“I then gave him a genteel Basting or Caneing”

Carratook was a much smaller port, but Controller was a position of more responsibility, especially when it came to money. Malcolm had joined the service less than two years before, so that indicated the commissioners had some confidence in him.

Just below that report (in much smaller type) ran this letter:

Messieurs EDES & GILL.This newspaper item isn’t discussed in Frank W. C. Hersey’s article on Malcolm for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, or anywhere else that I can find.

Please to insert the following in your much-esteemed Paper, and you’ll oblige your humble servant, JOHN MALCOM.

WHEREAS three Officers belonging to his Majesty’s Navy us’d me very ill sometime past, by cutting Buttons from my Hussar Cloak in a private Manner, and carrying them off in their Pockets, which I resented; and on Friday the 15th Instant [i.e., of this month] I met with one of them, whose Name was Davis, two other Officers being with him—

And as said Davis had not given me Gentleman-like Satisfaction as he sundry Times promis’d, I again demanded Satisfaction of him, and he struck me with a Stick—

I then gave him a genteel Basting or Caneing, and sent him off, bidding him if he pleas’d to go and acquaint his Commodore [James Gambier] that a Boston-born Man had given him the said Davis a genteel Trimming.

JOHN MALCOM.

Boston, Feb. 1771

The confrontation Malcolm described here bears some resemblance to his more famous street fight in early 1774, particularly his insistence on being treated like a gentleman and his whaling away with his cane when that didn’t happen.

One big difference, of course, is that Malcolm’s target in 1771 was a fellow employee of the royal government, albeit in another branch. If there was any political issue in this earlier fight, it was his suspicion that British officers looked down on him as a “Boston-born” colonial.

At this time, Malcolm aligned himself with the town—the same town that would attack him brutally a few years later. He was even using the Boston Whigs’ principal newspaper to promulgate that message.

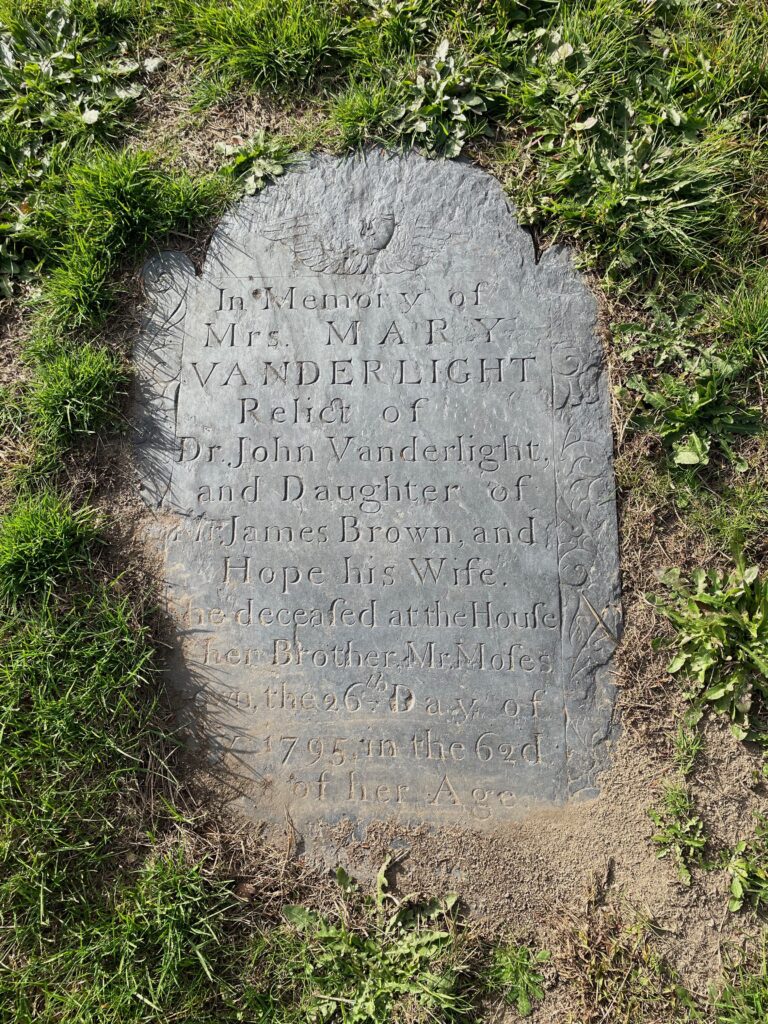

[My photo above shows a “fist cane” that belonged to Thomas Hancock and was on display at the Massachusetts Historical Society five years ago.]