“That the leaning of the writer of the above might not be mistaken…”

Yesterday I quoted most of the Boston News-Letter’s 22 Aug 1765 report on the first anti-Stamp Act protest the week before.

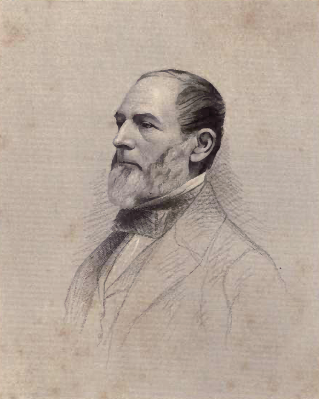

In 1856 Samuel Gardner Drake (shown here) quoted the same article at length in his History and Antiquities of Boston. He appears to have missed printer Richard Draper’s sarcastic jibes at the crowd, however. Drake wrote:

Drake’s extract included these lines from the News-Letter (with modernized capitalization and punctuation):

Whigs in Bristol, England, had formed a Union Club by 1750, pushing for political reform and the protection of liberties. In the 1760s a ship of that name was visiting Boston. New Englanders would have known what the “Union Club” stood for—and should have seen the irony of forming one in somebody else’s house.

In 1865 William V. Wells quoted that line about the “Union Club” without its context in his Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams. He went on to say those men were doubtless the same group as the “Sons of Liberty” who had organized the protest.

Later authors repeated that equation: the Sons of Liberty, the Union Club, and the “Loyall Nine” (a term from yet another source, published later) were all names for the same protest organizers identified by the Rev. William Gordon.

In fact, I haven’t found a single source besides the Boston News-Letter using the name “Union Club” that way. It doesn’t reappear in the newspapers. It doesn’t show up in John Adams’s or Samuel Adams’s writings. It doesn’t show up in John Rowe’s or John Tudor’s diaries. Given the sarcasm in the initial report, I doubt the “Loyall Nine” ever really adopted the term.

(By December 1774 a Union Club was established in Salem. It contributed something for the poor after the Boston Port Bill, and on 16 December Samuel Adams sent a thank-you letter to Samuel King. I can’t find any other period mention of that organization.)

In 1856 Samuel Gardner Drake (shown here) quoted the same article at length in his History and Antiquities of Boston. He appears to have missed printer Richard Draper’s sarcastic jibes at the crowd, however. Drake wrote:

That the leaning of the writer of the above might not be mistaken, he closed by a memorable saying of Lord Burleigh, much in use in those days, “England can never be undone but by a Parliament.” Thus the mob was encouraged, and, as by the sequel it will appear, a very partial account was given of what had taken place. The course taken by the papers under the control of the Government had some effect in producing the above, for the News-Letter had been jeered by them because it had not come out with early denunciations of the proceedings of the mob.The criticism of the News-Letter appeared in an Whiggish newspaper, not in one “under the control of the Government.” The Boston Whigs faulted Draper for not reporting on the demonstration at all; if he’d “come out with early denunciations of the proceedings of the mob,” they’d have faulted him even more vigorously.

Drake’s extract included these lines from the News-Letter (with modernized capitalization and punctuation):

The populace after this went to work on the barn, fence, garden, and dwelling-house, of the gentleman against whom their resentment was chiefly levelled [Andrew Oliver], and which were contiguous to said hill. And here, entering the house, they bravely showed their loyalty, courage, and zeal, to defend the rights and liberties of Englishmen. Here, it is said by some good men that were present, they established their Society by the name of the Union Club.In context, coming right after describing rioters breaking into Oliver’s house “to defend the rights and liberties of Englishmen,” the reference to the “Union Club” looks like another bit of Draper’s sarcasm.

Whigs in Bristol, England, had formed a Union Club by 1750, pushing for political reform and the protection of liberties. In the 1760s a ship of that name was visiting Boston. New Englanders would have known what the “Union Club” stood for—and should have seen the irony of forming one in somebody else’s house.

In 1865 William V. Wells quoted that line about the “Union Club” without its context in his Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams. He went on to say those men were doubtless the same group as the “Sons of Liberty” who had organized the protest.

Later authors repeated that equation: the Sons of Liberty, the Union Club, and the “Loyall Nine” (a term from yet another source, published later) were all names for the same protest organizers identified by the Rev. William Gordon.

In fact, I haven’t found a single source besides the Boston News-Letter using the name “Union Club” that way. It doesn’t reappear in the newspapers. It doesn’t show up in John Adams’s or Samuel Adams’s writings. It doesn’t show up in John Rowe’s or John Tudor’s diaries. Given the sarcasm in the initial report, I doubt the “Loyall Nine” ever really adopted the term.

(By December 1774 a Union Club was established in Salem. It contributed something for the poor after the Boston Port Bill, and on 16 December Samuel Adams sent a thank-you letter to Samuel King. I can’t find any other period mention of that organization.)

No comments:

Post a Comment