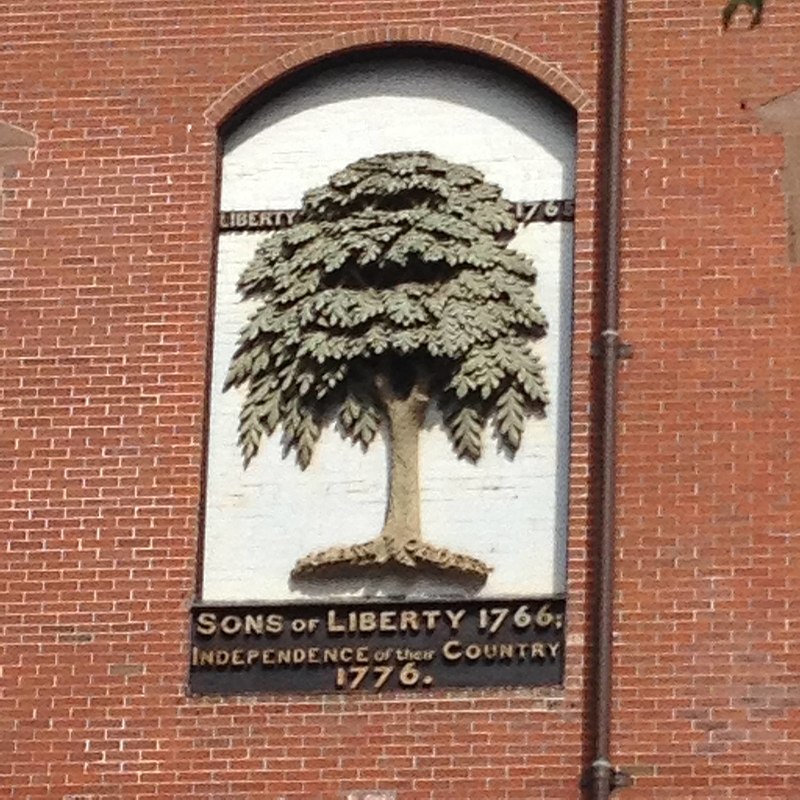

“Cheat them much as you can of ye Duties”

Under the Sugar Act of 1764, every gallon of molasses imported into British North America carried a duty of 3 pence. (There were duties on other goods as well.) Ships had to carry papers declaring how much molasses and other stuff they carried. When a crew landed cargo at a particular port, the Customs office there collected the duty and “cleared” for shipment anywhere else within the empire.

Shaw’s letters show he was constantly betting on which port would offer the best price for his molasses. The duty was the same in every port, but Shaw also did his best to minimize the tax he had to pay. And he was blatant about evading duties.

Here are samples from Shaw’s correspondence with his main trading partners showing the many tricks he and his captains used.

On 9 June 1766 to Peter Vandervoort at New York:

(…I want [Abijah] Bebee to to Land his Cargoe without Entring and Return to New Londn. and take another Cargoe of molasses on Board & Return to New York with the Same Clearance if you think it may be done, wich I leave to you) for I Cannot Clear out any more Molasses att the Custom House haveing all Ready Cleard as much as have pd. the Dutys forTwo shipments using the same certificate of duties paid.

On 14 July 1766 to Vandervoort:

I have shipt you by the bearer Abijah Bebee Ten hogsheads and Five Terses of Molasses wich is not Cleared in the Custom House and would have you do the best in Landing and Disposing of itOn 18 July 1766 to Vandervoort:

I have by the Bearer Capt. [William] Hancock shipped you as pr the Inclosed bill of Lading thirty Four Casks of Molasses wich I have Clear’d att the Custom house att about sixty Gallon. they being very large Casks I would have you dispose of them before Hancok hauls into the Dock and then have them Carried off Immediately, as I Imagine if any of the Custo. House Officers should see them they would take notice of their being very large and Possible have them Gauged Again, wich I should not Choose to have done.Underreporting the size of the casks and working fast so the authorities wouldn’t notice.

On 1 July 1767 to Thomas and Isaac Wharton of Philadelphia:

I…should have wrote you before but have been Endavoring to find what Pretentions your Collector had for obliging you to pay 1d. Sterg. pr Gallon on the Molasses after it had paid the duty in this Port, and am Inform’d by Persons who know as much about Acts of Parliment as Mr. [John] Swieft that it is not the Intention of the Act that Molasses should pay the Duty more than Once, and I should Imagine that when Mr. Swieft finds (wich is Certainly Facts) that no Other Collectr. on the Continent takes the duty but himSelf he will Repay you the money back Again on that Accott.Threatening to sue the Customs service for collecting duties twice because he cared so much about following the law. Also, not paying duties in the first place.

I shall let the matter Rest a little longer, and if I Find that he Continues to keep the Duty, I shall Imploy an Attorney to git it from him att Common Law and make no Doubt but I shall be Able to Recover it.

If Molasses should take a Rise let me know it and if I should have any Arive will order it to you without Entring of it hear.

On 5 Oct 1769 to Vandervoort:

I have also by Capt. [Edward] Tinker shipt Six hogsheads of Rum and Four Terses for Mr. John Wattles which he would have you forward as pr the Inclos’d Directions and send Ten Keggs of Brandy as I did not Choose to send any by Tinker. I hope you’l have the Terses taken out Soon as they may appear Suspicious.Unloading quickly before officials could notice.

On 14 Feb 1770 to Vandervoort:

Yesterday Capt. [Joseph] Latham arived in a Sloop of mine from Cape Francoise and I am now Loading Harris with molasses and Sugars for N Y, the Sugars shall Clear as Seads.On 14 May 1771 to the Whartons:

Inclosed is a bill of lading of 45 hhds. & 9 teirces of Melasses, and Ten hhds. of Sugar by Capt. Powers. . . . Their is only two hogsheads of Sugar cleared out, and you must get the Remainder on shore in the best manner you can. I have put 19 bags Coffee on board which is cleared out as Cocoa, you must manage that in the best manner you can.Mislabeling cargo, and getting casks “on shore in the best manner you can.”

On 17 May 1771 to the Whartons:

I have by the bearer Capt. Edwd. Tinker in the Sloop Sally, Shipt you seventy four hogsheads of Melasses, and thirteen hogsheads Sugar, which dispose of for my Accott. The Sugar is in Melasses Hogsheads & you must Land them in the Safetest manner you can, for I Could not Clear them out.11 Nov 1772 to the Whartons:

I Should have wrote you by the last Post but was att New Port on a very Disagreable Errand. A Brigg of mine from Guadalupe with Two hundred hogsheads of Melasses, by Stress of Weather was drove into New Port and the Custom House Officers Oblig’d him to Enter his Cargoe and the Stupid fellow Reported only Seventy hogsheads and they have made a Seizure of the Remainder. I have Sent a Petition to the board of Commissioners att Boston praying that it might be Admitted to an Entry. How farr they will be prevaild on, time only will Discover. In Case its Condemn’d they flatter me that I Shall have it att About Seven pence Sterling pr Gallon.Even if the Newport Customs office confiscated the 130 extra hogsheads, officials suggested that at auction he should be able to buy that molasses back at a good price.

On 2 Jan 1773 to Vandervoort:

I wrote Messrs. Whartons for a full Load for [Edward] Chappell, and I now send him with a Load of Sugars and have only Clear’d out Seventeen hogsheads and think the best plan will be for him to enter at New York and apply for Liberty to take in those twenty Casks he brought down before, and git Certificates for abought Twenty more and go on to Phila. or if you think their is no danger let him go on with his Clearance for the 17 hhds. but am really afraid of the Consiquence and think it best to Clear out some more at N York.Duplicate paperwork.

In Case Chappell cannot git up to Phila. by reason of the Ice, I would have him return to N. York, and if you can not get 48/ pr Ct. for his Sugars, I should be glad to have him Cleared out for Boston, and let him take out a new Register in his own name as I do not choose to have the Sloop go their with the old Register.

On 13 July 1774 to Vandevoort:

The bearer [Capn?] Tinker has on board about twenty thousand Gal Melasses in the Brig Mermaid wich you must dispose off on the best terms you can for my Interest. We have reported 150 hhd & 50 Teirces. I beg you will Cheat them much as you can of ye Duties.Shaw and Tinker had reported 15,000 gallons in hogsheads and another 3,300 in the smaller casks called tierces, or about 10% short of what they actually had brought in. So any way that Vandervoort could “Cheat” on the duties was added profit.

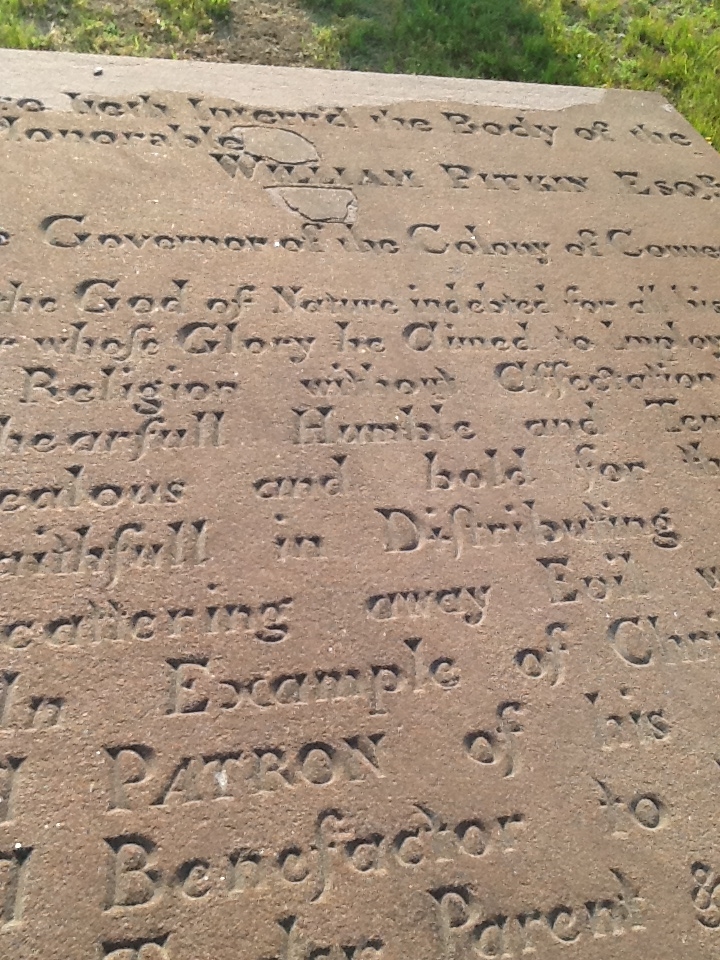

Given Shaw’s normal way of doing business, Capt. William Reid probably had good reason to be suspicious when he saw two of the merchant’s ships rendezvousing in Long Island Sound on 17 July 1769. Once Reid had seized those ships, Shaw came roaring into Newport to get them back.

It’s possible that Shaw didn’t plan to extend his repertoire of resistance to include holding Reid hostage, inciting a riot, ruining the Customs sloop, and absconding with his sloop. But that’s what he and his men and the Newport crowd ended up doing.

_(detail).jpg/220px-Edward_Hand_(NYPL_b12349196-420212)_(detail).jpg)