“In free countries, the law ought to be king”

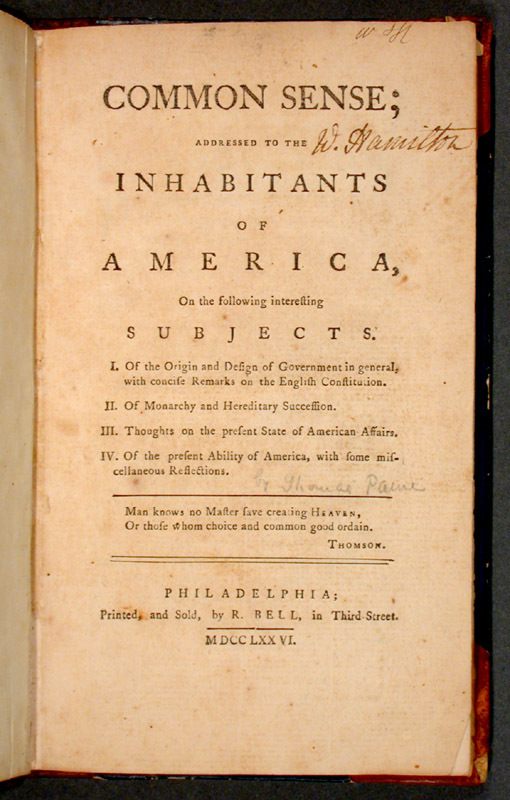

Next month sees the Sestercentennial of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, printed by Robert Bell in Philadelphia on 9 January (to judge by the first newspaper advertisement the next day) and then reprinted at the end of the month because of popular demand.

The New York Times has observed the occasion by publishing an appreciation by Boston University professor Joseph Rezek, “The Pamphlet That Has Roused Americans to Action for 250 Years.”

Rezek’s a literature scholar, so he pays particular attention to Paine’s rhetorical style. Here’s a taste:

Here’s the link.

The New York Times has observed the occasion by publishing an appreciation by Boston University professor Joseph Rezek, “The Pamphlet That Has Roused Americans to Action for 250 Years.”

Rezek’s a literature scholar, so he pays particular attention to Paine’s rhetorical style. Here’s a taste:

The first section of “Common Sense” narrates the origins of government with a classic Enlightenment experiment, asking: What was it like in the state of nature, before governments were instituted among people? “Let us suppose a small number of persons settled in some sequestered part of the earth” in a “state of natural liberty,” Paine wrote, sounding like a schoolteacher. Then kings arrive, like snakes in the garden.Of course, it’s not just the lèse-majesté insults that made Common Sense powerful, as shocking as they probably were to some British colonists. It was how Paine wielded them in service of compelling political ideas, urging Americans to put their principles of liberty into practice. A monarchist could toss around epithets and still have no better argument than “Because the king said so.”

“Mankind being originally equals,” Paine went on, their “equality could only be destroyed by some subsequent circumstance.” Look at the “present race of kings,” he declared, and “we should find the first of them nothing better than the principal ruffian of some restless gang.” Eager to make his ideas intelligible to readers who had never philosophized before, Paine used imagery he thought they could relate to.

Ripping up monarchy by the roots, he asserted that William the Conqueror did not establish an “honorable” origin for English kings when he invaded in 1066. “A French bastard landing with an armed banditti, and establishing himself king of England against the consent of the natives, is in plain terms a very paltry rascally original. It certainly hath no divinity in it.” This frank and gritty language is from the tavern, not the library.

In 1776, Paine looked toward the future. Today, many Americans are looking to the past to help navigate what really does feel like “a new era for politics.” Right after Paine declared “the law is king,” he also qualified that statement: “In free countries, the law ought to be king.” Laws in the United States have often been unjust, and just laws have often been unequally enforced. Perhaps Paine understood that the idealistic political experiment he hoped to help launch would always be a work in progress.Because there will always be snakes. Most of us know damn well they’re snakes, and most don’t get taken in.

Here’s the link.

2 comments:

Thank you for another year of helping to protect us all from snakes.

Happy Holidays.

"Let us suppose a small number of persons settled in some sequestered part of the world..." The Pilgrims came fairly close to that description, and the result was the Mayflower Compact, the seed of the New England town meeting.

Post a Comment