Nostalgia “a frequent disease in the American army”

The words “nostalgia” and “nostalgic” don’t appear in any of the letters and other sources available at Founders Online. But of course most of those writers weren’t physicians.

American doctors did use the diagnosis of nostalgia, learning it from European medical authorities. Their uses reflected the original meaning of the word as homesickness rather than how we use the term today.

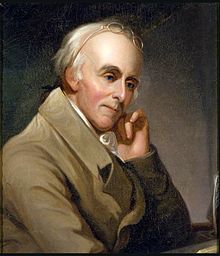

In “An Account of the Influence of the Military and Political Events of the American Revolution upon the Human Body” (published with other essays in 1789), Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote:

Rush’s memory may have been faulty about dates. He said Gen. Gates told him in 1776 that nostalgia cleared up because of the threat from Gen. Burgoyne. In that year, Gen. Guy Carleton was in command, with Burgoyne serving under him. Burgoyne led the bigger advance from Canada in 1777. Rush may have amalgamated the events in his mind, but such detail doesn’t matter much to how Rush understood nostalgia.

Dr. James Thacher of Plymouth served the entire war as a surgeon’s mate and military surgeon for the Continental Army. Decades later, in 1823, he adapted his wartime diaries into A Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War.

In that book Thacher wrote under the date of late June 1780:

Both of these doctors described nostalgia as prevalent in soldiers away from home (particularly from New England), not in those soldiers who had been through hard fighting. In fact, both of these American doctors saw “the prospect of a battle” as dispelling nostalgia, and Thacher viewed “old soldiers” as less prone to it than fresh militiamen.

It’s possible that other American doctors diagnosed Revolutionary soldiers or veterans with nostalgia based on symptoms and circumstances that correspond better with what we call P.T.S.D. I’ve looked for such cases, haven’t found any, and would welcome references.

TOMORROW: A British case study.

American doctors did use the diagnosis of nostalgia, learning it from European medical authorities. Their uses reflected the original meaning of the word as homesickness rather than how we use the term today.

In “An Account of the Influence of the Military and Political Events of the American Revolution upon the Human Body” (published with other essays in 1789), Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote:

THE NOSTALGIA of Doctor [William] Cullen, or the homesickness, was a frequent disease in the American army, more especially among the soldiers of the New-England states. But this disease was suspended by the superior action of the mind under the influence of the principles which governed common soldiers in the American army.Rush’s essay was as much political as medical. He wanted to make the case that, while the disruptions of revolution and war caused stress and illness, the best remedy was more republicanism. Nothing cured the New Englanders’ nostalgia quicker than the imminent prospect of being hanged as traitors by an invading monarchical army.

Of this General [Horatio] Gates furnished me with a remarkable instance in 1776, soon after his return from the command of a large body of regular troops and militia at Ticonderoga. From the effects of the nostalgia, and the feebleness of the discipline, which was exercised over the militia, desertions were very frequent and numerous in his army, in the latter part of the campaign; and yet during the three weeks in which the general expected every hour an attack to be made upon him by General [John] Burgoyne, there was not a single desertion from his army, which consisted at that time of 10,000 men.

Rush’s memory may have been faulty about dates. He said Gen. Gates told him in 1776 that nostalgia cleared up because of the threat from Gen. Burgoyne. In that year, Gen. Guy Carleton was in command, with Burgoyne serving under him. Burgoyne led the bigger advance from Canada in 1777. Rush may have amalgamated the events in his mind, but such detail doesn’t matter much to how Rush understood nostalgia.

Dr. James Thacher of Plymouth served the entire war as a surgeon’s mate and military surgeon for the Continental Army. Decades later, in 1823, he adapted his wartime diaries into A Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War.

In that book Thacher wrote under the date of late June 1780:

Our troops in camp are in general healthy, but we are troubled with many perplexing instances of indisposition, occasioned by absence from home, called by Dr. Cullen nostalgia, or home sickness. This complaint is frequent among the militia, and recruits from New England. They become dull and melancholy, with loss of appetite, restless nights, and great weakness. In some instances they become so hypochondriacal as to be proper subjects for the hospital.Rush and Thacher didn’t use the term “nostalgia” in a way that we can easily map onto the modern diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Thacher definitely saw signs of anxiety and depression with physical manifestations. Rush linked the condition to desertions. But they didn’t see nostalgia as a reaction to combat.

This disease is in many instances cured by the raillery of the old soldiers, but is generally suspended by a constant and active engagement of the mind, as by the drill exercise, camp discipline, and by uncommon anxiety, occasioned by the prospect of a battle.

Both of these doctors described nostalgia as prevalent in soldiers away from home (particularly from New England), not in those soldiers who had been through hard fighting. In fact, both of these American doctors saw “the prospect of a battle” as dispelling nostalgia, and Thacher viewed “old soldiers” as less prone to it than fresh militiamen.

It’s possible that other American doctors diagnosed Revolutionary soldiers or veterans with nostalgia based on symptoms and circumstances that correspond better with what we call P.T.S.D. I’ve looked for such cases, haven’t found any, and would welcome references.

TOMORROW: A British case study.

No comments:

Post a Comment