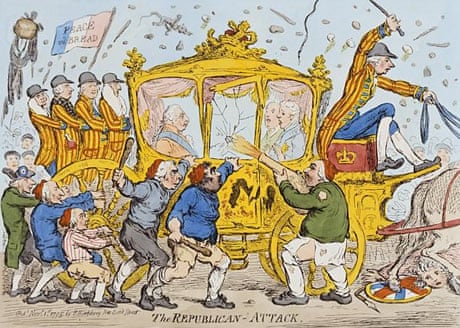

Two Attacks on George III’s Coach

Last week I wrote about George III’s gilded coach, and how some Londoners stoned it in October 1795.

It turns out this wasn’t the first time a crowd had attacked that royal coach. Or was it?

The Georgian Lords Twitter account led me to this passage from the diary of Queen Charlotte on 21 Jan 1794:

On 24 January the Oracle newspaper, also called Bell’s New World, stated:

And yet a leading establishment newspaper assured the public that the “report” circulating was mistaken, that there was no “madman” or “ruffian” to hunt down—let alone two. Publicizing an assault when there was no way to find the criminal would probably have only made the authorities look ineffectual.

In contrast, the government took quite public action when people threw stones at the king’s coach toward the end of the following year, on 29 Oct 1795. Parliament undertook an immediate investigation. The questioning of witnesses was transcribed and later published. Two men were charged:

The ministry under William Pitt took advantage of the moment to press two bills, one “for the Safety and Preservation of His Majesty’s Person and Government” and the other “for the More Effectually Preventing Seditious Meetings and Assemblies.” Those laws let the British government crack down on opponents of its war policy.

Kidd Wake went on trial in February 1796, and his fate can be seen in the title of a publication he offered for sixpence in 1801: The Case of Kidd Wake: Being a Narrative of His Sufferings, During Five Years Confinement!!! In Glocester Penitentiary House: for Hooting, Hissing, and Calling Out No War! as His Majesty was Passing in State. Among Wake’s reported sufferings was contracting tapeworms. He died in a wagon accident in 1807.

As for Edward Collins, he was eventually released without trial, but I’ve found no report on that development in the mainstream British news media. It’s tempting to say he had served his purpose for the ministry.

It turns out this wasn’t the first time a crowd had attacked that royal coach. Or was it?

The Georgian Lords Twitter account led me to this passage from the diary of Queen Charlotte on 21 Jan 1794:

To Day the Kg. went to Open the Parliament about 3 a Clock. in going there were two attempts made at throwing a Stone at the Kg. the first broke the Side Glass of the Coach, & the Second was thrown from behind & fell over the Coachmans Head.You can view the actual diary page here.

On 24 January the Oracle newspaper, also called Bell’s New World, stated:

some daring ruffian threw a stone at his Majesty…which broke the coach window. We have not yet had the pleasure to hear of the villain’s apprehension.However, the Times of London had reported on 23 January:

Tuesday, as his Majesty was going in state to the House of Peers, one of the halberts of the Yeomen struck against the window of the King’s coach and smashed it. Happily no mischief was occasioned, but the circumstances gave rise to a report of some madman having thrown a stone at the window, which we are happy to contradict.Was the queen correct in recording an attack on the royal coach? It looks like she wasn’t there, but of course she would have heard from the king. It certainly looks like he was convinced people had attacked him with stones.

And yet a leading establishment newspaper assured the public that the “report” circulating was mistaken, that there was no “madman” or “ruffian” to hunt down—let alone two. Publicizing an assault when there was no way to find the criminal would probably have only made the authorities look ineffectual.

In contrast, the government took quite public action when people threw stones at the king’s coach toward the end of the following year, on 29 Oct 1795. Parliament undertook an immediate investigation. The questioning of witnesses was transcribed and later published. Two men were charged:

- Edward Collins, “Keeper of an Eating-house,” accused by an eyewitness of throwing a stone at the king, a crime of high treason.

- Kidd Wake, journeyman printer, heard to shout “No war!” but not seen to throw anything, and thus charged with “a misdemeanor in hissing and hooting the king in a riotous manner.”

The ministry under William Pitt took advantage of the moment to press two bills, one “for the Safety and Preservation of His Majesty’s Person and Government” and the other “for the More Effectually Preventing Seditious Meetings and Assemblies.” Those laws let the British government crack down on opponents of its war policy.

Kidd Wake went on trial in February 1796, and his fate can be seen in the title of a publication he offered for sixpence in 1801: The Case of Kidd Wake: Being a Narrative of His Sufferings, During Five Years Confinement!!! In Glocester Penitentiary House: for Hooting, Hissing, and Calling Out No War! as His Majesty was Passing in State. Among Wake’s reported sufferings was contracting tapeworms. He died in a wagon accident in 1807.

As for Edward Collins, he was eventually released without trial, but I’ve found no report on that development in the mainstream British news media. It’s tempting to say he had served his purpose for the ministry.

No comments:

Post a Comment