Jacobin “Air Looms” in London

James Tilly Matthews (1770-1815) came to London from Wales to work as a tea broker in the early 1790s.

He became an acolyte of the Rev. David Williams (1738-1816), a reformist minister and philosopher who had hosted Benjamin Franklin back in 1774 when the American needed a refuge from the political pressure over his leak of Thomas Hutchinson’s letters.

In the early 1790s, Williams was active in promoting peace between Britain and Revolutionary France, but the execution of Louis XVI discouraged him. Matthews kept at that campaign, though, working through Girondist contacts.

Then a change of government in Paris brought the Jacobins to power and Matthews under suspicion. He was locked up for three years as a possible British spy. Eventually a new French government concluded Matthews was insane and sent him back to Britain.

On 30 Dec 1796 Matthews went into the House of Commons and started shouting that the Home Secretary, Lord Liverpool, was a traitor. The British government also decided Matthews was insane, and by January 1793 he was in the Bethlem or Bedlam Hospital, where he spent the next two decades.

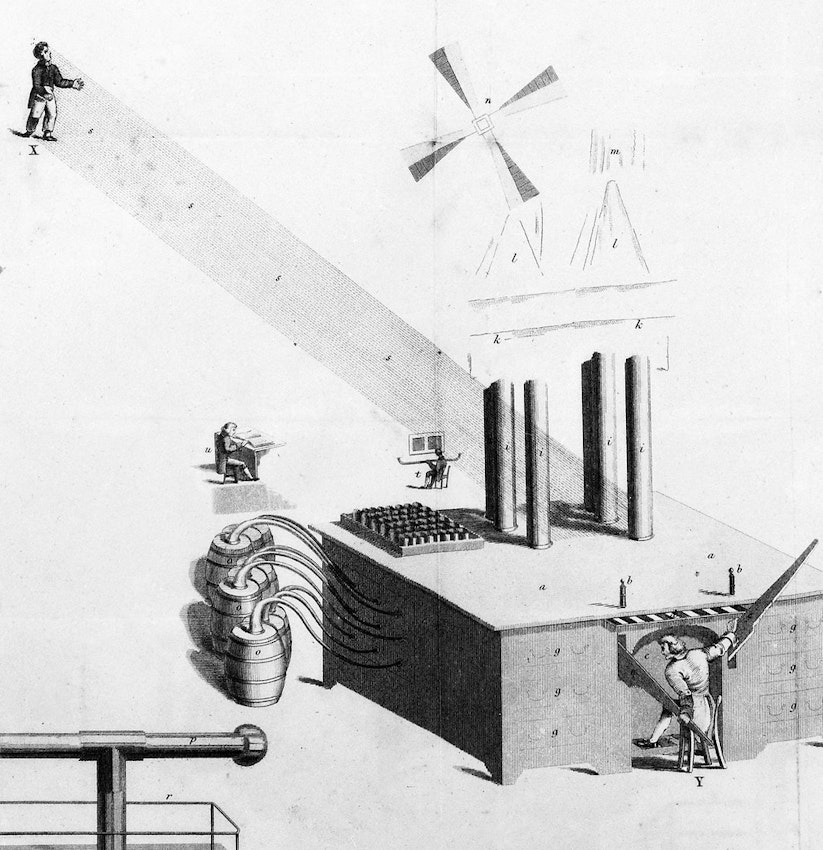

In 1809 there was a dispute among doctors over whether Matthews was rational. The Bethlem apothecary, John Haslam, supported his position with a book describing Matthews’s delusions in detail, complete with pictures. The Public Domain Review shares Mike Jay’s article about that book.

In particular, Matthews said, he was tormented by a gang of people operating a nearby “Air Loom”:

James Tilly Matthews is now considered one of the earliest well documented cases of paranoid schizophrenia. He’s also notable because he interpreted the voices and impulses he experienced not through supernatural or spiritual factors but through newly emerging science. Matthews is thus also one of the earliest examples in Jeffrey Sconce’s 2019 study, The Technical Delusion: Electronics, Power, Insanity.

Back in 2010 I wrote about another such example. In 1776 Lt. Neil Wanchope of the Royal Navy’s marines began to alarm fellow officers aboard H.M.S. Thetis, “knocking against the 1st Lieutenant’s cabin desiring him to leave off electrifying and murdering him.” Like Matthews, Wanchope understood his mental experiences using one of the period’s most advanced scientific concepts.

He became an acolyte of the Rev. David Williams (1738-1816), a reformist minister and philosopher who had hosted Benjamin Franklin back in 1774 when the American needed a refuge from the political pressure over his leak of Thomas Hutchinson’s letters.

In the early 1790s, Williams was active in promoting peace between Britain and Revolutionary France, but the execution of Louis XVI discouraged him. Matthews kept at that campaign, though, working through Girondist contacts.

Then a change of government in Paris brought the Jacobins to power and Matthews under suspicion. He was locked up for three years as a possible British spy. Eventually a new French government concluded Matthews was insane and sent him back to Britain.

On 30 Dec 1796 Matthews went into the House of Commons and started shouting that the Home Secretary, Lord Liverpool, was a traitor. The British government also decided Matthews was insane, and by January 1793 he was in the Bethlem or Bedlam Hospital, where he spent the next two decades.

In 1809 there was a dispute among doctors over whether Matthews was rational. The Bethlem apothecary, John Haslam, supported his position with a book describing Matthews’s delusions in detail, complete with pictures. The Public Domain Review shares Mike Jay’s article about that book.

In particular, Matthews said, he was tormented by a gang of people operating a nearby “Air Loom”:

The Air Loom worked, as its name suggests, by weaving “airs”, or gases, into a “warp of magnetic fluid” which was then directed at its victim. Matthews’ explanation of its powers combined the cutting-edge technologies of pneumatic chemistry and the electric battery with the controversial science of animal magnetism, or mesmerism. The finer detail becomes increasingly strange. It was fuelled by combinations of “fetid effluvia”, including “spermatic-animal-seminal rays”, “putrid human breath”, and “gaz from the anus of the horse”, and its magnetic warp assailed Matthews’ brain in a catalogue of forms known as “event-workings”. . . .Similar machines were at work in other parts of the capital, Matthews said, and Prime Minister William Pitt was under the gang’s control.

The machine’s operators were a gang of undercover Jacobin terrorists, who Matthews described with haunting precision. Their leader, Bill the King, was a coarse-faced and ruthless puppetmaster who “has never been known to smile”; his second-in-command, Jack the Schoolmaster, took careful notes on the Air Loom’s operations, pushing his wig back with his forefinger as he wrote. The operator was a sinister, pockmarked lady known only as the “Glove Woman”. The public face of the gang was a sharp-featured woman named Augusta, superficially charming but “exceedingly spiteful and malignant” when crossed, who roamed London’s west end as an undercover agent.

James Tilly Matthews is now considered one of the earliest well documented cases of paranoid schizophrenia. He’s also notable because he interpreted the voices and impulses he experienced not through supernatural or spiritual factors but through newly emerging science. Matthews is thus also one of the earliest examples in Jeffrey Sconce’s 2019 study, The Technical Delusion: Electronics, Power, Insanity.

Back in 2010 I wrote about another such example. In 1776 Lt. Neil Wanchope of the Royal Navy’s marines began to alarm fellow officers aboard H.M.S. Thetis, “knocking against the 1st Lieutenant’s cabin desiring him to leave off electrifying and murdering him.” Like Matthews, Wanchope understood his mental experiences using one of the period’s most advanced scientific concepts.

No comments:

Post a Comment