What Ukawsaw Gronniosaw’s Book Had to Say

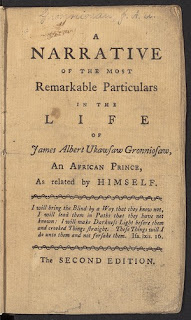

Among the digitized items in the Harvard Libraries’ Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom collection that I mentioned yesterday is A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as related by himself.

Published in Bath, England, in 1770, this was the first autobiography of a black former slave published in English, and one of the first handful of English books of any kind by a black author.

Interestingly, Gronniosaw was literate only in Dutch, having learned to read while enslaved in New York early in the century. His story was taken down by “a young lady of the town of Leominster.”

Gronniosaw dedicated his memoir to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, the same evangelical noblewoman who financed the publication of Phillis Wheatley’s first book of poems. Gronniosaw also composed a letter to the countess thanking her for financial support a couple of years later—the only other known sample of his words.

Harvard’s copy of this book is labeled the second edition, but it doesn’t state where and when it was printed. (Sen. Charles Sumner, champion of abolition and civil rights, bequeathed this copy to the university.) The first American edition was published in Newport by Solomon Southwick in 1774. The Harvard library also owns a copy of a Welsh translation published in 1779, and there were several more editions in the decades that followed, showing the book’s popularity.

One notable aspect of Gronniosaw’s story is his description of how he first understood reading when he saw a white sea captain doing it—he thought that the book was talking to that man but wouldn’t talk to him as well. Henry Louis Gates traced this “Talking Book” trope through several more slave narratives in his study The Signifying Monkey. (Gates also included Gronniosaw’s text in Pioneers of the Black Atlantic, summarizing his earlier analysis in the introduction.)

Gronniosaw depicted himself as a prince in his birthplace, Bornu, at least by his maternal ancestry. He also said he was a dissenting monotheist among pagans. Gates therefore connects Gronniosaw’s description of himself to the idea of the Noble Savage, already established in British literature.

After being captured and sold into slavery in his teens, Gronniosaw recounted, he was shipped to Barbados, then New York, where he converted to Christianity and learned to read. Freed by his clerical master’s will, he signed onto a privateer and later into the 28th Regiment of Foot, but his goal was to reach England.

Once there, Gronniosaw struggled as a poor laborer. He married a widowed weaver, and they moved from one city to another during the 1760s and early 1770s, raising their children. In Kinderminster, Gronniosaw connected with a Dissenting minister who knew the Countess of Huntingdon, and that led to his life story being published.

Unlike other African-born memoirists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Gronniosaw did not condemn slavery. He did condemn racism, but seemed to feel that he deserved equal treatment in Britain because he was a Christian, not because he was a person.

For many decades Gronniosaw’s book was the only evidence of his life. Then scholars discovered a death notice in the Chester Chronicle dated 2 Oct 1775 and a line in the burial register for that city’s church of St. Oswald. The newspaper repeated the book’s information about Gronniosaw, including both his Christian and original African names, and both sources said he had died at the age of seventy.

Published in Bath, England, in 1770, this was the first autobiography of a black former slave published in English, and one of the first handful of English books of any kind by a black author.

Interestingly, Gronniosaw was literate only in Dutch, having learned to read while enslaved in New York early in the century. His story was taken down by “a young lady of the town of Leominster.”

Gronniosaw dedicated his memoir to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, the same evangelical noblewoman who financed the publication of Phillis Wheatley’s first book of poems. Gronniosaw also composed a letter to the countess thanking her for financial support a couple of years later—the only other known sample of his words.

Harvard’s copy of this book is labeled the second edition, but it doesn’t state where and when it was printed. (Sen. Charles Sumner, champion of abolition and civil rights, bequeathed this copy to the university.) The first American edition was published in Newport by Solomon Southwick in 1774. The Harvard library also owns a copy of a Welsh translation published in 1779, and there were several more editions in the decades that followed, showing the book’s popularity.

One notable aspect of Gronniosaw’s story is his description of how he first understood reading when he saw a white sea captain doing it—he thought that the book was talking to that man but wouldn’t talk to him as well. Henry Louis Gates traced this “Talking Book” trope through several more slave narratives in his study The Signifying Monkey. (Gates also included Gronniosaw’s text in Pioneers of the Black Atlantic, summarizing his earlier analysis in the introduction.)

Gronniosaw depicted himself as a prince in his birthplace, Bornu, at least by his maternal ancestry. He also said he was a dissenting monotheist among pagans. Gates therefore connects Gronniosaw’s description of himself to the idea of the Noble Savage, already established in British literature.

After being captured and sold into slavery in his teens, Gronniosaw recounted, he was shipped to Barbados, then New York, where he converted to Christianity and learned to read. Freed by his clerical master’s will, he signed onto a privateer and later into the 28th Regiment of Foot, but his goal was to reach England.

Once there, Gronniosaw struggled as a poor laborer. He married a widowed weaver, and they moved from one city to another during the 1760s and early 1770s, raising their children. In Kinderminster, Gronniosaw connected with a Dissenting minister who knew the Countess of Huntingdon, and that led to his life story being published.

Unlike other African-born memoirists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Gronniosaw did not condemn slavery. He did condemn racism, but seemed to feel that he deserved equal treatment in Britain because he was a Christian, not because he was a person.

For many decades Gronniosaw’s book was the only evidence of his life. Then scholars discovered a death notice in the Chester Chronicle dated 2 Oct 1775 and a line in the burial register for that city’s church of St. Oswald. The newspaper repeated the book’s information about Gronniosaw, including both his Christian and original African names, and both sources said he had died at the age of seventy.

No comments:

Post a Comment