“Revolutionary Harbor” Discussion, 17 Feb.

On Wednesday, 17 February, the National Parks of Boston and Boston Harbor Now will host an online discussion on “Revolutionary Harbor: The Transatlantic World of Peter Faneuil,” about the role of slavery in shaping Boston’s eighteenth-century economy.

Peter Faneuil was one of the town’s richest merchants in the first half of that century, honored for giving money that went to building the earliest version of Faneuil Hall.

Much of Faneuil’s inheritance and business was rooted in chattel slavery, either from supplying the sugar-producing slave-labor camps of the Caribbean or from bringing more kidnapped African people to the New World. In that, he wasn’t unusual among leading New England merchants; his family was simply wealthier than most.

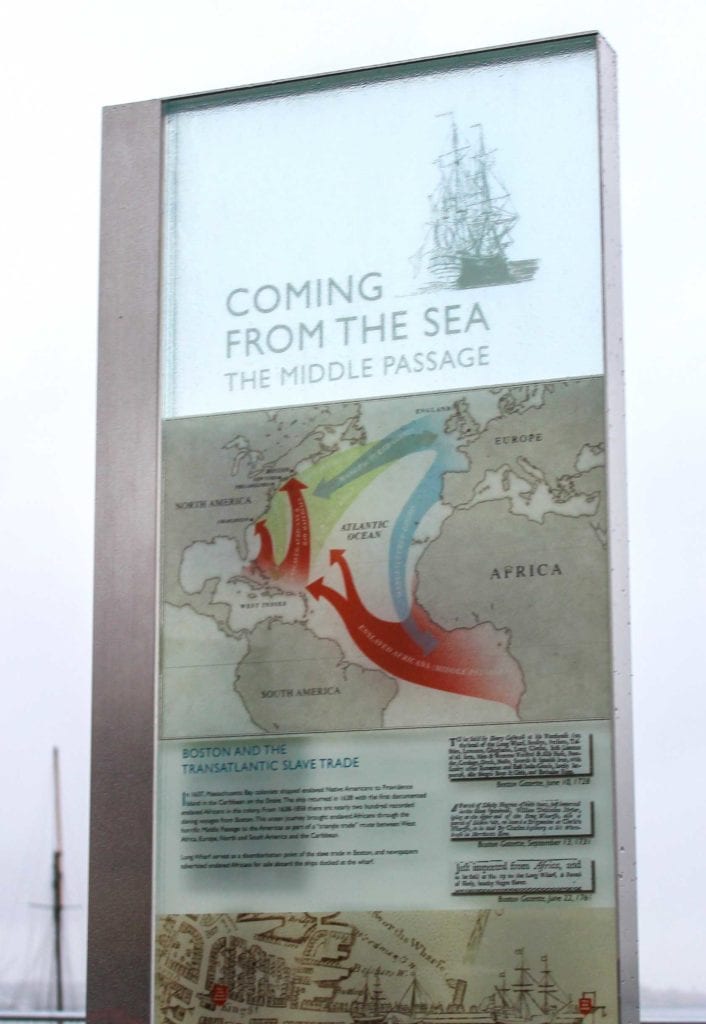

Last October, the National Parks of Boston, the city of Boston, the Museum of African American History, and the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project installed a marker at the end of Long Wharf recognizing Boston’s participation in the transatlantic slave trade.

One side, headed “Coming from the Sea,” describes the trade in people in and out of Boston harbor. The other side, which one sees while facing the city, spotlights Crispus Attucks, Phillis Wheatley, Prince Hall, and Paul Cuffee as notable New Englanders of African descent.

It doesn’t look like Peter Faneuil’s name is on that marker, nor the name of any other individual slave trader or slave-camp supplier. Ironically, then, those merchants appear as a faceless mass—precisely what slavery and many decades of historiography reduced the captive Africans to. But in this case, anonymity might erase those men’s individual choices to participate in that trade.

Faneuil’s name remains, of course, on Faneuil Hall, nicknamed the “Cradle of Liberty,” which some people a paradox. I discussed the potentials of renaming that building last September.

This discussion diving deeper into Peter Faneuil’s mercantile world is due to start on Wednesday at 7:00 P.M. and to run until 8:15. Register in advance here.

Peter Faneuil was one of the town’s richest merchants in the first half of that century, honored for giving money that went to building the earliest version of Faneuil Hall.

Much of Faneuil’s inheritance and business was rooted in chattel slavery, either from supplying the sugar-producing slave-labor camps of the Caribbean or from bringing more kidnapped African people to the New World. In that, he wasn’t unusual among leading New England merchants; his family was simply wealthier than most.

Last October, the National Parks of Boston, the city of Boston, the Museum of African American History, and the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project installed a marker at the end of Long Wharf recognizing Boston’s participation in the transatlantic slave trade.

One side, headed “Coming from the Sea,” describes the trade in people in and out of Boston harbor. The other side, which one sees while facing the city, spotlights Crispus Attucks, Phillis Wheatley, Prince Hall, and Paul Cuffee as notable New Englanders of African descent.

It doesn’t look like Peter Faneuil’s name is on that marker, nor the name of any other individual slave trader or slave-camp supplier. Ironically, then, those merchants appear as a faceless mass—precisely what slavery and many decades of historiography reduced the captive Africans to. But in this case, anonymity might erase those men’s individual choices to participate in that trade.

Faneuil’s name remains, of course, on Faneuil Hall, nicknamed the “Cradle of Liberty,” which some people a paradox. I discussed the potentials of renaming that building last September.

This discussion diving deeper into Peter Faneuil’s mercantile world is due to start on Wednesday at 7:00 P.M. and to run until 8:15. Register in advance here.

No comments:

Post a Comment