Israel Putnam and ”an express from Boston”

On 1 Sept 1774, British soldiers acting on orders of Gen. Thomas Gage took control of province-owned gunpowder stored in Charlestown (now Somerville) and two cannon used by a Cambridge militia company.

On 1 Sept 1774, British soldiers acting on orders of Gen. Thomas Gage took control of province-owned gunpowder stored in Charlestown (now Somerville) and two cannon used by a Cambridge militia company.

As governor and thus captain-general of the Massachusetts militia, Gage had the authority to issue that order. But coming on top of the Massachusetts Government Act the previous month, the move looked to local white men like another step toward depriving them of their traditional rights.

That evening there were some disturbances in Cambridge outside the house of William Brattle, the militia general who had prompted Gage’s move, and Jonathan Sewall, the royal attorney general. But eventually everyone went home, especially after Esther Sewall treated the crowd around her home to a round of drinks.

News of the event still spread, and the farther it got from Cambridge, the more dire it became. People were hearing there had been a second Massacre, or worse. The outer towns in Middlesex County were alarmed enough to send thousands of militiamen streaming into Cambridge the next day—a confrontation that historians later dubbed the “Powder Alarm.” (The first two chapters of The Road to Concord describe those two days in September 1774, which I argue is when Massachusetts’s resistance turned into revolution.)

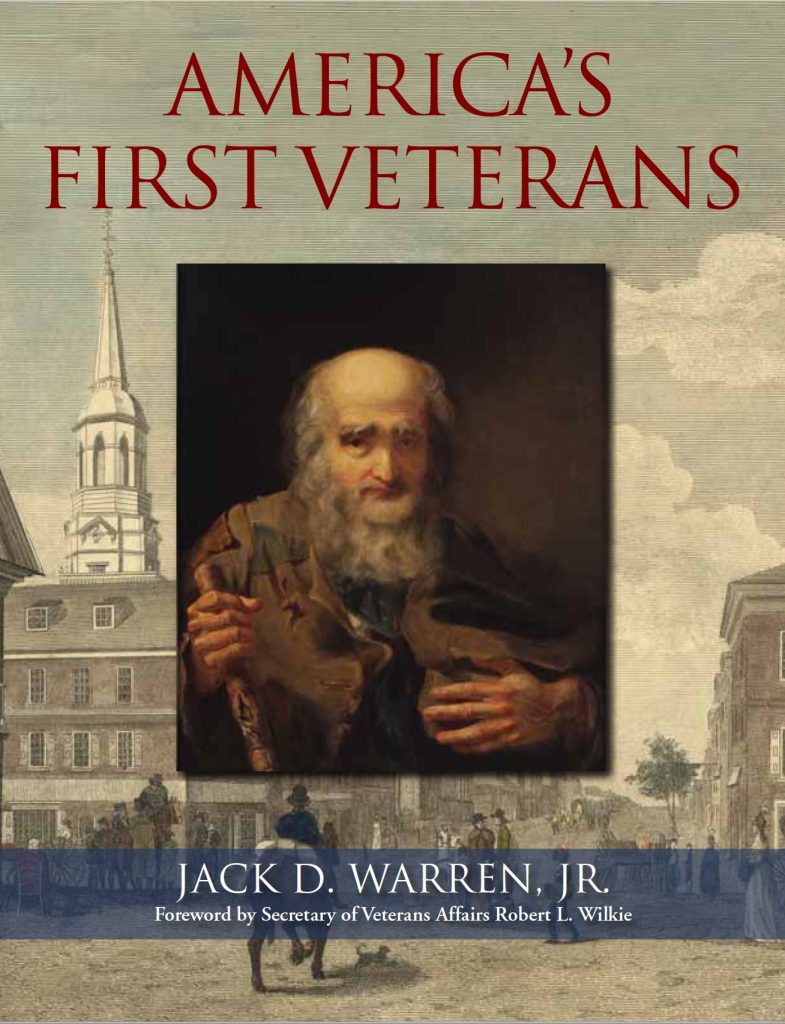

Though there was still no violence in Cambridge, the rumors from 1 September continued to spread faster than that corrective good news. The alarm reached Israel Putnam (shown above) in Pomfret, Connecticut, in the late morning of Saturday, 3 September.

Putnam had extensive military experience in the Seven Years’ War, both with Rogers’ Rangers in the west and on the 1762 expedition to Cuba. He ranked as a colonel in the Connecticut militia. And on 3 September he saw his job as mobilizing that militia to help Massachusetts.

Putnam sent letters to men in other part of Connecticut, and he dashed off a special note to his neighbor Godfrey Malbone. We met Malbone last year in connection with the Anglican church he built in his largely Congregationalist corner of Connecticut.

Malbone had also reached the rank of colonel in the militia, mostly on the basis of his wealth. But he didn’t come from an old New England family, he’d spent some years at the University of Oxford, and he didn’t much care for his Yankee neighbors.

According to the Connecticut Historical Society, Putnam wrote to Malbone:

Saturday, 12 p.m.Malbone’s reply was short:

Dear Sir. I have this minute had an express from Boston that the fight between Boston and Regulars [began] last night at sunset, the cannon began to and continued playing all night, and they beg for help,—and don’t you think it is time to go?

I am, Sir, your most obedient servant,

Israel Putnam

Go to the devilTOMORROW: Connecticut on the march.