Looking Back on the Owen Richards Attack

Last December, starting here, I wrote about the tar-and-feathers attack on a Customs employee named Owen Richards in May 1770.

The fallout from that event lasted for years, so I’m going to resume the story.

But first, for review, here’s the merchant John Rowe’s summary of the attack in his diary for 18 May:

I can’t find a precedent for making Richards swear an oath and drop a bottle, though. It looks like a folk ritual of some sort, with the extra appeal of breaking stuff.

As Salisbury reported, the crowd eventually let Richards’s friends pull him away and get him home safely.

TOMORROW: Going to court.

The fallout from that event lasted for years, so I’m going to resume the story.

But first, for review, here’s the merchant John Rowe’s summary of the attack in his diary for 18 May:

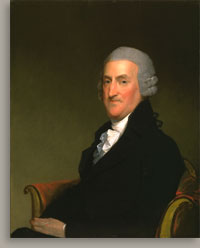

Just as I was going to bed there was a very great Hallooing in the street & a mob of upwards a thousand people—it seems they had got an informer & put him in a Cart, covered with Tar & Feathers & so exhibited him thro’ the Streets.For a more detailed description, we can turn to Esther Forbes’s Paul Revere and the World He Lived In, quoting the merchant Samuel Salisbury (shown above, decades later):

I perceived candles in a number of windows,The mob that attacked George Gailer, another man accused of helping the Customs service, in October 1769 also made him “carry the lantren in his hand & calling to all the inhabitince to put Candles in their Windoes.”

what, thinks I, is there an illumination tonight?

Getting home I was informed that an Informer had been carted through the streets, Tarred and feathered.

After I had been to the Barber’s my Curiosity led me to the point at New Boston [the western tip of the peninsula] where I found the Informer in a Cart before Capt [John] Homer’s door surrounded with a great number of People

he had his shirt taken off & his bare skin tarred & Feathered. Sometimes they would make him say one thing sometimes another. Sometimes he must hold the Lanthorn this way, sometimes that, then he must hold up a glass Bottle & Swear he would never do so agin & let the bottle fall down & break & then Huzzah—

from thence they carried him into King Street Let him get out of the Cart made a lane down the street where 3 or 4 carried him off from the multitude in safety, being about nine o’clock.

I can’t find a precedent for making Richards swear an oath and drop a bottle, though. It looks like a folk ritual of some sort, with the extra appeal of breaking stuff.

As Salisbury reported, the crowd eventually let Richards’s friends pull him away and get him home safely.

TOMORROW: Going to court.

4 comments:

Captain John Homer was a prominent member of the Sons of Liberty in 1770 and even has his name inscribed on the Sons of Liberty Bowl as one of the presenters to the "Glorious Ninety Two." He later became a Loyalist and was amongst those evacuated from Boston by the British Navy in 1776. His business was obviously ruined and his property was confiscated. He settled in Nova Scotia.

Capt. Homer was indeed on the Whig side in the late 1760s, though I don’t see him as prominent. Curiously, his name doesn’t appear on the list of refugees evacuating with the British military in 1776 or on the Massachusetts Banishment Acts. But he indeed died in Nova Scotia. There are more details to be found about him.

The list of refugees evacuating with the British Army in 1776 is known to be incomplete. Homer's family history indicates he left with the British Army.

Yes, and the question is whether that family tradition is accurate. If Homer’s name appeared on the March 1776 list, we could feel sure it was. Since it doesn’t, we don’t know that that tradition is mistaken, but we still don’t have contemporaneous evidence for it.

One piece of evidence to consider is how Hannah Homer’s death in 1786 is recorded in the Barrington, Nova Scotia, church records: “1786 March 10 Hannah Homer 51 years 5 months & 12 days wife to John Homer Esq. from Boston in July 4 1775.” The last date has no bearing on Hannah Homer’s age or marriage. It appears to relate to when she and John left from Boston or arrived in Nova Scotia. That would indicate the Homers departed Boston months before the British military. Why the Massachusetts government didn’t ban him and confiscate his property is still a question.

As for Capt. Homer’s political activity back in Boston, he shows up on two lists: the small club that commissioned the Revere punch bowl celebrating the Circular Letter and the large dinner in Dorchester in 1769. I can’t connect him to any other groups or activities. That’s why I don’t see as prominent, though he was definitely on the Whig side at the time.

Post a Comment