From “Loyall Nine” to “Sons of Liberty”

We have a reasonably good idea of who eight of Boston’s “Loyall Nine” were:

Within months after they started organizing anti–Stamp Act protests, the group appears to have adopted another name. Back during Parliament’s debate over that law, opponent Isaac Barré called American colonists “Sons of Liberty,” as reported to this side of the Atlantic by Jared Ingersoll. By the fall the “Loyall Nine” started using that phrase.

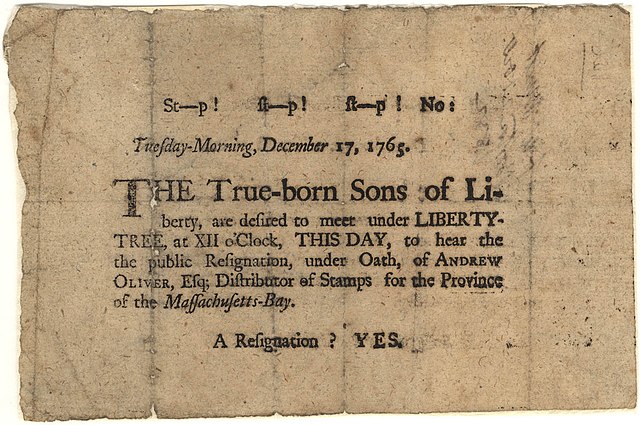

The handbills that Bass described the group printing in his December 1765 letter said: ”The True-born Sons of Liberty, are desired to meet under LIBERTY-TREE, at XII o’Clock, THIS DAY…” Evidently any man could merit that label by coming out to resist the new tax from London. In early 1766 the phrase also started to appear in newspapers in other ports.

But the group also used that term for themselves. In January 1766 John Adams called them “the Sons of Liberty.” On 15 February, Crafts wrote to Adams that “the Sons of Liberty Desired your Company at Boston Next Wensday.” Those are clearly references to a specific group, not to everyone taking a certain political stand.

It looks like the more general use won out. By August 1769, “An Alphabetical List of the Sons of Liberty who din’d at Liberty Tree [Tavern], Dorchester” included 300 names. Clearly those Sons of Liberty weren’t just the “Loyall Nine”—though all eight men listed above were there.

Nonetheless, because of some unsubstantiated claims and portrayals in popular culture, the belief persists that the Sons of Liberty was an identifiable group of activists, not a mass movement, as I’ve written before. Because of that squishiness, I tend not to use the term. But of course it’s strongly associated with the Revolution.

TOMORROW: Back to the bowl.

- John Avery, Jr., distiller and merchant

- Thomas Chase, distiller

- Thomas Crafts, Jr., painter

- John Smith, brazier

- Stephen Cleverly, brazier

- Henry Bass, jeweler

- George Trott, jeweler

- Benjamin Edes, printer

Within months after they started organizing anti–Stamp Act protests, the group appears to have adopted another name. Back during Parliament’s debate over that law, opponent Isaac Barré called American colonists “Sons of Liberty,” as reported to this side of the Atlantic by Jared Ingersoll. By the fall the “Loyall Nine” started using that phrase.

The handbills that Bass described the group printing in his December 1765 letter said: ”The True-born Sons of Liberty, are desired to meet under LIBERTY-TREE, at XII o’Clock, THIS DAY…” Evidently any man could merit that label by coming out to resist the new tax from London. In early 1766 the phrase also started to appear in newspapers in other ports.

But the group also used that term for themselves. In January 1766 John Adams called them “the Sons of Liberty.” On 15 February, Crafts wrote to Adams that “the Sons of Liberty Desired your Company at Boston Next Wensday.” Those are clearly references to a specific group, not to everyone taking a certain political stand.

It looks like the more general use won out. By August 1769, “An Alphabetical List of the Sons of Liberty who din’d at Liberty Tree [Tavern], Dorchester” included 300 names. Clearly those Sons of Liberty weren’t just the “Loyall Nine”—though all eight men listed above were there.

Nonetheless, because of some unsubstantiated claims and portrayals in popular culture, the belief persists that the Sons of Liberty was an identifiable group of activists, not a mass movement, as I’ve written before. Because of that squishiness, I tend not to use the term. But of course it’s strongly associated with the Revolution.

TOMORROW: Back to the bowl.

1 comment:

Thanks for the great post! In the novel I am writing now that begins in 1775, the Patriots in Machias, Maine (then a part of Massachusetts) called themselves Sons of Liberty, too.

Post a Comment