Fallout from the “Tradesmen’s Protest”

Bostonians gathered on short notice in Faneuil Hall for a town meeting on 5 Nov 1773. Their first act was to choose John Hancock as moderator.

The reason for this meeting was the news that the East India Company was shipping tea to America. By a process not spelled out, the result would be: “our liberties for which we have long struggled, will be lost to them and their Posterity.”

The town’s eventual response to that news was to endorse the resolutions of a Philadelphia meeting condemning the Tea Act, the company, and anyone who cooperated with it.

A closer problem, however, was that some locals had distributed a handbill titled “Tradesmen’s Protest Against the Proceedings of the Merchants Relative to the New Importation of Tea,” printed by Ezekiel Russell. The Massachusetts Historical Society has digitized that flyer here.

A group of merchants, claiming to speak for Boston’s business community, had issued a call to boycott tea. The “Tradesmen’s” handbill responded in kind, also claiming to speak for local businessmen. “You are hereby advised and warned by no means to be taken in by the deceitful Bait of those who falsely stile themselves Friends of Liberty,” it said. “WE are resolved, by Divine Assistance,…to Buy and Sell when and where we please; herein hoping for the Protection of good Government.”

At the town meeting, someone moved for all tradesman to gather on the south side of the hall so they could vote on whether they agreed with this handbill. This question “passed in the Negative, unanimously—there being in the estimation of the Town at least four hundred Tradesmen present.”

That afternoon Ezekiel Russell appeared and addressed the gathering. The official record reads:

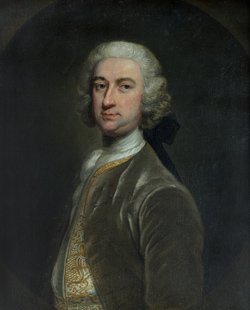

In the morning, “one of the Inhabitants openly declared that he saw Charles Paxton one of the Commissioners of the Customs, giving them away the Day before in Kings Street.” Paxton (shown above) had been one of the most disliked royal officials in Boston for over a decade.

On 10 November, Commissioner Paxton went to justice of the peace Edmund Quincy and swore to a deposition:

TOMORROW: Talking to the tea consignees.

The reason for this meeting was the news that the East India Company was shipping tea to America. By a process not spelled out, the result would be: “our liberties for which we have long struggled, will be lost to them and their Posterity.”

The town’s eventual response to that news was to endorse the resolutions of a Philadelphia meeting condemning the Tea Act, the company, and anyone who cooperated with it.

A closer problem, however, was that some locals had distributed a handbill titled “Tradesmen’s Protest Against the Proceedings of the Merchants Relative to the New Importation of Tea,” printed by Ezekiel Russell. The Massachusetts Historical Society has digitized that flyer here.

A group of merchants, claiming to speak for Boston’s business community, had issued a call to boycott tea. The “Tradesmen’s” handbill responded in kind, also claiming to speak for local businessmen. “You are hereby advised and warned by no means to be taken in by the deceitful Bait of those who falsely stile themselves Friends of Liberty,” it said. “WE are resolved, by Divine Assistance,…to Buy and Sell when and where we please; herein hoping for the Protection of good Government.”

At the town meeting, someone moved for all tradesman to gather on the south side of the hall so they could vote on whether they agreed with this handbill. This question “passed in the Negative, unanimously—there being in the estimation of the Town at least four hundred Tradesmen present.”

That afternoon Ezekiel Russell appeared and addressed the gathering. The official record reads:

He then acquainted the Town that he was the Printer of the Paper called the Tradesmen’s Protest against the Merchants, & that he was paid for the same by the Person who Employed him.—this Information was not given at the desire of the Town; it being their sense, that as a Town they had nothing to do with the Printer or Author of the said Paper——Russell had a reputation for printing almost anything as long as he was paid. I can’t tell if in this case he kept the name of his customer secret or if town clerk William Cooper chose not to record it. In any event, the point of this item in the meeting record was that Russell was below official notice.

In the morning, “one of the Inhabitants openly declared that he saw Charles Paxton one of the Commissioners of the Customs, giving them away the Day before in Kings Street.” Paxton (shown above) had been one of the most disliked royal officials in Boston for over a decade.

On 10 November, Commissioner Paxton went to justice of the peace Edmund Quincy and swore to a deposition:

WHEREAS a Number of the Inhabitants of the Town of Boston being assembled at Faneuil-Hall on Friday the 5th of November Instant, unanimously voted that I the Subscriber was a Distributor of a Paper called the Tradesmen’s Protest—Paxton had that testimony published in the Boston News-Letter and Boston Post-Boy, two Loyalist newspapers, over the following week. He remained unpopular.

Now I solemnly declare, that I never was possessed of more than one of said Papers, which I bought for Three Half-Pence of a Boy in the Street, and not finding it worth Notice, in a few Minutes after I gave it to a Bystander, whom to my Knowledge, I never saw before nor since.—And I further declare, that I never before heard such a Paper was published or intended to be published.

TOMORROW: Talking to the tea consignees.

No comments:

Post a Comment