More Misrepresentation of James Wilson

The American Philosophical Society has just shared what might be the best blog posting of the season: Renée Wolcott’s “Spurious Sexploits: The Case of the James Wilson Diary.”

James Wilson was a Pennsylvania jurist who played important roles at the Constitutional Convention and on the first U.S. Supreme Court.

He was also prominent at the Second Continental Congress, though not in the way portrayed in the musical 1776.

The diary in question is a 1773 almanac with notes of various sorts throughout—a common eighteenth-century artifact. Originally written in black ink, those notes have faded to brown.

What makes it interesting is how some of those notes describe sexual exploits. As Wolcott explains:

That raised the possibility that Wilson chose to write those entries in a common red ink of the day, one that didn’t contain iron. Were those his “red letter days”?

Further examination under “a powerful stereomicroscope,” however, showed that the quality of the inks differed in other ways as well. There are also textual clues that the sexual lines weren’t written in 1773: word usage, lack of the long s, &c.

So now the mystery is, as Wolcott writes, “Why this forger wished to present James Wilson as a satyr.”

James Wilson was a Pennsylvania jurist who played important roles at the Constitutional Convention and on the first U.S. Supreme Court.

He was also prominent at the Second Continental Congress, though not in the way portrayed in the musical 1776.

The diary in question is a 1773 almanac with notes of various sorts throughout—a common eighteenth-century artifact. Originally written in black ink, those notes have faded to brown.

What makes it interesting is how some of those notes describe sexual exploits. As Wolcott explains:

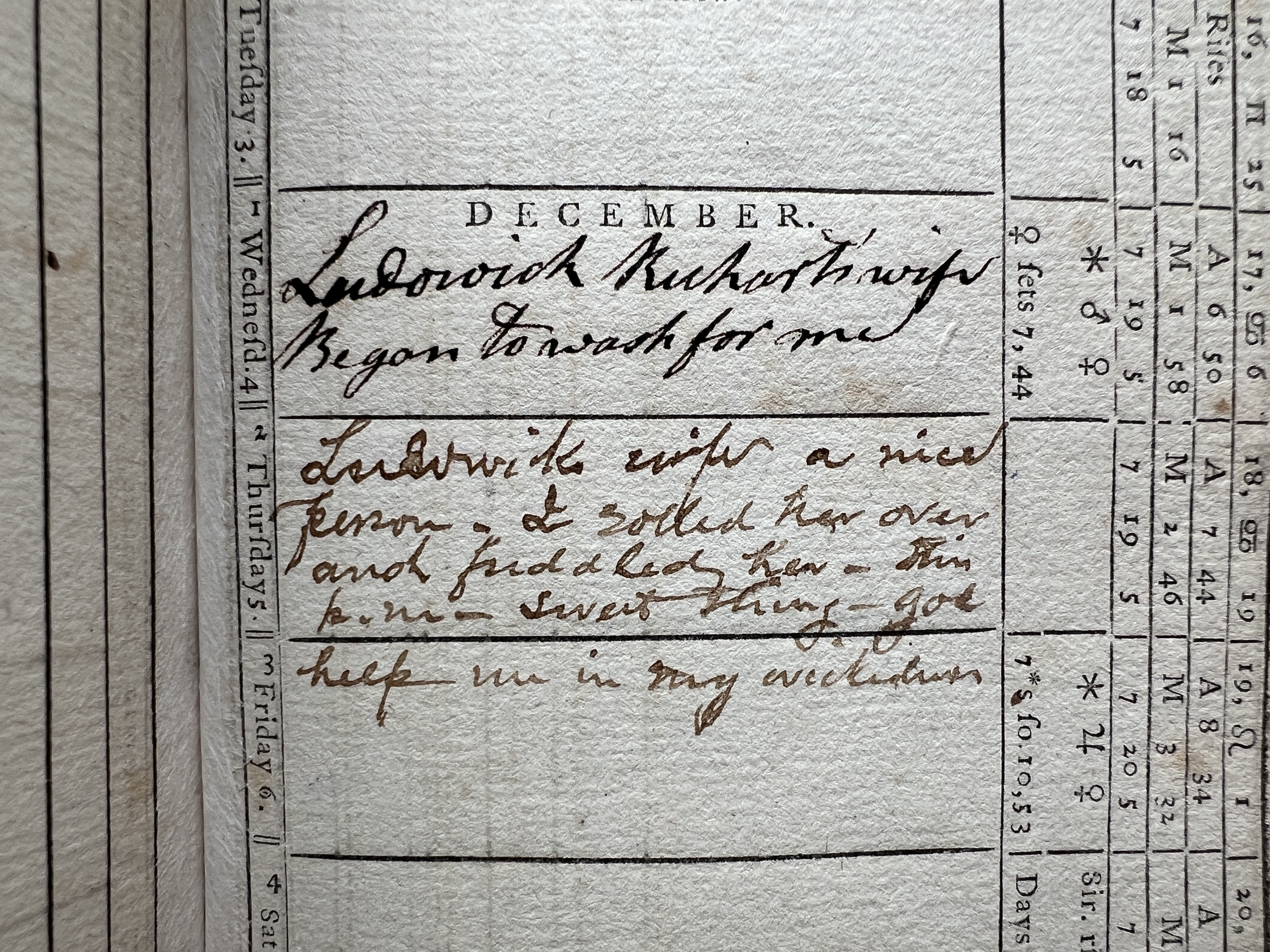

In the space dedicated to Wednesday, December 4, Wilson wrote “Ludowick Richart’s wife Began to wash for me” in his usual dark brown ink.In conserving the diary, Wolcott started with the knowledge that the six diary entries referring to sex are now a lighter brown than the innocuous business entries. She tested a sampling of marks and found that Wilson wrote most of his entries in iron gall black ink, but those remarks about sex are in a different ink.

In the space immediately below, for Thursday, December 5, the paler ink continued, “Ludowicks wife a nice person – I rolled her over and fuddled her – This p.m – sweet thing – god help me in my wickedness.”

That raised the possibility that Wilson chose to write those entries in a common red ink of the day, one that didn’t contain iron. Were those his “red letter days”?

Further examination under “a powerful stereomicroscope,” however, showed that the quality of the inks differed in other ways as well. There are also textual clues that the sexual lines weren’t written in 1773: word usage, lack of the long s, &c.

So now the mystery is, as Wolcott writes, “Why this forger wished to present James Wilson as a satyr.”

No comments:

Post a Comment