Looking at Lexington and Concord through Eighteenth-Century Eyes

Last month Alexander Cain at Historical Nerdery announced a resource for people researching the Battle of Lexington and Concord ahead of next spring’s Sestercentennial: a list of links to eyewitness accounts of the day.

That listing will be very useful, and it can grow. Perforce these are texts that have been digitized in one way or another. I’m sure that more lurk within books, newspapers, and letters. It’s a matter of ferreting them out and/or digitizing them in usable forms.

For instance, here is the list’s link to Gen. Thomas Gage’s instructions to Lt. Col. Francis Smith for the march to Concord on 18–19 April.

We also have what appears to be Gage’s notes or first draft of those instructions, quoted in General Gage’s Informers (1932) by Allan French. A digital version of that book can be borrowed from the Internet Archive, at least for now. Look on pages 29–30.

Since the Massachusetts Historical Society has scanned merchant John Rowe’s diaries, we can see his response to the news coming into Boston here. A transcription of what a descendant thought were the most important parts of that diary was published a century ago. Among the details one can find only in the handwritten journal is that on 20 April Capt. John Linzee, R.N., dined and spent the evening at Rowe’s house after fending off an attack on his ship on the Charles River.

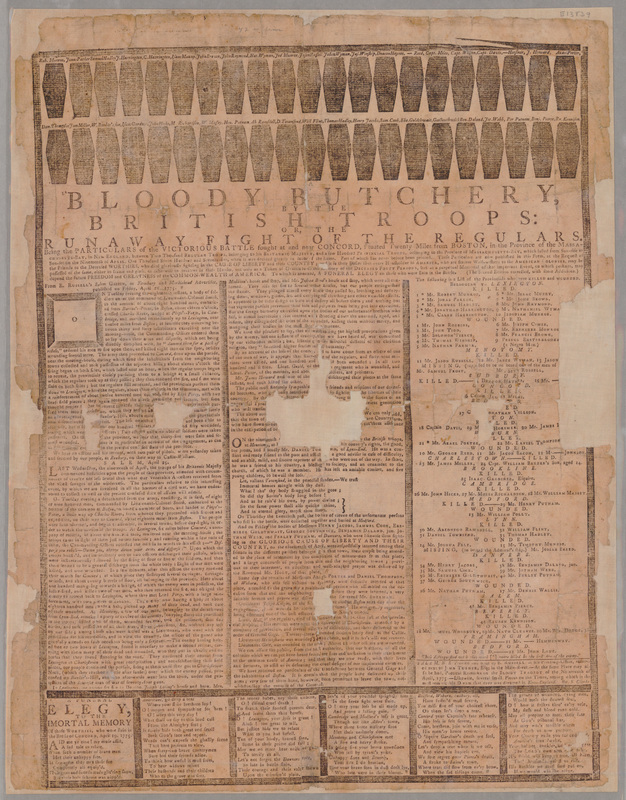

It’s possible to identify the sources of some anonymous accounts. One resource on the list, Ezekiel Russell’s “Bloody Butchery by the British Troops” broadside, includes text headlined “SALEM, April 25.” Those paragraphs commence: “LAST Wednesday, the nineteenth of April, the troops of his Britannic Majesty commenced hostilities upon the people of this province…”

The preceding paragraphs come with a source citation—not coincidentally, to Russell’s own Salem Gazette newspaper. But Russell didn’t give his competition publicity by revealing that he took the second and longer passage from Samuel Hall’s Essex Gazette for 25 April. That text was later imperfectly transcribed in Peter Force’s American Archives.

The 3 May Massachusetts Spy on the list includes an unsourced story about what happened “When the expresses [from Boston] got about a mile beyond Lexington.” That story matches one that William Dawes’s family recalled hearing from him, revealing that Dawes was probably printer Isaiah Thomas’s source.

Among the lately revealed visual resources is this hand-drawn map in the Library of Congress. I’m convinced by Ed Redmond’s hypothesis that Ens. Henry DeBerniere created this map ahead of the march to Concord. It thus offers a look at what British army officers knew of the countryside west of Boston. (I discussed details of that map starting here.)

TOMORROW: A source from May 1775.

That listing will be very useful, and it can grow. Perforce these are texts that have been digitized in one way or another. I’m sure that more lurk within books, newspapers, and letters. It’s a matter of ferreting them out and/or digitizing them in usable forms.

For instance, here is the list’s link to Gen. Thomas Gage’s instructions to Lt. Col. Francis Smith for the march to Concord on 18–19 April.

We also have what appears to be Gage’s notes or first draft of those instructions, quoted in General Gage’s Informers (1932) by Allan French. A digital version of that book can be borrowed from the Internet Archive, at least for now. Look on pages 29–30.

Since the Massachusetts Historical Society has scanned merchant John Rowe’s diaries, we can see his response to the news coming into Boston here. A transcription of what a descendant thought were the most important parts of that diary was published a century ago. Among the details one can find only in the handwritten journal is that on 20 April Capt. John Linzee, R.N., dined and spent the evening at Rowe’s house after fending off an attack on his ship on the Charles River.

It’s possible to identify the sources of some anonymous accounts. One resource on the list, Ezekiel Russell’s “Bloody Butchery by the British Troops” broadside, includes text headlined “SALEM, April 25.” Those paragraphs commence: “LAST Wednesday, the nineteenth of April, the troops of his Britannic Majesty commenced hostilities upon the people of this province…”

The preceding paragraphs come with a source citation—not coincidentally, to Russell’s own Salem Gazette newspaper. But Russell didn’t give his competition publicity by revealing that he took the second and longer passage from Samuel Hall’s Essex Gazette for 25 April. That text was later imperfectly transcribed in Peter Force’s American Archives.

The 3 May Massachusetts Spy on the list includes an unsourced story about what happened “When the expresses [from Boston] got about a mile beyond Lexington.” That story matches one that William Dawes’s family recalled hearing from him, revealing that Dawes was probably printer Isaiah Thomas’s source.

Among the lately revealed visual resources is this hand-drawn map in the Library of Congress. I’m convinced by Ed Redmond’s hypothesis that Ens. Henry DeBerniere created this map ahead of the march to Concord. It thus offers a look at what British army officers knew of the countryside west of Boston. (I discussed details of that map starting here.)

TOMORROW: A source from May 1775.

4 comments:

Hey J.L. - Saw Salem posted in the hyperlinks (imagining hyperlinks on the battle green - a bit of 'Through The Looking Glass at Lexington and Concord' - seemingly I digress, however, given the following 'Bewitched' tv show script (essentially) I am on my Father's side a descendent of Jonathan Harrington, and Susannah Martin on my Mother's side. I'm basically New England.

Thanks for this John! As well as thanks to Charlie Bahne for his comments and investigations from posts 3 years ago that I just found in your links. Fascinating information and insight!

It is unfortunate that the surviving map attributed to Ensign DeBerniere does not include the alternate route through Lexington and Menotomy that he and Capt William Brown took on their return to Boston, because it leaves a puzzle about where on that route was the "one very bad place" that DeBerniere describes in his written report to Gage. DeBerniere's sentence is a bit garbled, but he is referring to some location between Lexington and Menotomy center. A good guess would be those locations where the main road is hemmed in to the south by sharply-rising hills, and on the north by wetlands and the Mill Brook. A good candidate would be near the current Lexington/Arlington border. But that is just a guess. Are there better candidates that a soldier would describe as "one very bad place"?

DeBerniere may have made this map before his 20 Mar 1775 mission to Concord. Which means there might have been, or even might be, another map showing the road through Cambridge, Menotomy, Lexington, and Lincoln to Concord.

Post a Comment