Jacob Bailey Meets Charles Paxton’s “Gay Order”

Jacob Bailey (1731-1808) graduated from Harvard College in 1755, ranked at the bottom of his class in social rank. He chose to go into the ministry, starting as a Congregationalist like most of his fellow New Englanders.

Shortly after receiving his master’s degree in 1758, however, Bailey decided to become an Anglican minister. That required going to England to meet with a bishop for ordination. In his diary he wrote:

Twelfth Night, 6 Jan 1760, was a Sunday. The Congregationalist meetinghouses had their regular services, but the Anglican churches made a bigger deal of the holiday. Bailey apparently attended King’s Chapel and visited briefly with the rector, the Rev. Henry Caner. Then he made a more unusual social call:

Charles Paxton was in fact a lifelong bachelor. The Whig press ridiculed his elaborate courtly manners and sneered that he was frightened of boys’ games and once concealed himself in women’s clothing.

Christopher (Kit) Minot also never married. Born in 1706 and graduating from Harvard in 1725, he eventually joined the Customs service, serving as a land waiter. Hannah Mather Crocker later wrote that Minot was “a man of keen wit” who “moved in the first circles.” He left Boston during the 1776 evacuation and died in Halifax in March 1783.

I’m not sure of the identities of the other men Bailey named, but they might also be connected to the Customs service. William McKenzie was a searcher for the Customs office in Savannah in the late 1760s. Stuart might have been Duncan Stewart (1732-1793), later Customs collector in New London, Connecticut; Stuart married a daughter of Boston merchant John Erving in 1767, and they had ten children.

Likewise, Jacob Bailey eventually married and had six children. I didn’t find in his modern biography any further indication of interest in other men. But just four days later as he rode out of Boston, he wrote: “In the boat’s crew I discovered a young man, whose appearance and behavior pleased me more than all I had seen.” Here he was, just trying to sail away to be ordained, and attractive young men kept throwing themselves in front of him.

Okay, “gay” didn’t acquire its sexual definition until the twentieth century, and our understanding of homosexuality is also different from that of 1760. When Bailey wrote about gentlemen “chiefly upon the gay order,” he probably meant an upper-class, non-Calvinist, luxury-enjoying lifestyle. Bailey’s relatively poor, rural family descended from New England Puritans was mostly likely awash with suspicions about wealthy Anglicans. What sort of society was he getting himself into as he changed denominations? But the young minister was pleased to find a set of gentlemen sharing a decorous Twelfth Night conversation—and he could relax.

Of course, there might well have been gay men in that parlor.

Shortly after receiving his master’s degree in 1758, however, Bailey decided to become an Anglican minister. That required going to England to meet with a bishop for ordination. In his diary he wrote:

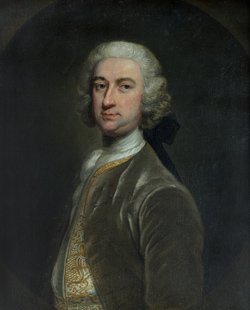

I visited my parents, where I found my Aunt Bailey, who all cried out upon me when I discovered my resolutions of visiting London for orders; and after all, I found it extremely difficult, with all the arguments I could use, to gain them over to any favorable sentiments concerning the Church of England.Bailey didn’t set out on his journey until late 1759, traveling first to Boston to arrange passage. He met with Charles Paxton (shown here), a Customs officer and warden of King’s Chapel, on 26 December. The young man wrote in his diary that Paxton promised “to use his interest with the commander of the Hind in my behalf, for a passage to England.”

Twelfth Night, 6 Jan 1760, was a Sunday. The Congregationalist meetinghouses had their regular services, but the Anglican churches made a bigger deal of the holiday. Bailey apparently attended King’s Chapel and visited briefly with the rector, the Rev. Henry Caner. Then he made a more unusual social call:

…having received an invitation from Mr. Paxon, I waited upon him, was politely received, introduced into a fine parlor among several agreeable gentlemen. I found here the famous Kit Minot, Mr. McKensie, and one Mr. Stuart, a pretty young gentleman.Let’s imagine reading those same words from a mid-20th-century author: a gathering of men, most “upon the gay order” and one “a pretty young gentleman.” The writer is obviously concerned about the conversation not being “modest and perfectly innocent.” But he comes away feeling he’s never been “in any company where I could behave with greater freedom.” We’d easily interpret that as the account of a homosexual man meeting other out-homosexual men for the first time.

I observed that our company, though chiefly upon the gay order, distinguished the day by a kind of reverent decorum. Our conversation was modest and perfectly innocent, and I scarce remember my ever being in any company where I could behave with greater freedom.

Charles Paxton was in fact a lifelong bachelor. The Whig press ridiculed his elaborate courtly manners and sneered that he was frightened of boys’ games and once concealed himself in women’s clothing.

Christopher (Kit) Minot also never married. Born in 1706 and graduating from Harvard in 1725, he eventually joined the Customs service, serving as a land waiter. Hannah Mather Crocker later wrote that Minot was “a man of keen wit” who “moved in the first circles.” He left Boston during the 1776 evacuation and died in Halifax in March 1783.

I’m not sure of the identities of the other men Bailey named, but they might also be connected to the Customs service. William McKenzie was a searcher for the Customs office in Savannah in the late 1760s. Stuart might have been Duncan Stewart (1732-1793), later Customs collector in New London, Connecticut; Stuart married a daughter of Boston merchant John Erving in 1767, and they had ten children.

Likewise, Jacob Bailey eventually married and had six children. I didn’t find in his modern biography any further indication of interest in other men. But just four days later as he rode out of Boston, he wrote: “In the boat’s crew I discovered a young man, whose appearance and behavior pleased me more than all I had seen.” Here he was, just trying to sail away to be ordained, and attractive young men kept throwing themselves in front of him.

Okay, “gay” didn’t acquire its sexual definition until the twentieth century, and our understanding of homosexuality is also different from that of 1760. When Bailey wrote about gentlemen “chiefly upon the gay order,” he probably meant an upper-class, non-Calvinist, luxury-enjoying lifestyle. Bailey’s relatively poor, rural family descended from New England Puritans was mostly likely awash with suspicions about wealthy Anglicans. What sort of society was he getting himself into as he changed denominations? But the young minister was pleased to find a set of gentlemen sharing a decorous Twelfth Night conversation—and he could relax.

Of course, there might well have been gay men in that parlor.

No comments:

Post a Comment