Underwater Archeology off Yorktown

This Daily Press article out of Newport News about marine archeology in the York River near Yorktown speaks to human perseverance in a couple of ways.

First, it runs down all the ways Gen. Cornwallis tried to drive off the French fleet at the river’s mouth so that he could evacuate instead of surrendering.

The article also talks about the archeologists’ persistent efforts to investigate those wrecks since the Bicentennial period as public funding for such endeavors was being scuttled. The investigation is led, as was the one in the 1980s, by John Broadwater, then Virginia’s state underwater archeologist.

First, it runs down all the ways Gen. Cornwallis tried to drive off the French fleet at the river’s mouth so that he could evacuate instead of surrendering.

He sets a few of his own ships afire and tries to drift them into the French warships. No luck.Which left a lot of ships’ hulls in the river.

He tries to slip away, loading his men into small boats to make for Gloucester, but a storm roars in and swamps the attempt.

Finally, he resorts to a tactic that’s been used by others: He sacrifices his own fleet.

Cornwallis sends a line of his ships toward the Yorktown beach until they run aground, forming a barrier he hopes will stop the French from landing troops.

To keep the rest out of his convoy out of enemy hands — as well as block the river with wreckage — Cornwallis issues orders to scuttle. Holes are drilled or chiseled in hulls and the vessels sink.

The article also talks about the archeologists’ persistent efforts to investigate those wrecks since the Bicentennial period as public funding for such endeavors was being scuttled. The investigation is led, as was the one in the 1980s, by John Broadwater, then Virginia’s state underwater archeologist.

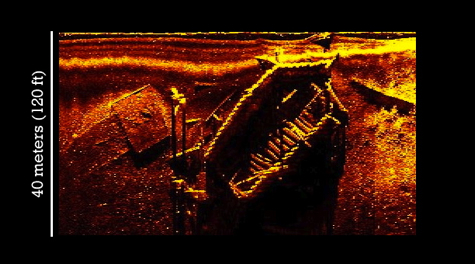

In 1988, a 20-page spread in National Geographic detailed their accomplishments — more than 5,000 relics recovered for posterity from one wreck alone, a ship named Betsy.On the plus side, it looks like new technology has made locating wrecks easier than it was before. The picture above, coming from the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences, shows a “side-scan sonar image” of a newly found wreck. Of course, the team needs access to that technology and more.

But state budget cuts came shortly after, and Broadwater’s position was axed. Work stopped on the project, and relics went into storage — many of them uninspected, which led to a scramble just last year, when live hand grenades from The Betsy were discovered sitting on shelves at the Department of Historic Resources in Richmond.

Now, at 75 years old, Broadwater has come home. He’s working with volunteers — some from the old Betsy days. Most of their equipment is donated. Most expenses are covered by the partners’ own money.

No comments:

Post a Comment