“This political theater stokes culture wars”

From the American Historical Association:

This hastily assembled “White House Conference on American History” took place in the Rotunda of the National Archives, although the National Archives and Records Administration had no role in organizing the program. The organizers of the event neither informed nor consulted associations of professional historians.That statement was co-signed by a long list of other historical organizations.

The American Historical Association addresses this “conference” and the president’s ill-informed observations about American history and history education reluctantly and with dismay. The event was clearly a campaign stunt, deploying the legitimating backdrop of the Rotunda, home of the nation’s founding documents, to draw distinctions between the two political parties on education policy, tie one party to civil disorder, and enable the president to explicitly attack his opponent.

Like the president’s claim at Mount Rushmore two months ago that “our children are taught in school to hate their own country,” this political theater stokes culture wars that are meant to distract Americans from other, more pressing current issues. The AHA only reluctantly gives air to such distraction; we are not interested in inflating a brouhaha that is a mere sideshow to the many perils facing our nation at this moment.

Past generations of historians participated in promoting a mythical view of the United States. Missing from this conventional narrative were essential themes that we now recognize as central to a complete understanding of our nation’s past. As scholars, we locate and evaluate evidence, which we use to craft stories about the past that are inclusive and able to withstand critical scrutiny. In the process, we engage in lively and at times heated conversations with each other about the meaning of evidence and ways to interpret it. As teachers, we encourage our students to question conventional wisdom as well as their own assumptions, but always with an emphasis on evidence.

It is not appropriate for us to censor ourselves or our students when it comes to discussing past events and developments. To purge history of its unsavory elements and full complexity would be a disservice to history as a discipline and the nation, and in the process would render a rich, fascinating story dull and uninspiring.

The AHA deplores the use of history and history education at all grade levels and other contexts to divide the American people, rather than use our discipline to heal the divisions that are central to our heritage. Healing those divisions requires an understanding of history and an appreciation for the persistent struggles of Americans to hold the nation accountable for falling short of its lofty ideals. To learn from our history we must confront it, understand it in all its messy complexity, and take responsibility as much for our failures as our accomplishments.

From the Organization of American Historians:

In his September 17, 2020, speech at the National Archives on history education, President Trump railed against “Critical race theory, the 1619 Project, and the crusade against American history,” which he characterized as “toxic propaganda, ideological poison that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together. It will destroy our country.” Coming at the end of the White House Conference on American History—a hastily-arranged gathering, organized without input or participation from historical associations and including panelists who are not experts in the field—the remarks are only the most recent example of the Trump administration’s misguided and dangerous attempts to politicize the teaching and writing of United States history.As Donald Trump’s lack of previous public service, suspicious tax schemes, exploitation of charities, comments on fellow citizens, and depraved indifference in face of an epidemic show, he’s not actually patriotic. Likewise, his invention of a Civil War battle and his error-riddled descriptions of the past show that he’s not actually interested in American history.

As the largest professional organization in the country representing historians of U.S. history, the Organization of American Historians opposes the biased views and mischaracterizations of historical inquiry and education expressed in these statements. Further, the OAH rejects the narrow and celebratory “1776 Project” put forward in this speech as a partisan ploy meant to restrict historical pedagogy, stifle deliberative discussion, and take us back to an earlier era characterized by a limited vision of the U.S. past.

History is not and cannot be simply celebratory. Vibrant democratic societies are not built upon a foundation of selective depictions of the past, but rather demand critical examination of and grappling with the historical record. The best historical inquiry acknowledges and interrogates systems of oppression—racial, ethnic, gender, class—and openly addresses the myriad injustices that these systems have perpetuated through the past and into the present. We ignore such history at our peril.

The history we teach must investigate the core conflict between a nation founded on radical notions of liberty, freedom, and equality, and a nation built on slavery, exploitation, and exclusion. The 1619 Project’s approach to understanding the American past and connecting it to newly urgent movements for racial justice and systemic reform point to this conflict, and to the ways in which slavery and racial injustice have and continue to profoundly shape our nation. Critical race theory provides a lens through which we can examine and understand systemic racism and its many consequences. It does not introduce the “twisted web of lies in our schools and classrooms” of the President’s telling, but rather illustrates the wide gap between the ideal and reality of opportunity in our shared past, as well as long-unfulfilled promises and possibilities.

The Organization of American Historians remains dedicated to promoting excellence in the scholarship, teaching and presentation of American history, and to encouraging informed public discussion of and engagement with historical questions that are critical to understanding both the triumphs and tragedies of our nation’s past. It is only through purposeful interrogations of our national story that we can appreciate the history of the United States in its full complexity and utilize our knowledge of it to inform our present and build a better future.

Trump wants only what benefits himself and his ego (not necessarily in that order). He tried to gin up this controversy over teaching U.S. history merely for his political advantage, in hopes of once again eking out a majority in the Electoral College.

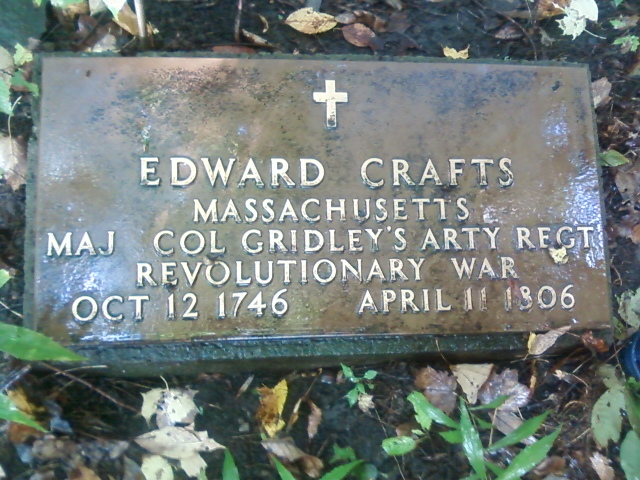

(Shown above: The portion of Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence that states, “to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”)