A Busy Week in Boston in March 1774

Oliver would have taken over certain gubernatorial duties while Hutchinson was out of Massachusetts. But if both men were gone, the executive power would have devolved onto the Council.

That upper house of the Massachusetts General Court hadn’t become as radical as the lower house, but it was still dominated by Hutchinson’s opponents.

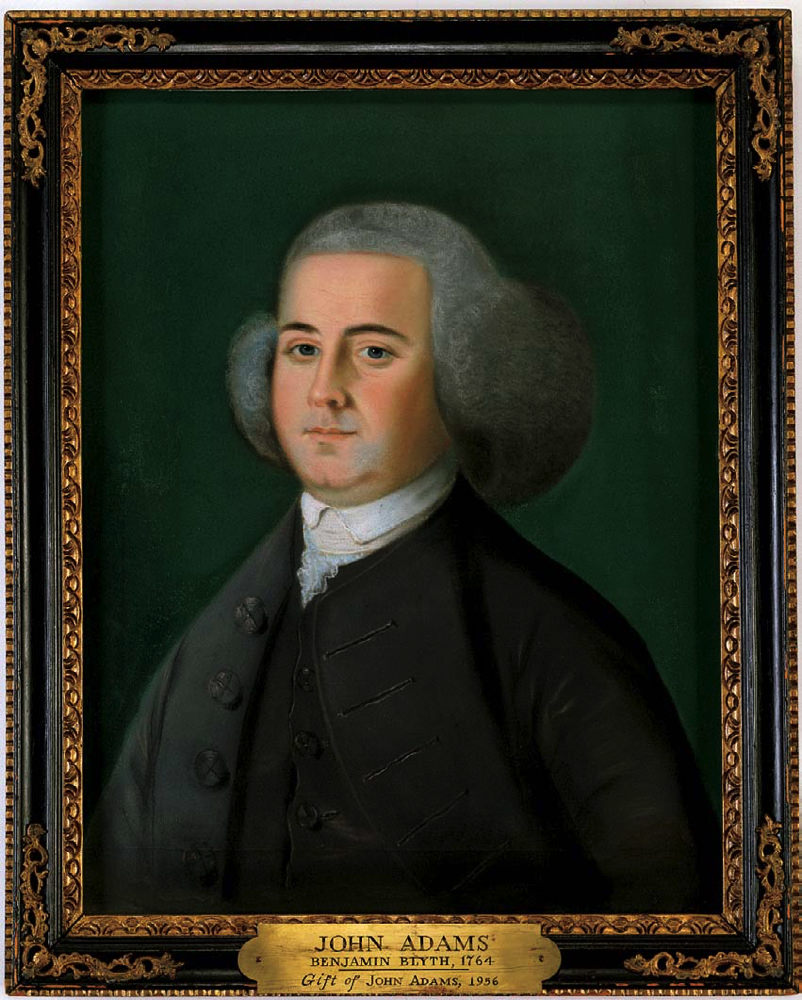

Among those opponents was John Hancock, who on 5 March delivered Boston’s annual oration commemorating the Boston Massacre. This was probably the most politically radical thing he ever did before July 1776.

On Monday, 7 March the house sent a long response to Hutchinson’s message, quoted yesterday, dismissing the effort to impeach Peter Oliver, chief justice and brother of the now late lieutenant governor.

Much of that response was written by Robert Treat Paine of Taunton, as shown by a rough draft in his papers. However, some touches are more political than legal and may have come from Samuel Adams. Most pointedly, the response quoted the phrase “an abridgment of what are called English liberties” from one of Hutchinson’s own leaked letters, which was kind of rubbing it in.

The assembly’s response concluded with yet another complaint about officials like Hutchinson and the Olivers misrepresenting the state of the province:

We assure ourselves, that were the nature of our grievances fully understood by our Sovereign, we should soon have reason to rejoice in the redress of them. But, if we must still be exposed to the continual false representations of persons who get themselves advanced to places of honour and profit by means of such false representations, and when we complain we cannot even be heard, we have yet the pleasure of contemplating, that posterity for whom we are now struggling will do us justice, by abhoring the memory of those men ”who owe their greatness to their country’s ruin.”That last quotation came from Joseph Addison’s Cato.

On the evening of 7 March, men carried out the second Boston Tea Party, dumping twenty-nine crates of tea from the ship Fortune. Some traders had thought that Bostonians would accept that tea since it wasn’t owned by the East India Company. They didn’t.

The funeral for Lt. Gov. Oliver was on 8 March. Prominent members of his family didn’t feel safe attending, and it did not go smoothly.

Meanwhile, there was still a stalemate on impeachment as the legislative session neared a close. On 9 March the house resolved, “it must be presumed that the Governor’s refusing to take any Measures therein is, because he also receives his Support from the Crown.” That same day, Secretary Thomas Flucker brought in Gov. Hutchinson’s message proroguing the legislature until April.

As it turned out, there would be no April session. The impeachment effort was dead.

TOMORROW: In the courtroom.