Last week’s postings showed how descendants of

Henry Champion, particularly women who had

joined the Daughters of the American Revolution, promulgated the dubious

Deborah Champion letter in the early 1900s. They told the story at meetings, sent copies to other chapters, and probably shared a copy to the authors of

The Pioneer Mothers of America.

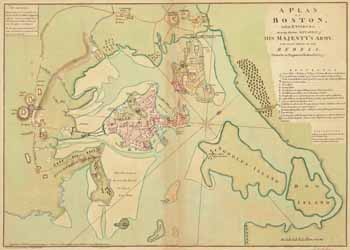

This week’s postings have shown how the

text of that letter changed over time, how its

details don’t conform to facts about the

siege of Boston, how it reads like historical fiction. Most of the Champion relatives could have been sincerely duped about the letter’s authenticity. But someone was working to maintain the fraud.

Interestingly, those women didn’t need the evidence of the Deborah Champion letter to join the D.A.R. Their common ancestor Henry Champion is well documented as a commissary general for the

Continental Army, qualifying all his descendants for membership.

His son, also named Henry, was a high officer in the army, mentioned in

George Washington’s correspondence. The Champion men already offered an authentic Revolutionary heritage.

What’s more, the Champion family remained prominent in Connecticut. The commissary general’s house is preserved as the headquarters of the

Colchester Historical Society. The Connecticut Historical Society holds a

collection of his and his son’s papers. (More are

at the Litchfield Historical Society.) Deborah Champion’s husband,

Samuel Gilbert, was a respected state legislator and jurist, and their son

Peyton R. Gilbert’s papers are at Yale.

But this letter provided a Revolutionary heritage for the Champion

women—not just Deborah, who supposedly performed a ride to rival

Paul Revere’s, but also the women who preserved and shared her story over a century later. It might have been particularly meaningful for women in branches of the family who had moved away from Connecticut. The most likely candidate for writing the letter was Mary Rebecca Adams Squire of Ohio and Pennsylvania, who first received praise for sharing the “charming tale” in 1902 and supplied a version to another branch of the family in the following decade.

The letter portrays Deborah as brave, patriotic, dedicated to her father and General Washington, and

active. She’s not a “stay at home” focused wholly on feminine

handcrafts. She steps into the traditionally male role as rider. In that respect, the Deborah Champion story is similar to the stories of

Emily Geiger (first published in 1832, no contemporaneous documentation),

Abigail Smith (first published in 1864, refuted by family documents), and

Sybil Ludington (first published in 1880, no contemporaneous documentation).

The story of her ride to Boston made Deborah Champion a heroine that later generations of Americans could relate to: a seventeen-year-old loyal daughter undertaking a dangerous mission for Gen. Washington. No matter that she was actually

twenty-two years old and married by the (earliest) date of the letter. No matter that the letter is full of improbable details and language.

In 1980, two of Deborah Champion’s descendants donated a

fur-lined red cloak to the Connecticut Historical Society. In its newsletter the society reported the “family tradition” that Deborah “wore it when she rode through British lines in 1775, carrying dispatches to General Washington.” Yet even with all its detailed descriptions of clothing, the letter doesn’t describe that fur-lined red cloak.

I asked

Lynne Bassett, an expert on historic textiles, about that garment. She replied that it appears “entirely authentic. It’s made of red wool broadcloth with shag trimming the edges. All of the construction details are right.” It’s a much more impressive artifact than we have from the vast majority of eighteenth-century American women. But without the dramatic story provided by the dubious letter, it would still be an empty cloak.

TOMORROW: The Deborah Champion revival.