A Firmer for Molding Your Square Butts

I looked up a bunch of those terms while confirming my transcription and got curious about others. So here’s what I learned about the unfamiliar inventory at the Brazen Head.

close-stool pans: Close stools were cabinets with chamber pots inside.

coffin bullions: Lumps of metal used to decorate coffins, it looks like.

double and single spring chest locks, stock locks: Edward Hoppus’s Builder’s Dictionary said, “LOCKS for Doors are of various Kinds; as for outer Doors, called Stock-locks; for Chamber-doors, call’d Spring-locks, &c.”

egg nob locks: Apparently locks built with doorknobs shaped like eggs.

H & HL hinges: Door hinges distinguished by their shapes. H hinges looked like the letter H. HL hinges, as illustrated a couple of days ago, looked like an H mashed with an L; some professional guides therefore called them IL hinges instead.

firmers: Merriam-Webster says a “firmer chisel” is “a woodworking chisel with a thin flat blade,” and dates the two-word phrase to 1827. The Jacksons’ ad is considerably earlier, of course. The word comes from the French “fermoir,” meaning to form.

gimblets: Now spelled “gimlet,” a T-shaped tool with a screw-tip for boring holes.

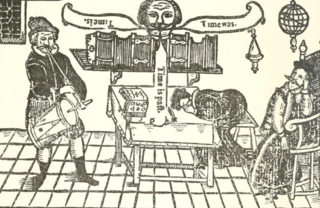

hallow and rounds: The first type often spelled “hollow,” these are planes for molding wood, shown here.

splinter and black pad-locks: A splinter padlock had four springs, according to a nineteenth-century reference. A black padlock was presumably black.

post pepper-mills: The sort of cylindrical pepper grinder we’re used to.

handles & scutcheons: Scutcheons were small metal plates, often shaped like shields (escutcheons), to protect part of a wooden surface from handling.

prospect hinges: These seem to be hinges for the “prospect door” in a desk, which was a “single, hinged portal fashioned with a keyhole,…for private or secret documents.”

brass & iron table ketches: Even Luke Beckerdite’s American Furniture could only guess that a “table Ketch” was “possibly a tea table,” but it sounds like it was part of a table—maybe a metal reinforcement of a table leg or foot.

rule joint table hinges: Diagram of a rule joint for a table leaf here.

square butts, dovetails: I think these were metal pieces to reinforce types of joints for two pieces of wood.

girt web: Usually called “girth web,” heavy canvas straps used to strap on saddles and other things.

jobents: A specialty nail with a thick shank, made for attaching iron straps.

dutch spectacles: Spectacles that perched on one’s nose without earpieces, like pince-nez.

bath metal thimbles with steel tops: Bath metal was an alloy of zinc and copper.

aul-hafts: Handles for awls.

spinnel: Sometimes this is a term for a mineral, more usually spelled “spinel.” The phrase “short spinel” is defined as “bleached yarn” or “unwrought inkle” in nineteenth-century references. But I can’t figure out why the Jacksons would be selling either of those things, and why they would list it between “punches” and “white wax.”

Box Irons, Flat Irons: Flat irons were solid, and box irons had a metal part that could be removed and placed in the fire, then replaced in the hollow of the iron to keep it heated.

And finally…

A Quantity of large brown Paper fit for sheathing Ships: In the 1730s, there were two ways to protect ships’ hulls against shipworm. One was attaching sheets of lead to the hull, which of course didn’t help with buoyancy. The other was to plaster the hull with tar, stick on a layer of hair, and then attach a thin sheath of wood that could be replaced as it was eaten away. It looks like thick rag paper could substitute for or supplement the hair.

(When copper sheathing became standard in the late eighteenth century, paper was one way to keep different metals from touching each other in the salt water and suffering galvanic corrosion. But Mary Jackson’s 1736 ad was too early to refer to that use.)

TOMORROW: Historical context for The Saga of the Brazen Head so far.