“No Copies of the whole or any Part to be taken”

On 24 Mar 1773, as described yesterday, Thomas Cushing promised Benjamin Franklin that he and other Massachusetts Whig legislators wouldn’t make any copies of the letters Franklin had sent from London with his approval.

Franklin had also specified that those letters should circulate only to a small number of men. But two days before Cushing wrote, they were in the hands of a man who wasn’t on Franklin’s list.

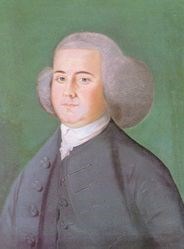

On 22 March John Adams wrote in his diary:

Adams’s diary entry recorded what he had heard and thought of the letters:

Decades later, on 28 Jan 1820, Adams told the botanist David Hosack how he had helped to spread the word about the documents that spring:

Adams returned the bundle to Cushing when he came back from riding circuit. Evidently those documents continued to circulate among Whigs in Boston, but still secretly. On the eve of the May session of the new Massachusetts General Court, Adams wrote in his diary:

The next day, Gov. Hutchinson vetoed Adams’s membership, along with two other men. So he needn’t have fretted.

TOMORROW: The letters in the legislature.

Franklin had also specified that those letters should circulate only to a small number of men. But two days before Cushing wrote, they were in the hands of a man who wasn’t on Franklin’s list.

On 22 March John Adams wrote in his diary:

This Afternoon received a Collection of Seventeen Letters, written from this Province, Rhode Island, Connecticutt and N. York, by [Thomas] Hutchinson, [Andrew] Oliver, [Dr. Thomas] Moffat, [Charles] Paxton, and [George] Rome, in the Years 1767, 8, 9.By 1773 Hutchinson was governor, Oliver lieutenant governor, and Paxton still a Customs Commmissioner. Dr. Moffat of Connecticut and Rome of Rhode Island were supporters of the royal governments in those colonies, which still elected their governors. The full collection also included letters Nathaniel Rogers, a young merchant and nephew of Hutchinson who had died in 1770, and from Robert Auchmuty, an admiralty court judge, to Hutchinson.

Adams’s diary entry recorded what he had heard and thought of the letters:

They came from England under such Injunctions of Secrecy, as to the Person to whom they were written, by whom and to whom they are sent here, and as to the Contents of them, no Copies of the whole or any Part to be taken, that it is difficult to make any public Use of them.Adams used the word “Secrecy” twice in three short paragraphs—once referring to the leaker’s conditions about the letters, and again referring to the supposed schemes of the men who wrote those letters. In Adams’s eyes, some secrecy was necessary, other secrecy was nefarious.

These curious Projectors and Speculators in Politicks, will ruin this Country—cool, thinking, deliberate Villains, malicious, and vindictive, as well as ambitious and avaricious.

The Secrecy of these epistolary Genii is very remarkable—profoundly secret, dark, and deep

Decades later, on 28 Jan 1820, Adams told the botanist David Hosack how he had helped to spread the word about the documents that spring:

I was one of the first Persons to whom Mr Cushing communicated the great bundle of Letters of Hutchinson and Oliver, which have been transmitted to him as Speaker of the House of Representatives by Dr Franklin their Agent in London—I was permitted to carry them with me upon a Circuit of our Judicial Court—and to Communicate them to the chosen few—While I’ve learned to take Adams’s late-life reminiscences about his central place in some incidents of the Revolution with a grain of salt, this story fits with the contemporaneous evidence.

they excited no suprise; excepting at the Miracle of their acquisition—how that could have been performed nobody could conjecture—none doubted their Authenticity; for the hand writing was full proof, and besides all the leading Men in opposition to the Ministery had long been fully convinced that the writers were guilty of such malignant representation—and that those representations had suggested to the Ministery their nefarious projects

Adams returned the bundle to Cushing when he came back from riding circuit. Evidently those documents continued to circulate among Whigs in Boston, but still secretly. On the eve of the May session of the new Massachusetts General Court, Adams wrote in his diary:

The Plotts, Plans, Schemes, and Machinations of this Evening and Night, will be very numerous. By the Number of Ministerial, Governmental People returned, and by the Secrecy of the Friends of Liberty, relating to the grand discovery of the compleat Evidence of the whole Mystery of Iniquity, I much fear the Elections will go unhappily.The “Elections” Adams referred to there weren’t the towns’ elections of representatives to the new house, which had already taken place. Rather, he meant the choice by that new house and the outgoing Council of men to sit on the new Council. Adams knew that he himself was up for consideration, and he had mixed feelings about that:

For myself, I own I tremble at the Thought of an Election. What will be expected of me? What will be required of me? What Duties and Obligations will result to me, from an Election? What Duties to my God, my King, my Country, my Family, my Friends, myself? What Perplexities, and Intricacies, and Difficulties shall I be exposed to? What Snares and Temptations will be thrown in my Way? What Self denials and Mortifications shall I be obliged to bear?The legislature’s strong Whig majority indeed voted Adams onto the Council, the last of the eighteen men named from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. (There were separate choices for Councilors from the Plymouth, Maine, and northern Maine districts and for two members at large.)

The next day, Gov. Hutchinson vetoed Adams’s membership, along with two other men. So he needn’t have fretted.

TOMORROW: The letters in the legislature.

No comments:

Post a Comment