Richard Fry’s Greatest Scheme

Under his contract for the paper mill with Samuel Waldo and Thomas Westbrook, Fry had to pay £64 a year. But making paper on the Maine frontier didn’t bring in huge profits, and the whole province was in a cash crunch. Fry managed to send his landlords fifty reams of paper in place of specie, but that wasn’t £64 in cash, was it?

Waldo and Westbrook sued Fry and won a judgment of £70. They had the sheriffs in Maine seize the paper-making equipment. And they had Fry clapped into the Boston jail as a debtor around the start of 1737. In response, Fry claimed that Waldo and Westbrook had taken that action only after they had tried to buy him out and he refused.

Waldo recruited another man to continue the paper manufactory as an employee. Then he turned on Westbrook, forcing him out of the partnership. Calling himself “hereditary lord of Broad Bay,” Waldo recruited more settlers in Europe.

Among the people who came to America at Waldo’s invitation were the German ancestors of Christopher Seider. However, whenever Britain went to war with France, which happened in 1744 and again in 1757, the Maine frontier became a risky place to live and the settlements emptied out. Waldo died in 1759. Some of his holdings descended to his daughter Hannah and then to her daughter Lucy, wife of Henry Knox.

Meanwhile, back in the Boston jail, Richard Fry produced a steady stream of petitions complaining about his Maine landlords, the sheriff and undersheriff who’d taken his stuff, and the jailer who’d locked him up.

On 22 May 1739 Fry placed yet another advertisement in the New-England Weekly Journal:

This is to inform the Publick, that there is now in the Press, and will be laid before the Great and General Court, a Paper Scheme, drawn for the Good and Benefit of every individual Member of the whole Province; and what will much please his Royal Majesty; for the Glory of our King is in the Happiness of his Subjects: And every Merchant in Great Britain that trades to New-England, will find their Account by it; and there is no Man that has the least Shadow or Foundation of Common Reason, but must allow the said Scheme to be reasonable and just:What was he on about now? Fry was issuing A Scheme for a Paper Currency to solve the specie crisis and promote the local economy. Backing up the new printed money, he wrote, would be the output of “Twenty Mills” built around Boston harbor. When Fry had first announced his scheme the previous August, even calling a meeting of investors at the Green Dragon Tavern, he had only seventeen mills in mind.

I have laid all my Schemes to be proved by the Mathematicks, and all Mankind well knows, Figures will not lye; and notwithstanding the dismal Idea of the Year Forty One, I don’t doubt the least seeing of it a Year of Jubile, and in a few Years to have the Ballance of Trade in Favor of this Province from all Parts of the Trading World; for it’s plain to a Demonstration, by the just Schemes of Peter the Great, the late Czar of Muscovy, in the Run of a few Years, arrived to such a vast Pitch of Glory, whose Empire now makes as grand an Appearance as any Empire on the Earth, which Empire for Improvement, is no ways to be compared with this Royal Majesty’s Dominions in America.

I humbly beg Leave to subscribe myself,

A true and hearty Lover of New-England,

Richard Fry.

Boston Goal, May 1739.

One might question the value of economic advice from a man who had gone bankrupt in England and was in jail for debt. But those circumstances didn’t daunt Fry. We can read his proposal, plus a couple of the petitions he wrote in the same years, in this book. Other documents from him are in the Clements Library.

Fry’s scheme wasn’t the only attempt to address the province’s specie shortage. In 1740, Boston businessmen set up the Massachusetts Land Bank, which issued private paper currency based on land holdings. The royal government and its supporters, led by Thomas Hutchinson, worked to stifle that enterprise, and in 1741 Parliament outlawed it. Some historians have traced the enmity between Hutchinson and Samuel Adams, whose father was a Land Bank investor, to that controversy.

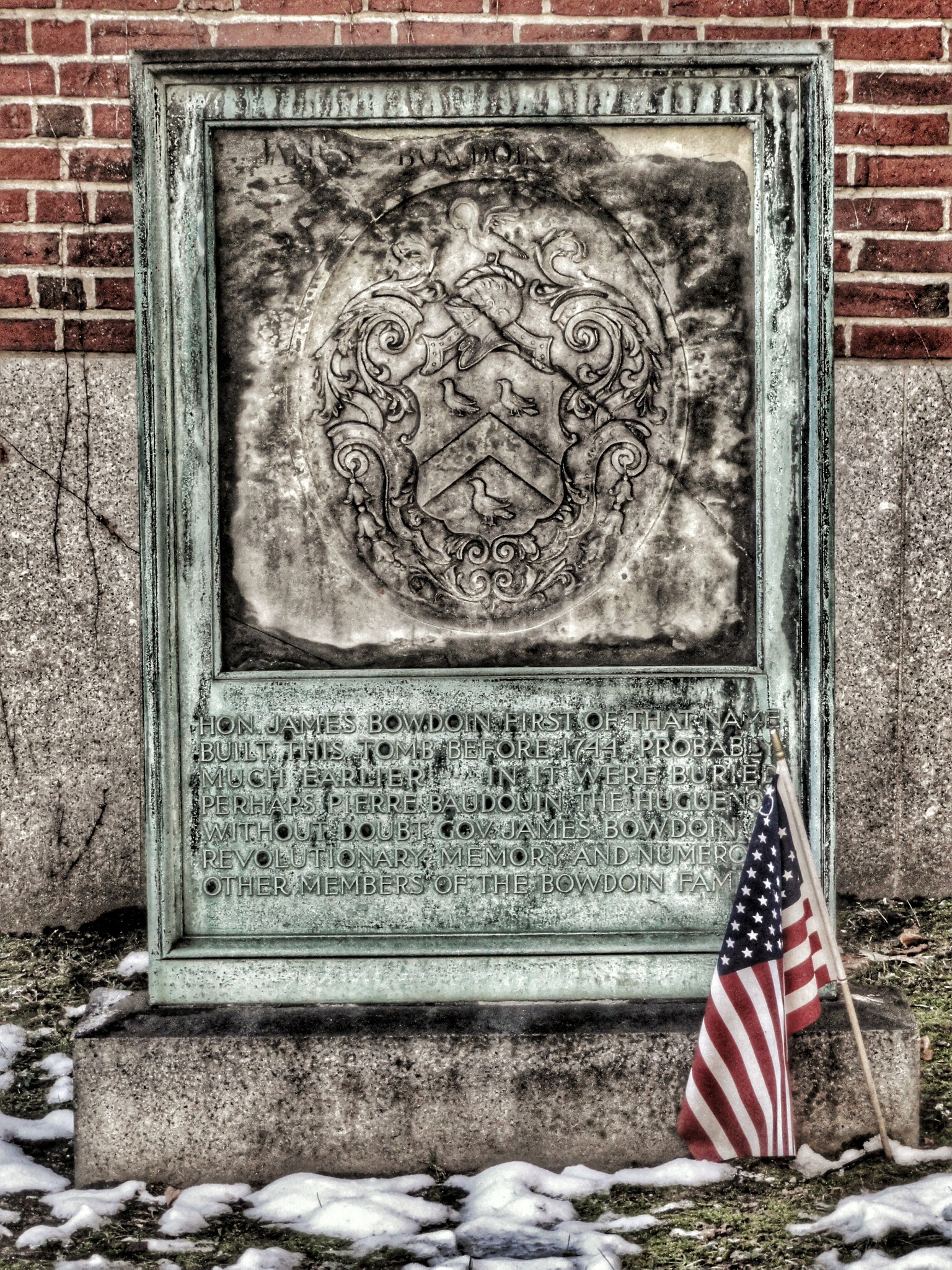

Fry of course saw nothing wrong with paper currency (and one suspects he hoped to win the contract to supply the paper). But he no doubt preferred his own approach to issuing it. And as long as the provincial authorities opposed the Land Bank, he was ready to take advantage of that. In December 1740 Fry pointed out to Gov. Jonathan Belcher and his Council that his jailer was dealing in Land Bank currency. (A sample shown above.)

Richard Fry died in 1745, his finances still a mess. He left a wife and at least one child.