“The People are to be left to use their own Discretion”

The Liberty riot of 10 June 1768 wasn’t just about the seizure of John Hancock’s sloop for alleged Customs violations. It was also about how H.M.S. Romney, which helped in that seizure, had been impressing sailors in Boston harbor.

Of course, it was a lot easier to threaten Customs officers than to threaten a 50-gun warship. By Sunday, Collector Joseph Harrison wrote, he was the only top Customs official in town, “all the rest having taken shelter either on board the Man of Warr or gone into the Country”—and he had stayed in bed for two days recovering from his injuries instead of venturing out.

Boston’s Whig politicians were trying to calm the town—or at least to make it look calm. As in late 1765, when the Stamp Act riots both served the purposes of the elite and made them nervous, gentlemen sought a way to end the unrest before it harmed Boston’s reputation.

One idea was that the Customs service would return the Liberty to Hancock in exchange for a promise that if he lost the smuggling case in court he’d surrender it to the government. That didn’t work, for two reasons. First, the Customs Commissioners didn’t like the way the offer was delivered:

The second problem was that Hancock himself soured on the idea of compromise. I think he was waking to the instincts that would make him a very successful politician and an unsuccessful businessman. Getting the Liberty back would let him keep making money with it. Not getting it back would make him a political martyr, a hero of the waterfront. So the sloop remained anchored beside the warship, protected from rescue by its guns.

Gov. Francis Bernard had met with his Council on 11 June, but heard “no apprehension in the Council that there would be a repetition of these violences,” so he had gone off to his country house in Jamaica Plain. But by Sunday he was receiving alarmed reports from the Commissioners like this one:

The governor later wrote:

But Bernard and the Council weren’t the only men worried about further violence. By afternoon, there was a printed handbill being distributed around town:

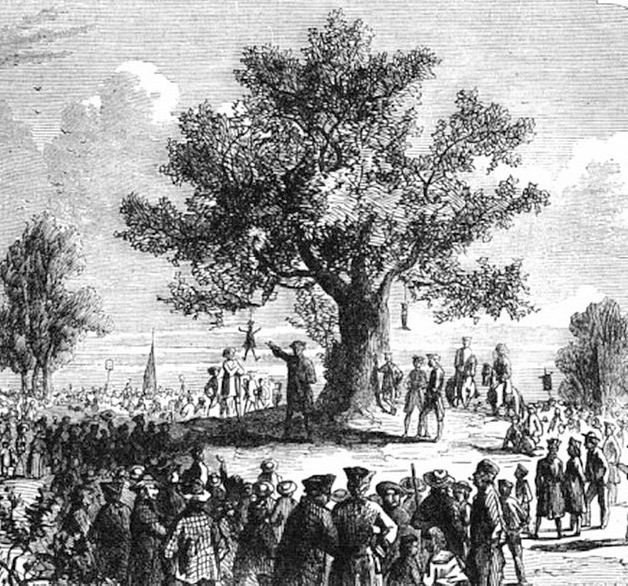

On Tuesday, 14 June, “vast Numbers of the Inhabitants” gathered at Liberty Tree under the British flag. Since the weather was “wet and uncomfortable,” they moved to Faneuil Hall. Someone proposed making this gathering an official town meeting, so the selectmen sent out a summons to convene at 3:00. So many men arrived that the crowd moved on to the Old South Meeting-House.

James Otis, Jr., presided over what the official minutes called “very cool and deliberate Debates upon the distressed Circumstances of the Town.” The meeting chose large committees to express Boston’s grievances—to present a petition to Gov. Bernard; to send a letter to Dennis Deberdt, the Massachusetts House’s lobbyist in London; and to draft a resolution protesting the Customs officers’ action. And then the first committee, again led by Otis, headed out to the governor’s house.

TOMORROW: Gov. Bernard’s response.

Of course, it was a lot easier to threaten Customs officers than to threaten a 50-gun warship. By Sunday, Collector Joseph Harrison wrote, he was the only top Customs official in town, “all the rest having taken shelter either on board the Man of Warr or gone into the Country”—and he had stayed in bed for two days recovering from his injuries instead of venturing out.

Boston’s Whig politicians were trying to calm the town—or at least to make it look calm. As in late 1765, when the Stamp Act riots both served the purposes of the elite and made them nervous, gentlemen sought a way to end the unrest before it harmed Boston’s reputation.

One idea was that the Customs service would return the Liberty to Hancock in exchange for a promise that if he lost the smuggling case in court he’d surrender it to the government. That didn’t work, for two reasons. First, the Customs Commissioners didn’t like the way the offer was delivered:

a verbal Message from the People by a Person of Character to this Effect “That if the Sloop that was seized was brought back to Mr. Hancock’s Wharf, upon his giving Security to answer the Prosecution, the Town might be kept quiet”; Which Message appearing to Us as a Menace, we applied to Capt. [John] Corner to take Us on board His Majesty’s ShipCommissioners John Robinson, Henry Hulton, William Burch, and Charles Paxton were all on the Romney by Sunday.

The second problem was that Hancock himself soured on the idea of compromise. I think he was waking to the instincts that would make him a very successful politician and an unsuccessful businessman. Getting the Liberty back would let him keep making money with it. Not getting it back would make him a political martyr, a hero of the waterfront. So the sloop remained anchored beside the warship, protected from rescue by its guns.

Gov. Francis Bernard had met with his Council on 11 June, but heard “no apprehension in the Council that there would be a repetition of these violences,” so he had gone off to his country house in Jamaica Plain. But by Sunday he was receiving alarmed reports from the Commissioners like this one:

some of the Leaders of the People had persuaded them in an Harangue to desist from further Outrages till Monday Evening, when the People are to be left to use their own Discretion, if their Requisitions are not complied with.Bernard gave permission for the Commissioners, Harrison and his family, and other Customs men to be admitted to the safety of Castle William. He called an emergency Council meeting for Monday morning.

The governor later wrote:

Before I went to Council, the Sheriff [Stephen Greenleaf] came to inform me that there was a most violent and virulent paper stuck up upon Liberty Tree, containing an Invitation to the Sons of Liberty to rise that Night to clear the Country of the Commissioners & their Officers, to avenge themselves of the Officers of the Custom-house, one of which was by name devoted to death:In another letter Bernard said that paper invited the Sons of Liberty “to meet at 6 o’ clock to clear the Land of the Virmin which are come to devour them &ca. &ca.”

There were also some indecent Threats against the Governor, if he did not procure the release of the Sloop which was seized.

But Bernard and the Council weren’t the only men worried about further violence. By afternoon, there was a printed handbill being distributed around town:

Boston, June 13th, 1768.That message came from street-level political leaders like the Loyall Nine who had organized the first anti-Stamp demonstration in 1765 and tried to steer most protests since. The handbill was most likely a product of Edes and Gill’s print shop. It superseded the call for an uprising on Monday night; as the 16 June Boston News-Letter reported, “the Expectation of this Meeting kept the Town in Peace.”

The Sons of Liberty.

Request all those, who in this time of oppression & distraction, wish well to, & would promote the peace, good order & security of the Town & Province, to assemble at Liberty Hall, under Liberty Tree, on Tuesday the 14th. instant, at Ten O’Clock forenoon precisely.

On Tuesday, 14 June, “vast Numbers of the Inhabitants” gathered at Liberty Tree under the British flag. Since the weather was “wet and uncomfortable,” they moved to Faneuil Hall. Someone proposed making this gathering an official town meeting, so the selectmen sent out a summons to convene at 3:00. So many men arrived that the crowd moved on to the Old South Meeting-House.

James Otis, Jr., presided over what the official minutes called “very cool and deliberate Debates upon the distressed Circumstances of the Town.” The meeting chose large committees to express Boston’s grievances—to present a petition to Gov. Bernard; to send a letter to Dennis Deberdt, the Massachusetts House’s lobbyist in London; and to draft a resolution protesting the Customs officers’ action. And then the first committee, again led by Otis, headed out to the governor’s house.

TOMORROW: Gov. Bernard’s response.

No comments:

Post a Comment