“A More Circumstantial Account” of the Massacre

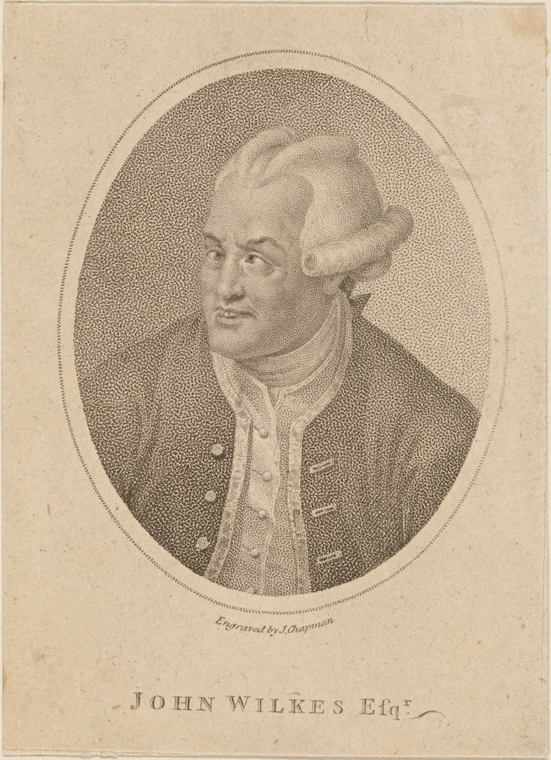

After describing what he saw on King Street during and after the shooting that became known as the Boston Massacre, William Palfrey’s 13 Mar 1770 letter to John Wilkes (shown here) continued:

For example:

As for stationing a sentinel in front of the Customs office:

Having reported that Capt. Thomas Preston had ordered his men to fire, Palfrey still had a good word for him:

The return of morning exhibited a most shocking spectacle; the gutters of the street running with blood, & the snow on the ground dyed crimson with the blood & brains of our fellow citizens.At that point Palfrey’s description of events shifted from what he experienced firsthand to what he’d heard other people say. His story became the Boston Whigs’ official line, what they wanted British sympathizers to understand about the event. But there were still some interesting statements reflecting what locals believed.

I went the next morning to view one of the bodies; when I was call’d upon a jury of inquest. In the course of the examination many witnesses were sworn, which enables me to give you a more circumstantial account of the matter than you may possibly receive from others, unless they had the same advantage.

For example:

It appear’d by the oaths of credible witnesses that Soldiers had been to the houses of some of their friends the Sunday Evening before this tragical event happen’d, and desir’d them, as they tender’d their own safety, to keep out of the way the two nights following: that there would be more blood shed then, than ever was known since the country had been settled.While these stories were meant to show a premeditated attack, they also show how soldiers had made “friends” in Boston.

As for stationing a sentinel in front of the Customs office:

This has been Customary since the Regiments were quarter’d here. The town have ever since kept a strong military watch, not only to prevent a rescue of the prisoners which was threatened by the soldiers, but also to prevent the lower sort of our own people from making any attempt to revenge the murder of their brethren.Genteel Whigs like Palfrey were willing to cast the common people as prone to rioting—as long as they could blame outside forces like lawless soldiers for provoking those riots.

The centinel at the Custom house door on seeing the lads approach loaded his piece, which they seeing gatherd near and laugh’d at him without offering any other insult.Actual eyewitnesses said that Pvt. Hugh White had loaded his musket, pounding the butt on the street, after the barbers’ apprentices had started to bother him. Throughout his letter, Palfrey insisted that locals had given the soldiers no reason to be nervous.

Having reported that Capt. Thomas Preston had ordered his men to fire, Palfrey still had a good word for him:

I cannot leave this subject without doing justice to Capt. Preston so far as to inform you that before this unfortunate event, he always behav’d himself unexceptionably & had the character of a sober, honest man & a good officer,—but Influence, fatal influence!The letter also tells us how locals watched the removal of soldiers from town:

The 29th have since been sent down [to Castle William], & the embarkation of the 14th begins this day. We shall soon get rid of our Military inmates, & I hope the town will thereby be restor’d to its former state of tranquility.In this striking passage, Palfrey raised the possibility of the Massacre provoking armed rebellion.

The people, tho’ drove almost to despair by this act of violence, and ready to take immediate vengeance on the offenders, were however restrain’d by the example & persuasion of many of those very men who have been on your side the water branded as incendiaries, & enemies of Great Britain. If there had ever been any intention in the Colonies to rebel, what a fair opening was here made! The military, without the least provocation, slaughtering the unarm’d, defenceless & innocent citizins. The Country for a great distance round was alarm’d & prepar’d themselves to join the people in Boston upon the first signal, & however despicable an opinion Collo. Dalrymple or his associates may entertain of the Bostonians, I assure you, Sir, forty thousand men could have been brot into the gates of this city at 48 hours warning.Finally, Palfrey noted a rumor that the Crown would appoint Col. William Dalrymple as successor to the departed governor, Francis Bernard:

I have just heard that Collo. Dalrymple is a candidate for our Government. I pray God most heartily we may never be govern’d by a Scotchman, & above all by a Military Scotchman.Palfrey’s correspondent, Wilkes, had of course made his political name attacking Scottish influence on the British government in his North-Britain magazine, so he would have responded well to badmouthing Scotchmen.

2 comments:

I know Wilkes wasn't exactly attractive and had some sort of squinting thing going on, but that engraving looks almost satirical.

Wilkes was cross-eyed, and artists working for his political opponents did make the most of that. But even the most dignified painted portrait cast half his face into shadow so as to avoid showing both eyes together.

Post a Comment