Jackson on Calhoun and Clay

One Presidential candidate’s recent suggestion of a “Second Amendment” response to losing the election prompted a Twitter discussion of Presidents threatening violence to their opponents. I noted the precedent of a reported remark from Andrew Jackson: “My only regrets are that I never shot Henry Clay or hanged John C. Calhoun.”

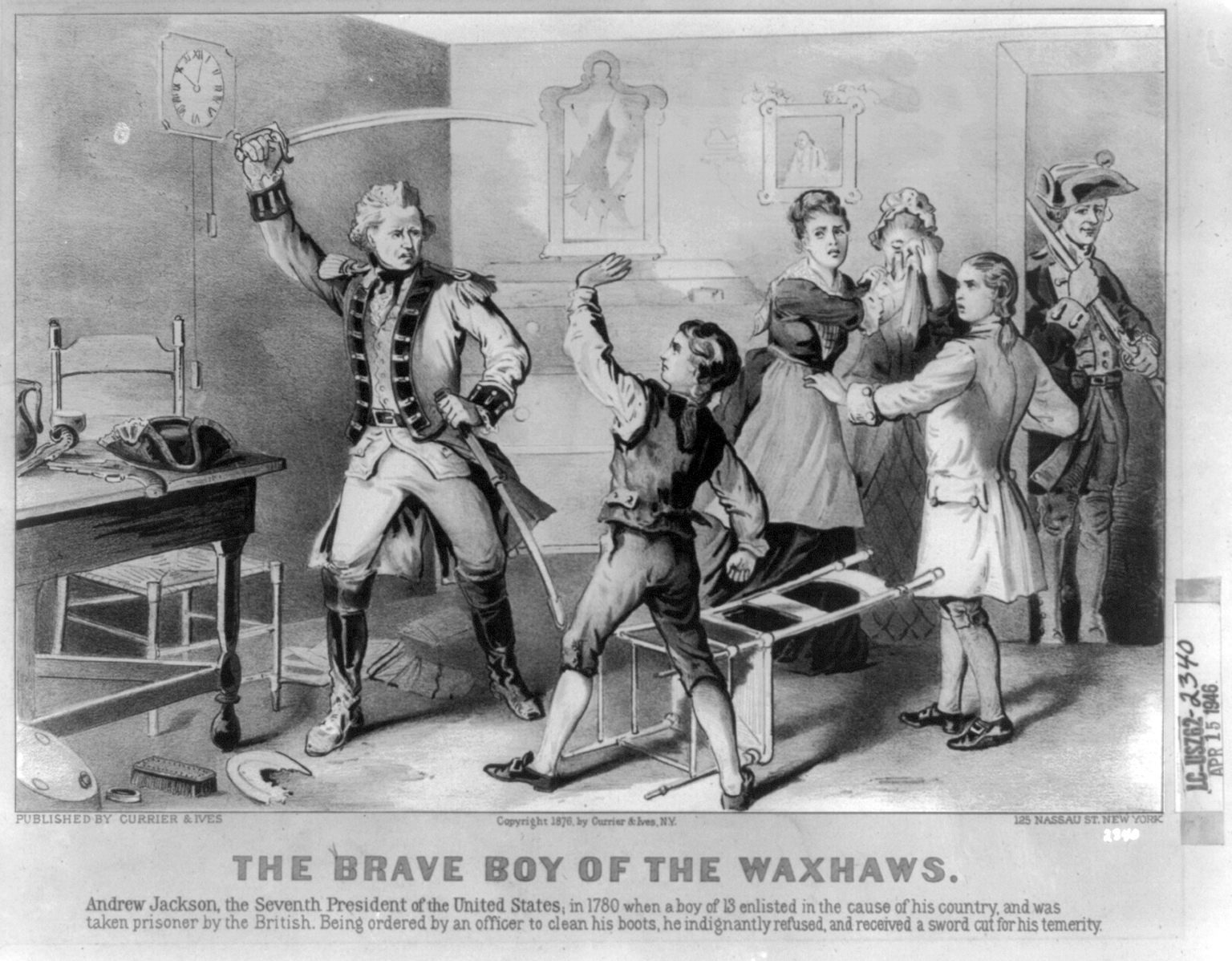

And then I realized that I was repeating a story without checking its sources, something I chide others for doing when it comes to the Revolutionary period. The Jackson administration is well past the period I research, to be sure. But as a teenager he did fight in the Revolutionary War, as shown in the print above. So I figured I could stretch a little.

The anecdote about Jackson’s regrets is quite widespread. Robert V. Remini, the leading Jackson biographer of our time, cites the story in his biography of Henry Clay. Harry Truman told it multiple times, including at a public dinner in 1951.

On the other hand, I found that authors split on when Jackson made that remark. Some say he said it on leaving the White House in 1837. Others date the statement to Jackson’s final illness in 1845. So that’s a red flag.

The earliest recounting of the remark that I could find through Google Books is an address titled “Precedents of Ex-Presidents,” delivered to the Nebraska Bar Association by George Whitelock in 1911. He said, “Old Hickory had had his drastic way, except, as he sadly lamented when departing for the Hermitage near Nashville, old, ill and in debt, that he had never got a chance to shoot Henry Clay, or to hang John C. Calhoun.” It’s notable that that’s not a direct quotation, just an expression of sentiment.

And there are some fairly authoritative sources for Jackson’s sentiment as far as Calhoun is concerned. James Parton’s three-volume biography of Jackson, published in 1860, includes this passage:

Like Parton, Poore presented Jackson’s extreme dislike of Calhoun as a matter of hanging:

That said, Parton’s 1860 Life of Andrew Jackson also includes this statement about the President’s departure from the White House:

So the part of the famous anecdote that involves shooting Clay not only doesn’t appear to have nineteenth-century backing, but there’s actually evidence that Jackson’s major regret toward Clay was not being friends.

On the other hand, we seem to be on fairly safe ground in saying that Andrew Jackson felt John C. Calhoun deserved to hang. So much so that none of the anecdotes portrays him as wanting to put Calhoun on trial first.

And then I realized that I was repeating a story without checking its sources, something I chide others for doing when it comes to the Revolutionary period. The Jackson administration is well past the period I research, to be sure. But as a teenager he did fight in the Revolutionary War, as shown in the print above. So I figured I could stretch a little.

The anecdote about Jackson’s regrets is quite widespread. Robert V. Remini, the leading Jackson biographer of our time, cites the story in his biography of Henry Clay. Harry Truman told it multiple times, including at a public dinner in 1951.

On the other hand, I found that authors split on when Jackson made that remark. Some say he said it on leaving the White House in 1837. Others date the statement to Jackson’s final illness in 1845. So that’s a red flag.

The earliest recounting of the remark that I could find through Google Books is an address titled “Precedents of Ex-Presidents,” delivered to the Nebraska Bar Association by George Whitelock in 1911. He said, “Old Hickory had had his drastic way, except, as he sadly lamented when departing for the Hermitage near Nashville, old, ill and in debt, that he had never got a chance to shoot Henry Clay, or to hang John C. Calhoun.” It’s notable that that’s not a direct quotation, just an expression of sentiment.

And there are some fairly authoritative sources for Jackson’s sentiment as far as Calhoun is concerned. James Parton’s three-volume biography of Jackson, published in 1860, includes this passage:

The old Jackson men of the inner set still speak of Mr. Calhoun in terms which show that they consider him at once the most wicked and the most despicable of American statesmen. He was a coward, conspirator, hypocrite, traitor, and fool, say they. He strove, schemed, dreamed, lived, only for the presidency; and when he despaired of reaching that office by honorable means, he sought to rise upon the ruins of his country—thinking it better to reign in South Carolina than to serve in the United States. General Jackson lived and died in this opinion. In his last sickness he declared that, in reflecting upon his administration, he chiefly regretted that he had not had John C. Calhoun executed for treason. “My country,” said the General, “would have sustained me in the act, and his fate would have been a warning to traitors in all time to come.”In 1886 the journalist Benjamin Perley Poore published Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis. Now Poore started counting those sixty years from his first visit to Washington, D.C., as a six-year-old. He didn’t enter journalism until after the Jackson administration. Nonetheless, he was a nationally known correspondent and Washington insider; indeed, Poore founded the Gridiron Club. So his stories carried weight.

Like Parton, Poore presented Jackson’s extreme dislike of Calhoun as a matter of hanging:

During the last days of General Jackson at the Hermitage, while slowly sinking under the ravages of consumption, he was one day speaking of his Administration, and with glowing interest he inquired of his physician:John Todd Edgar—a doctor of theology, not of medicine—had also been a source for Parton. He converted Jackson to Presbyterianism near the end of his life, though only after some brinksmanship involving an unbaptized child. So it looks like we’re on solid ground to say that Edgar, who was close to Jackson in his last years, told the story of the former President expressing regret for not having hanged Calhoun as a traitor.

“What act in my Administration, in your opinion, will posterity condemn with the greatest severity?”

The physician replied that he was unable to answer, that it might be the removal of the deposits.

“Oh! no,” said the General.

“Then it may be the specie circular?”

“Not at all!”

“What is it, then?”

“I can tell you,” said Jackson, rising in his bed, his eyes kindling up—“I can tell you; posterity will condemn me more because I was persuaded not to hang John C. Calhoun as a traitor than for any other act in my life.”

This was in accord with an earlier answer made by “Old Hickory,” before he had so far succumbed to disease and prior to his union with the Presbyterian Church. When his old friend and physician, Dr. Edgar, then asked him, “What would you have done with Calhoun and the other nullifiers, if they had kept on?”

“Hung them, sir, as high as Haman!” was his emphatic reply.

That said, Parton’s 1860 Life of Andrew Jackson also includes this statement about the President’s departure from the White House:

It appears to rest upon good testimony that, during his stay at Cincinnati, he expressed regret at having become estranged from Henry Clay. Clay and himself, he said, ought to have been friends, and would have been, but for the slander and cowardice of an individual whom he denominated “that Pennsylvania reptile,” and whom he said he would have “crushed,” if friends had not interceded in his behalf.For this information Parton cited, “N. Y. Evening Post, March 21st, 1859. Communication.” (I haven’t had a view at that newspaper for any more clues.)

So the part of the famous anecdote that involves shooting Clay not only doesn’t appear to have nineteenth-century backing, but there’s actually evidence that Jackson’s major regret toward Clay was not being friends.

On the other hand, we seem to be on fairly safe ground in saying that Andrew Jackson felt John C. Calhoun deserved to hang. So much so that none of the anecdotes portrays him as wanting to put Calhoun on trial first.

4 comments:

"That Pennsylvania reptile": One presumes Jackson was referring to George Kremer, who claimed authorship of the charge of a "corrupt bargain" in Clay's appointment as Secretary of State. Kremer was regarded as such a spineless nonentity that when he was revealed as the charge's author, Clay abandoned all thought of calling him out to a duel.

I tried to find any other reference to Jackson's "Pennsylvania reptile" but came up empty.

My top guess is Nicholas Biddle, president of the Bank of the U.S. With Clay's help, he fought off Jackson's attempts to close the bank, and between them they damaged the economy. There are even period cartoons showing Jackson fighting a snaky Hydra with Biddle as one of its heads.

Kremer seems like too much of a nonentity to come between Jackson and Clay, and didn't Jackson actually believe in the "corrupt bargain" argument?

I certainly disagree with most of Andrew Jackson's policies. But he may have been right about Calhoun...

I've been surprised at how swiftly Andrew Jackson's star has fallen in the last three decades. Even standing up to Calhoun doesn't seem to save him from being reckoned as a villain rather than a deeply flawed giant in American history.

Post a Comment