Another question about Col.

Henry Knox’s mission to northern

New York to collect

artillery for the

siege of Boston is how many pieces he brought. And how many did he leave behind?

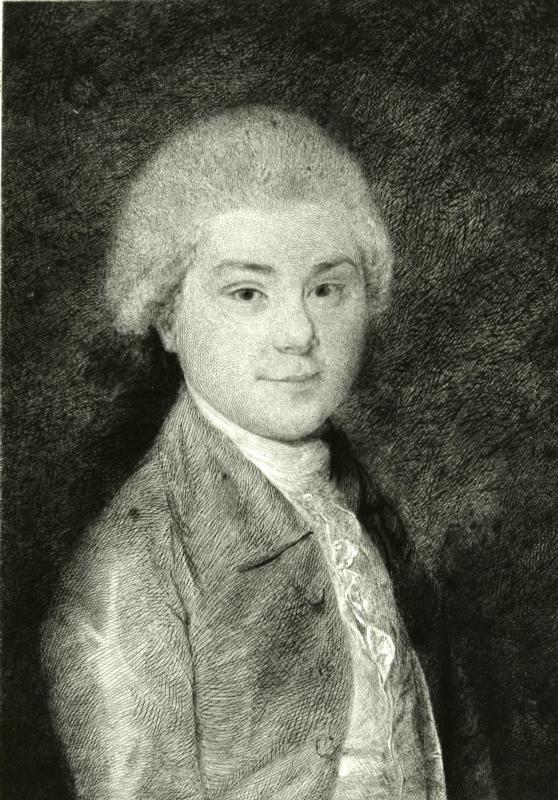

We have a couple of counts of artillery-pieces in the region from Gen.

Philip Schuyler:

Schuyler first counted 54 cannon at Fort Ti with sizes ranging from four-pounders to eighteen-pounders, but 29 of those were in a category called “Bad cannon.” By December Schuyler was counting 53 cannon in all. There were other artillery pieces as well, including swivel guns and mortars. The general sent some weapons north into

Quebec with Gen.

Richard Montgomery.

Henry Knox left at least three different listings of the artillery pieces he decided to transport back. The first, dated 10 Dec 1775, was

transcribed in his earliest biography, by Francis S. Drake. It includes 59 pieces of artillery, including 43 cannon and 16 mortars of different sorts. Knox also determined that one brass cannon Schuyler had labeled an eighteen-pounder was instead a twenty-four-pounder; the difference in bore appears to have been less than half an inch.

On 17 December, Knox sent Gen. Washington a

list of the guns he planned to bring east, probably so that Massachusetts

blacksmiths could start making shot for them. That list contained only 55 guns—he left off 4 twelve-pounders from his earlier list.

Drake also transcribed the heading of Knox’s expense report for this trip:

For expenditures in a journey from the camp round Boston to New York, Albany, and Ticonderoga, and from thence, with 55 pieces of iron and brass ordnance, 1 barrel of flints, and 23 boxes of lead, back to camp (including expenses of self, brother, and servant), £520.15.8¾.

So we might think the colonel transported 55 cannon to Boston, including 43 cannon. But on 5 January he

told Gen. Washington, “We got over 4 more dble fortified 12 pounders after my last to your excellency.” So his count was back to 59. Why Knox mentioned only 55 on his expense report is a mystery, but presumably his expenses were the same.

Yet another Knox document was transcribed in the first volume of the

Harvard Illustrated Magazine, published in 1900.

Knox evidently made these notes during his journey, recording what ordnance went on a scow and what on a

periauger. There are overlapping listings here, but at that point the freight included “42 Cannon of different Sizes” and “16 Mortars.”

Those numbers match the

inventory that I quoted yesterday from

John Adams, who viewed the train of artillery in

Framingham in January 1776. (Of course, an editorial note indicates that the editors of the Adams papers used the Knox papers as a reference, so we should expect them to match.)

We also have Knox’s diary for the first part of his trip, and that tells us that he

lost one cannon along the way. On the afternoon of 4 January, he wrote, he was “much alarm'd by hearing that one of the heaviest Cannon had fallen in to the [Mohawk] River at Half Moon Ferry.”

Three days later, near Albany, another cannon went “fell into the River notwithstanding the precautions we took.” Knox and the locals managed to get that gun out of the water the next day, but he’d had to leave the first sunken gun behind. That explains why he set out with one more iron eighteen-pounder than Adams saw.

Thus, Col. Knox set out from Lake Champlain with 59 artillery pieces, including 43 cannon; lost one eighteen-pounder; and arrived in eastern Massachusetts with the rest.

I’ve seen a report that the 59 artillery pieces Knox selected came almost evenly from Crown Point and Fort Ticonderoga. However, I haven’t found a source for that statement.

There’s also the story told in an article in the

Bulletin of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum titled “History of a Wandering Cannon.” During work on a dam across the Mohawk River in the 1850s, an iron six-pounder with the royal monogram was dredged up. It was eventually displayed at the restored Fort Ti as the cannon Knox had lost back in 1776. But I’m not sure how it shrank from being an eighteen-pounder.