“At the Brazen Head in Cornhill Boston”

One of the landmarks of pre-Revolutionary Boston was the Brazen Head—a carved head covered in bronze. It hung outside a shop near the center of town, right across from the Town House.

Earlier this year I found that several histories say the Sign of the Brazen Head was a tavern. Charles Warren did so in Jacobin and Junto (1931), and Carl Seaburg in Boston Observed (1971). More recent examples include webpages from the usually reliable Massachusetts Historical Society and the Adverts 250 Project.

I’m hoping to cut off that misconception. Dublin may have had a Brazen Head Tavern, but Boston didn’t. The bronze head hanging on Cornhill street in Boston was the shop sign of a family of braziers, or makers and sellers of brass hardware.

What’s more, that family went through a lot of drama over the course of the 1700s, so over the next few days I’ll start telling The Saga of the Brazen Head.

The first page of that story is an advertisement in the 27 Apr 1730 New-England Weekly Journal:

But something changed. On 10 September James Jackson married Mary Hunter in King’s Chapel. I haven’t found out anything more about her, unfortunately. If she wasn’t Anglican before, she was now.

On 22 Feb 1731, Jackson placed a new ad in the New-England Weekly Journal with no hint of impending departure:

Jackson’s two advertisements located his place of business on Cornhill in central Boston, but I’m not sure if they specified different sites or the same site in different ways. By the time of his next ad, however, Jackson had settled on a shop location and found a way to make it stand out. In the 16 Dec 1734 Boston Gazette he announced in his largest notice yet:

For James Jackson, however, the shiny head probably just symbolized his brassware. And for the next forty years his Brazen Head shop would be a landmark near the center of Boston.

TOMORROW: A local landmark.

Earlier this year I found that several histories say the Sign of the Brazen Head was a tavern. Charles Warren did so in Jacobin and Junto (1931), and Carl Seaburg in Boston Observed (1971). More recent examples include webpages from the usually reliable Massachusetts Historical Society and the Adverts 250 Project.

I’m hoping to cut off that misconception. Dublin may have had a Brazen Head Tavern, but Boston didn’t. The bronze head hanging on Cornhill street in Boston was the shop sign of a family of braziers, or makers and sellers of brass hardware.

What’s more, that family went through a lot of drama over the course of the 1700s, so over the next few days I’ll start telling The Saga of the Brazen Head.

The first page of that story is an advertisement in the 27 Apr 1730 New-England Weekly Journal:

To be Sold by the Maker from London, a quantity of double refin’d hard metal Dishes and Plates, as also, sundry other things of the same metal, by Wholesale, or Retale, at Reasonable Rates, the Owner designing for London, in a Weeks time; to be seen at Mr. James Jackson, Founder, next Door to Mr. Stephen Beautineau in Cornhill, Boston.It looks like Jackson was referring to himself as both the goods’ “Maker from London” and their “Owner designing for London.” In other words, he had brought Boston the metropolis’s best brasswork, was ready to sell it for good prices, and then planned to return home.

But something changed. On 10 September James Jackson married Mary Hunter in King’s Chapel. I haven’t found out anything more about her, unfortunately. If she wasn’t Anglican before, she was now.

On 22 Feb 1731, Jackson placed a new ad in the New-England Weekly Journal with no hint of impending departure:

Brass Pump Chambers and large Brass Cocks, and all sorts of Founders Ware Cast, made or mended, at reasonable rates, by James Jackson Founder from London near William’s Court in Cornhil Boston: Likewise Exchanges or buys old Copper, Brass, Pewter, Lead or Iron.On 13 July, James and Mary Jackson baptized their first son William at King’s Chapel.

Jackson’s two advertisements located his place of business on Cornhill in central Boston, but I’m not sure if they specified different sites or the same site in different ways. By the time of his next ad, however, Jackson had settled on a shop location and found a way to make it stand out. In the 16 Dec 1734 Boston Gazette he announced in his largest notice yet:

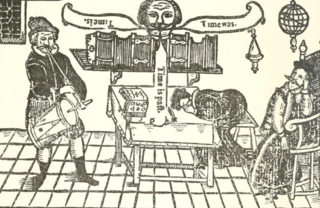

James Jackson Founder from London, at the Brazen Head in Cornhill Boston, makes and sells all forms of Brass Work, as Brass Hearths, Stove Grates, Fenders, Tongs & Shovels, Andirons, Dogs, Candlesticks, Snuffers & Stands, Plate Warmers, Brass Knockers for Doors, all sorts of Brass Work for Coaches or Chaises, or for Saddlers, Casts Mortars large and small, Brass Chambers for Pumps, brasses for Mills or Cranes, brass Cock Gun Work, small Bells, or any other sort of Cast Work; also sells London made pewter and Brasiers Ware, Brass Kettles large and small, Brass and Copper Warming-pans, of the best sort, Copper Tea Kettles, Coffee pots, Chocolate pots, Boiling-pots, Stueing and Frying pans, brass Skillets, Chafing Dishes, Steel Tongs and Shovels, London and Country made Jacks, Box Irons, Flat Irons, brass Nails by the Thousand, Iron Nails, Files, Melting pots, Gun powder and Shot, Swords & Belts, Horse pistoles, Cabinet Work Chamber & Kitchen Bellows, and sundry other sorts of Brasiers Ware, also Buys or Exchanges, or mends any sort of Copper, Pewter, Lead or Iron, at Reasonable Rates.Using the symbol and name of the Brazen Head was a, well, brazen move for the Londoner. According to a legend that New England Puritans no doubt disdained, the thirteenth-century monk Roger Bacon had invented a “brazen head”—a mechanical head that answered any yes-or-no question. That device showed up in a popular Elizabethan comedy (as shown above), and Daniel Defoe’s 1722 Journal of the Plague Year stated that a brazen head was one of the common symbols of a fortune-teller.

For James Jackson, however, the shiny head probably just symbolized his brassware. And for the next forty years his Brazen Head shop would be a landmark near the center of Boston.

TOMORROW: A local landmark.

2 comments:

I see that a volume of Boston’s town records published around the turn of the 20th century identified the Brazen Head as a tavern—perhaps the source of later misconceptions.

The "quantity of double refin’d hard metal Dishes and Plates, as also, sundry other things of the same metal" were not of brass, but undoubtedly of pewter with high tin content and little lead, alloyed and hardened with bismuth and/or antimony. "Hardmetal" and "Superfine Hardmetal" are common terms found among the secondary marks of eighteenth-century British pewterers. Boston pewterer/brasiers of Jackson's time working nearby, including John Holyoke (Dock Square) and Robert Bonynge (upper chamber of the town's shop #6 on the south side of the Town Dock), marked the pewterware they cast with such high-quality metal with a crowned "X." The 60 "N[ew] E[ngland] Hard Mettle Plates" in Jonathan Jackson's 1736 inveentory were appraised at £3 Old Tenor per dozen by Thomas Cushing, William Tyler, and Jonas Clark.

Post a Comment