Philip Mortimer, from Waterford to Boston to Middletown

James Mortimer (c. 1704–1773) was a tallow chandler. On 16 Aug 1741 at King’s Chapel he married another arrival from Waterford: Hannah Alderchurch, twelve years his senior.

James Mortimer advertised “Good Dipp’d Tallow CANDLES” and “the best of IRISH BUTTER by the Firkin” from his shop near Clark’s Wharf, later Hancock’s Wharf. He prospered enough that by the 1760s he owned at least one enslaved worker, named Yarrow, and Apple Island in Boston harbor.

Peter Mortimer (c. 1715–1773) was a ship’s captain.

The middle of these three brothers, Philip Mortimer (c. 1710–1794), was a ropemaker. He married Martha Blin (1716–1773) on 14 Nov 1742, also at King’s Chapel. Though she was said to be “of Boston,” she came from a Wethersfield, Connecticut, family.

Philip Mortimer had a higher profile than his brothers. He was in Boston by 1735, when he witnessed a deed. Two years later, he was one of the founders of the Charitable Irish Society. On 17 Oct 1738 Philip Mortimer shared an advertisement with two other ropemakers, each seeking the return of a teen-aged indentured servant.

On 11 Aug 1740, the Boston Gazette carried this notice:

Just Imported and to be Sold by Edward Alderchurch and Philip Mortimer, on board the Schooner Two Friends, Thomas Carnell Master, now lying at the Long Wharfe near the upper Crane, Choice Welch Coal, a Parcel of likely Boys and Girls; good Rice, Virginia Pork, good Cordage, Cod-Lines and Twine, all at a very reasonable Rate, for ready Money.A year later a similar ad appeared in the Boston Evening-Post, this one adding that the “likely Boys and Girls” were “fit for Town or Country; the Girls can spin fine Thread, and do any sort of Houshold Work.” They were evidently more indentured youths from Ireland.

By 1749, according to the American-Irish Historical Society’s Recorder in 1901, Philip and Martha Mortimer had moved from Boston to Middletown, Connecticut. As the name implies, that was an inland town, halfway between the towns of Hartford and Wethersfield and the Connecticut River’s mouth at Saybrook. Nonetheless, Middletown had small shipyards, and Philip Mortimer saw the potential to build a ropewalk running perpendicular off the main street.

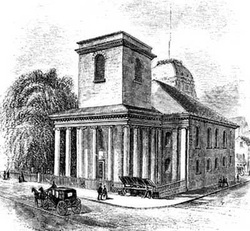

Mortimer quickly became a big fish in that small pond: town official, militia captain, Anglican church warden, Freemason. He owned the grandest house in town, shown above.

Eventually Philip Mortimer also owned an enslaved rope spinner named Prince. If the man later known as Prince Mortimer was indeed born in 1724, as calculated from his reported age when he died, and brought to Connecticut as a child, then he was in his late twenties and had been worked in Middletown for almost two decades before Philip Mortimer arrived. On the other hand, if Prince Mortimer was born later, then he could have arrived at the ropewalk as a child or teenager, fresh from being kidnapped and transported across the Atlantic, and immediately put into training to make rope.

COMING UP: Deaths and marriages.