“After the steed is stolen Shut the Stable Door”

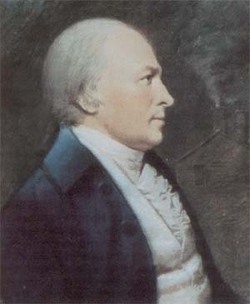

Yesterday I related, with the help of Dr. Robert A. Selig, how Samuel Talcott, Jr., sent his enslaved young man Addam off to Jeremiah Wadsworth (shown here) in Hartford.

Addam carried a letter describing how an unnamed “French general” wanted to hire or even buy him as a servant for the coming campaign. Having heard of that interest from Addam himself, Talcott asked Wadsworth to close that deal for him.

Incidentally, it turns out that was Samuel Talcott, Jr.’s second appearance on this blog. He was one of the victims of the gunpowder explosion during Hartford’s celebration of the repeal of the Stamp Act on 23 May 1766. His brother-in-law Dr. Nathaniel Ledyard was killed, and he was “very much burnt in his face and arms.”

But apparently Talcott recovered quickly enough to be back in business by the end of 1766. He appeared in Connecticut newspapers settling estates, helping to organize a new township in western Massachusetts, and otherwise acting as a respectable man of business.

We might think that experience would make Talcott more savvy than he behaved with Addam, because the next development in this story appears at the bottom of a copy of that letter he had sent off with the young man:

According to Bob Selig, “There is a letter to Wadsworth a few months later asking Wadsworth to check the Black servants of the French officers for his Addam, but Wadsworth could not find him.”

Addam may have attached himself to the French troops, but on his own terms. He may have joined the Continental Army. He may have found other work.

All we know is that Samuel Talcott, Jr., ended up with neither his slave nor any of the money he hoped to see.

I found no advertisement seeking Addam’s return, though Talcott and his father did advertise at other times in the early 1780s for a missing pocketbook, a strayed mare, and of course the repayment of debts owed them.

Evidently Talcott didn’t want Addam returned that badly. Or he didn’t want to have to explain how the young man got away.

Addam carried a letter describing how an unnamed “French general” wanted to hire or even buy him as a servant for the coming campaign. Having heard of that interest from Addam himself, Talcott asked Wadsworth to close that deal for him.

Incidentally, it turns out that was Samuel Talcott, Jr.’s second appearance on this blog. He was one of the victims of the gunpowder explosion during Hartford’s celebration of the repeal of the Stamp Act on 23 May 1766. His brother-in-law Dr. Nathaniel Ledyard was killed, and he was “very much burnt in his face and arms.”

But apparently Talcott recovered quickly enough to be back in business by the end of 1766. He appeared in Connecticut newspapers settling estates, helping to organize a new township in western Massachusetts, and otherwise acting as a respectable man of business.

We might think that experience would make Talcott more savvy than he behaved with Addam, because the next development in this story appears at the bottom of a copy of that letter he had sent off with the young man:

Dear Sr.Addam had taken advantage of his owner not expecting to see him back for a while to free himself.

The foregoing is a Coppy of Mine to you sent by my negro which I find he did not deliver and hath since disappeard——

ay—after the steed is stolen Shut the Stable Door—very true Sr—but as perhaps [smudge] another old adage—Better Late than never may be applied in this Case I trouble youagain

I am Dear Sr

ut Supra [as above] & I hope permanently

Saml. Talcott Junr.

According to Bob Selig, “There is a letter to Wadsworth a few months later asking Wadsworth to check the Black servants of the French officers for his Addam, but Wadsworth could not find him.”

Addam may have attached himself to the French troops, but on his own terms. He may have joined the Continental Army. He may have found other work.

All we know is that Samuel Talcott, Jr., ended up with neither his slave nor any of the money he hoped to see.

I found no advertisement seeking Addam’s return, though Talcott and his father did advertise at other times in the early 1780s for a missing pocketbook, a strayed mare, and of course the repayment of debts owed them.

Evidently Talcott didn’t want Addam returned that badly. Or he didn’t want to have to explain how the young man got away.

No comments:

Post a Comment