Ripples from the Boston Tea Party in 1774

Without the Boston Massacre reenactment looming over my schedule this year, I’ll devote the next few days to the events of early March 1774.

That was less than three months after the Boston Tea Party, and the ripples from that big splash in the harbor were still spreading.

Most Bostonians were excited about how the event had turned out. The local Sons of Liberty had kept the tea tax from being collected, but they hadn’t hurt any other property or any people. Other towns and ports along the American coast sent messages of support.

On 20 January an agreement among Boston merchants and shopkeepers to stop selling all tea, regardless of tax status, took effect. The Whigs hauled three barrels of tea to King Street and burned them in front of the customs house.

To be sure, there was still some tea circulating in the colony. A fourth tea ship, the William, had wrecked on Cape Cod, and some chests had been salvaged from the wreck. Local Whig crowds were chasing those down.

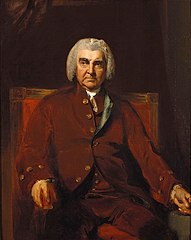

Meanwhile, the London government was digesting reports of disorder in Boston the previous fall—even before the tea destruction. Ministers considered the big public meetings and the attack on Richard Clarke’s family warehouse described here. On 5 February, Secretary of State Dartmouth sent Attorney-General Edward Thurlow (1731-1806, shown above) evidence about those events.

Six days later, Thurlow and Solicitor-General Alexander Wedderburn replied that several Bostonians had likely committed high treason. They specifically noted:

Also in early February, King George III interviewed Gen. Thomas Gage, commander in chief of the army in North America. Gage stated “his readiness, though so lately come from America, to return at a day’s notice if the conduct of the Colonies should induce the directing coercive measures.” He also opined that those measures wouldn’t need any more troops.

And all the while, a ship called the Fortune was plying the Atlantic toward Boston, carrying more tea.

That was less than three months after the Boston Tea Party, and the ripples from that big splash in the harbor were still spreading.

Most Bostonians were excited about how the event had turned out. The local Sons of Liberty had kept the tea tax from being collected, but they hadn’t hurt any other property or any people. Other towns and ports along the American coast sent messages of support.

On 20 January an agreement among Boston merchants and shopkeepers to stop selling all tea, regardless of tax status, took effect. The Whigs hauled three barrels of tea to King Street and burned them in front of the customs house.

To be sure, there was still some tea circulating in the colony. A fourth tea ship, the William, had wrecked on Cape Cod, and some chests had been salvaged from the wreck. Local Whig crowds were chasing those down.

Meanwhile, the London government was digesting reports of disorder in Boston the previous fall—even before the tea destruction. Ministers considered the big public meetings and the attack on Richard Clarke’s family warehouse described here. On 5 February, Secretary of State Dartmouth sent Attorney-General Edward Thurlow (1731-1806, shown above) evidence about those events.

Six days later, Thurlow and Solicitor-General Alexander Wedderburn replied that several Bostonians had likely committed high treason. They specifically noted:

The conduct of Mr. [William] Molynieux, and…[William] Denny, [Dr. Joseph] Warren, [Dr. Benjamin] Church, and Jonathan [Williams?] who in the characters of a committee went to the length of attacking Clarke, are chargeable with the crime of High Treason; and if it can be established in evidence, that they were so employed by the select men of Boston, Town Clerk, and members of the House of Representatives, these also are guilty of the same offence.The law officers also cited Samuel Adams and Dr. Thomas Young for their work on the committee of correspondence and John Hancock for participating in the armed patrols that kept the tea from being landed. Of course, securing prosecutions of any of those men was a bigger challenge.

Also in early February, King George III interviewed Gen. Thomas Gage, commander in chief of the army in North America. Gage stated “his readiness, though so lately come from America, to return at a day’s notice if the conduct of the Colonies should induce the directing coercive measures.” He also opined that those measures wouldn’t need any more troops.

And all the while, a ship called the Fortune was plying the Atlantic toward Boston, carrying more tea.

No comments:

Post a Comment