrative style strongly suggest that it’s a fiction created around 1900. No one has ever come forward with an original document. The two divergent transcriptions are both said to be accurate, but I suspect the second to surface was created to correct the more obvious problems of the first.

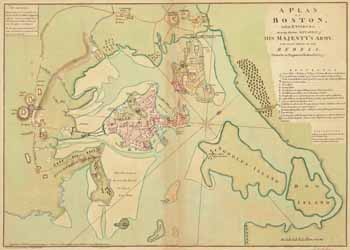

The letter was probably inspired by a tradition among descendants of Deborah’s father, Henry Champion. As put into print in 1891, that tradition implied Deborah had undertaken at least two rides, one to bring dispatches to Gen. George Washington and the other to carry a payroll past British patrols. The letter gathers all those details into one mission.

Unfortunately, the family lore had already become garbled as to Deborah’s age and marital status by the time it was printed. There doesn’t seem to be concrete evidence or independent strains in separate family lines to support the story. Thus, though there might have been a kernel of truth in the tradition of Deborah Champion’s ride, it’s impossible to sift that out in a convincing way.

Some scholars I know have taken one look at the Deborah Champion letter and recognized it as inauthentic. They’re historians used to reading real eighteenth-century correspondence, versed in the events and customs and language of that period. There are so many unreliable tales from the Colonial Revival that they weren’t surprised to encounter one more, and simply moved on to more promising material.

On the other hand, researchers with less specific experience might come across the text, look for Deborah Champion’s name in other books, find an increasing number of authors accepting the story, and conclude that the letter is reliable. After all, some fine historians have accepted it.

This series of postings appears to be the first thorough analysis of the Deborah Champion letter as a historic source. It’s the first to unearth the most dubious version of the text, the 1926 newspaper publication that said it was dated 1776, and to trace the links among the Champion descendants who shared the story in the early 1900s. Dr. Sam Forman deserves the credit for initiating the project and leading the research team, including myself, Rachel Smith, Derek W. Beck, Tamesin Eustis, and the timely assistance of Kevin Peel and Will Brooks.

Our work was possible only because of all the digital resources we’ve all gained in recent years: Google Books, newspaper scans, genealogical sites, and of course email. The internet also made it possible to publish such a detailed debunking economically. A print journal would probably be able to justify only a couple of pages warning scholars off (as the William & Mary Quarterly did with Mary Beth Norton’s warning about the Dorothy Dudley diary in 1976).

So now the question is whether the worldwide availability of the two texts of the letter, information about their publication, and our analysis can catch up to the books and websites that promulgate the letter as authentic reliable. Once someone raises doubts with a few strong points, people’s skepticism usually kicks in and they can spot a lot more holes for themselves.

At least I hope so.