When Adams Chaired the Boston Town Meeting

Before Gov. Thomas Gage shut them down, Samuel Adams and his allies used that session to authorize a delegation from the colony to the Continental Congress, as I’ve just recounted.

On the same day, there was the continuation of a town meeting in Boston. Some of that port’s merchants had started to grumble against the Whigs’ insistence that no one should pay for the tea destroyed in December (or in March, for that matter).

Adams was officially the moderator of that ongoing meeting. Expecting “a warm engagement” with the conciliatory party, Dr. Joseph Warren urged Adams to return to Boston to wield the gavel. But he was was stuck “at Salem, attending the Business of the General Court.”

At 10:00 A.M., the meeting began in Faneuil Hall. The first order of business was appointing a temporary moderator in Adams’s place. The gathering’s unanimous choice was James Bowdoin, a wealthy merchant, learned man, and genteel political leader for the Whigs.

A committee of three men went to Bowdoin’s home near Beacon Hill. He wasn’t there.

The meeting then selected merchant John Rowe to moderate. This was an unusual choice because Rowe was not a Whig stalwart. Nor was he really a Loyalist stalwart. He was a “trimmer,” adjusting his political sails according to the prevailing winds and what looked most advantageous to his business.

Perhaps the public remembered Rowe’s remark back in December about mixing tea and saltwater—the first public suggestion of that method of resolving the standoff over the East India Company cargo. Secretly Rowe appears to have regretted that remark and tried to keep a low profile afterward. So he would hardly want to chair a town meeting making controversial decisions.

In his diary Rowe wrote: “I was much engaged & therefore did not accept.” But he added a remark showing his real attitude: “The People at present seem very averse to Accommodate Matters. I think they will Repent of their Behaviour, sooner or later.”

Back at Faneuil Hall, the gathering moved on to vote for a gentleman who had never moderated the Boston town meeting before. In fact, he later said he usually kept away from town meetings. But he had represented Boston for one year in the Massachusetts General Court.

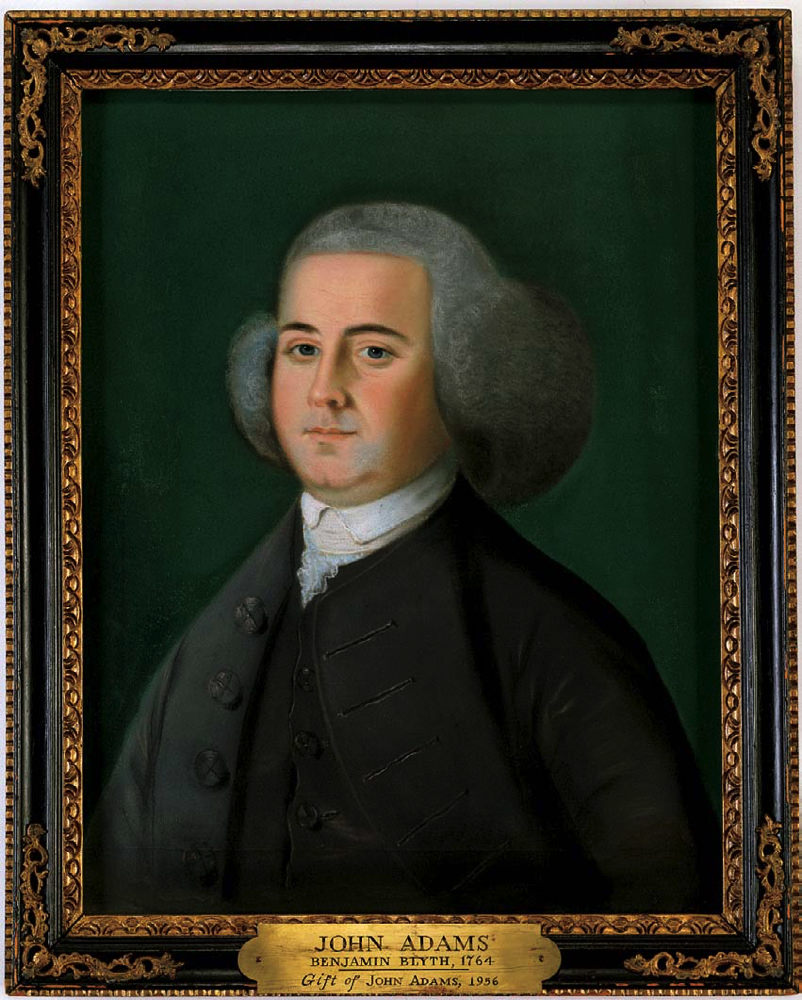

This was John Adams. Per the record, “a Committee of three Gentlemen” went to him with news of their choice, and Adams “gave his Attendance accordingly.”

TOMORROW: John Adams in the chair.