“This British Drum was captured at Bunker Hill”?

Yesterday I quoted the traditional story of Levi Smith’s “Bunker Hill Drum,” as published in the Boston Globe in 1903.

Some details of that story seem unlikely on their face. To start with, the drum allegedly came into American hands this way:

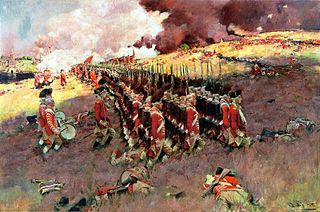

During the Battle of Bunker Hill, provincial positions were under pretty constant cannon fire from Royal Navy ships, Copp’s Hill, and field guns firing grapeshot. There were angry British soldiers at the bottom of the hill. Some of the redcoats lying on the hillside might still have been alive and ready to attack again. How easy is it to believe that a provincial man would leave the protection of the redoubt or the other barriers he and his unit had built for themselves, scramble downhill past British casualties, grab a drum off a corpse, and climb back up safely? How happy would his officers have been to see that?

And then what did that putative Rhode Island soldier do with his prize? One might think he deserved to keep it, but:

Of course, many times people do behave recklessly and illogically. No sources in the first hundred years after the battle describe a soldier popping out from the provincial lines to grab a souvenir drum and rushing back, but we can’t say that definitely didn’t happen.

Richard Spicer investigated this story for the National Parks of Boston’s newsletter, The Broadside, in 2010 (P.D.F. download), and he found bigger holes.

To start with, when Gen. Nathanael Greene brought the Rhode Island regiments north to the siege lines around Boston, they naturally ended up on the southern wing, in Roxbury and Dorchester. Gen. Artemas Ward kept them there through the battle up in Charlestown, helping to guard that route out of Boston. No Rhode Island units were in the Battle of Bunker Hill at all.

What’s more, Spicer adds:

By that time, the British army had dug in on Bunker’s Hill, the highest point of the Charlestown peninsula. They remained in their fortification there until the evacuation of March 1776. Then the Continental troops from that side of the siege lines marched onto the peninsula, both regular army and recently mobilized militia companies. In the fort they found dummies in British uniforms—“Lifeless Sentries,” in Gen. John Sullivan’s words. They probably also found abandoned military equipment, as other regiments were finding in Boston.

Among that equipment left on Bunker’s Hill might well have been a damaged army drum—not worth enough to the king’s army to be worth carrying away, but in salvageable condition for the less equipped Continentals. The Rhode Island soldiers could have grabbed that and eventually chosen one of their drummers to take it home and repair it.

That’s one possible way a “British Drum was captured at Bunker Hill”—the location, not the battle. Smith might have indeed been given the damaged drum “by lot” since it wasn’t much of a prize, after all. But he fixed it up and passed it on to his descendants, who also went to war.

But that would be a rather poor story, so over time the narrative of an old drum might have gotten blown up into the legend of a man seizing a drum in the midst of the battle. Whatever happened, the drum is in the Bunker Hill Museum, representing the combat of the battle.

Some details of that story seem unlikely on their face. To start with, the drum allegedly came into American hands this way:

The lad who carried the drum when the Britishers made their first attack on Breed’s hill, was shot down at the first volley, and the barrel of his drum almost riddled with bullets. After the second assault, and while King George’s troops were being rallied for their third and successful attack, one of the members of the Rhode Island company in question went over the intrenchments and carried back with him this relic.Now it’s true that the British command’s list of casualties after the battle includes one drummer killed, as well as twelve wounded. But that’s far as the plausibility goes.

During the Battle of Bunker Hill, provincial positions were under pretty constant cannon fire from Royal Navy ships, Copp’s Hill, and field guns firing grapeshot. There were angry British soldiers at the bottom of the hill. Some of the redcoats lying on the hillside might still have been alive and ready to attack again. How easy is it to believe that a provincial man would leave the protection of the redoubt or the other barriers he and his unit had built for themselves, scramble downhill past British casualties, grab a drum off a corpse, and climb back up safely? How happy would his officers have been to see that?

And then what did that putative Rhode Island soldier do with his prize? One might think he deserved to keep it, but:

the men in the company drew lots for its possession, and afterward, by unanimous consent, gave it to the Rhode Island drummer boy, Levi Smith.So a man risked his life for the drum, then gave it up to the company. They drew lots, so the drum probably went to someone else. But then everyone decided it should go to a third person, the drummer? That’s a roundabout way of conveying a drum to the person in the company who uses a drum.

Of course, many times people do behave recklessly and illogically. No sources in the first hundred years after the battle describe a soldier popping out from the provincial lines to grab a souvenir drum and rushing back, but we can’t say that definitely didn’t happen.

Richard Spicer investigated this story for the National Parks of Boston’s newsletter, The Broadside, in 2010 (P.D.F. download), and he found bigger holes.

To start with, when Gen. Nathanael Greene brought the Rhode Island regiments north to the siege lines around Boston, they naturally ended up on the southern wing, in Roxbury and Dorchester. Gen. Artemas Ward kept them there through the battle up in Charlestown, helping to guard that route out of Boston. No Rhode Island units were in the Battle of Bunker Hill at all.

What’s more, Spicer adds:

Smith’s own record of service calls this [story] further into question. Though he died in 1827, his widow lived well beyond, long enough to qualify for a pension authorized by an 1838 Act of Congress. She therefore filed a detailed application in 1840, including four affidavits from men who knew or had served with her husband during the war, and all records are consistent: Levi Smith served as a drummer intermittently about 12-13 months not in the Continental Army, but in the Rhode Island militia only, from December 1776 to March 1781; there is no record for any service in 1775; and there is no mention of Bunker Hill.Given that evidence, can the “Bunker Hill Drum” have any connection to Bunker Hill at all? I have a theory which fits pretty well with the statement on the drum itself:

This British Drum was captured at Bunker Hill, and assigned by lot to Levi Smith, a DrummerAfter Gen. George Washington arrived in Massachusetts and sized up the siege lines in July 1775, he rearranged the Continental forces. He made Greene and the Rhode Island troops part of Gen. Charles Lee’s brigade on the north wing of the lines, in Cambridge and west Charlestown.

By that time, the British army had dug in on Bunker’s Hill, the highest point of the Charlestown peninsula. They remained in their fortification there until the evacuation of March 1776. Then the Continental troops from that side of the siege lines marched onto the peninsula, both regular army and recently mobilized militia companies. In the fort they found dummies in British uniforms—“Lifeless Sentries,” in Gen. John Sullivan’s words. They probably also found abandoned military equipment, as other regiments were finding in Boston.

Among that equipment left on Bunker’s Hill might well have been a damaged army drum—not worth enough to the king’s army to be worth carrying away, but in salvageable condition for the less equipped Continentals. The Rhode Island soldiers could have grabbed that and eventually chosen one of their drummers to take it home and repair it.

That’s one possible way a “British Drum was captured at Bunker Hill”—the location, not the battle. Smith might have indeed been given the damaged drum “by lot” since it wasn’t much of a prize, after all. But he fixed it up and passed it on to his descendants, who also went to war.

But that would be a rather poor story, so over time the narrative of an old drum might have gotten blown up into the legend of a man seizing a drum in the midst of the battle. Whatever happened, the drum is in the Bunker Hill Museum, representing the combat of the battle.

No comments:

Post a Comment