The Short Military Career of Lt. Col. Thomas Williams, Jr.

The Journal of the American Revolution just published Tim Abbott’s article about Lt. Col. Thomas Williams, Jr. (1746–1776), of Stockbridge.

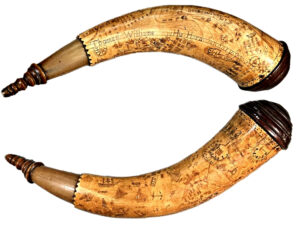

Williams left behind an engraved powder horn, now in the collection of the Stockbridge Library Museum and Archives. It shows Boston landmarks.

(This is different from the Dr. Thomas Williams powder horn recorded by Rufus Alexander Grider in 1888 and now lost.)

The siege lines around Boston contained some professional horn carvers selling their work to men who wanted souvenirs of military service. I suspect the Williams horn is one like that. As an officer and as a lawyer in civilian life, he probably didn’t have the time or inclination to do his own carving.

As Abbott’s article recounts, Williams was one of two minute company captains who responded to the Lexington Alarm from Stockbridge. The other company included a score of men from the town’s Native community and thus gets more attention.

As the troops besieging Boston organized themselves into an army enlisted through the end of the year rather than an emergency militia force, Williams became part of Col. John Paterson’s regiment. In September he volunteered for Col. Benedict Arnold’s expedition through Maine to Québec.

However, Williams was in the rear guard led by Lt. Col. Roger Enos (1729–1808), who in late October decided to turn back. That was controversial. Enos was tried and acquitted in a court-martial. He was probably lucky to go through that procedure before the army at Cambridge received “Colonel Arnolds evidence,” as Gen. George Washington reported.

Williams left Paterson’s regiment at the end of 1775, but on 9 Jan 1776 he became lieutenant colonel of a new regiment under Col. Elisha Porter to be sent up to Québec along Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River. This time Williams made it to the outskirts of the city, but smallpox was weakening the Continental forces.

Those Americans were trying to inoculate and fight the war at the same time. Abbott writes:

Williams doesn’t appear to have left behind his own diary or letters—his powder horn might have been his only personal record of military service, and it probably wasn’t his own creation. Abbott has therefore done the work of reconstructing his career by weaving together official records and other officers’ accounts.

Williams left behind an engraved powder horn, now in the collection of the Stockbridge Library Museum and Archives. It shows Boston landmarks.

(This is different from the Dr. Thomas Williams powder horn recorded by Rufus Alexander Grider in 1888 and now lost.)

The siege lines around Boston contained some professional horn carvers selling their work to men who wanted souvenirs of military service. I suspect the Williams horn is one like that. As an officer and as a lawyer in civilian life, he probably didn’t have the time or inclination to do his own carving.

As Abbott’s article recounts, Williams was one of two minute company captains who responded to the Lexington Alarm from Stockbridge. The other company included a score of men from the town’s Native community and thus gets more attention.

As the troops besieging Boston organized themselves into an army enlisted through the end of the year rather than an emergency militia force, Williams became part of Col. John Paterson’s regiment. In September he volunteered for Col. Benedict Arnold’s expedition through Maine to Québec.

However, Williams was in the rear guard led by Lt. Col. Roger Enos (1729–1808), who in late October decided to turn back. That was controversial. Enos was tried and acquitted in a court-martial. He was probably lucky to go through that procedure before the army at Cambridge received “Colonel Arnolds evidence,” as Gen. George Washington reported.

Williams left Paterson’s regiment at the end of 1775, but on 9 Jan 1776 he became lieutenant colonel of a new regiment under Col. Elisha Porter to be sent up to Québec along Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River. This time Williams made it to the outskirts of the city, but smallpox was weakening the Continental forces.

Those Americans were trying to inoculate and fight the war at the same time. Abbott writes:

The timing for the deliberate exposure of Porter’s Regiment to smallpox could not have been worse. The inoculation process required effective quarantine for three to four weeks, during which the men were both weak and contagious. Even for those under treatment, severe cases could still develop and mortality rates under the best conditions still ran 1 to 2 percent. Porter’s men had no more than three days in hospital after they were inoculated before the siege was dramatically lifted by the arrival of a British fleet on May 6 and the American forces were soon driven back upriver in full retreat. Not only were they exposed to physical stress while they developed smallpox symptoms, but they became a significant vector for the spread of the disease to others in its more deadly form.The American commander, Gen. John Thomas, died on 2 June. Lt. Col. Williams led his men back to Crown Point, New York, before falling ill. He didn’t make it home to Stockbridge.

Williams doesn’t appear to have left behind his own diary or letters—his powder horn might have been his only personal record of military service, and it probably wasn’t his own creation. Abbott has therefore done the work of reconstructing his career by weaving together official records and other officers’ accounts.

No comments:

Post a Comment