Museum of African American History Events on the Revolution

The museum website says:

What do you do when a country cries out for liberty—but won’t offer it to you? In the shadowed alleys and crowded docks of Revolutionary-era Boston, Black men and women—enslaved and free—listened as white colonists thundered about freedom. They heard the speeches. They read the broadsides. But they knew: the liberty being shouted from the rooftops was not meant for them. Still, they stepped forward.Those personages include Lucy Terry Prince, Phillis Wheatley Peters, Chloe Spear, and more.

Interact with AI-driven, holographic images of primary sources, and the men and women who represented the African American community in Massachusetts during the period from the 1620s to 1800. Ask questions of the interactive using a voice activated program or by simply typing your queries on a touchscreen.

On Tuesday, 17 February, the museum will host an event called “Digging Deeper into Black Voices of the Revolution.” Chief Curator and Director of Collections Angela Tate and Prof. Nedra Lee will discuss the process of assembling that exhibit. That free event is due to run from 5 to 7 P.M. at the museum on 46 Joy Street. Register to attend here.

On Wednesday, 18 February, the Massachusetts Historical Society will host a panel discussion on the topic “Whose Independence: Black Experiences During the American Revolution.” The panelists will be:

- Dr. Noelle Trent, Museum of African American History | Boston & Nantucket

- Dr. Benjamin Remillard, Providence College

- Dr. Chernoh Sesay Jr., DePaul University

- Dr. Kyera Singleton, Royall House and Slave Quarters

As cries for liberty and clashes with the British broke out in the American colonies, enslaved and free Black people fought for independence on the battlefield, in courtrooms, and their communities. In petitions and writings, they argued that there were contradictions in a fight for freedom that didn’t include a full abolishment of slavery. Following the promise of freedom advertised, many enslaved men enlisted as soldiers. Many joined the Patriot cause while others volunteered with British forces. Throughout the war and in the years following, free Black leaders built the African Lodge and African Meeting House and established spaces for religion and education in their communities.That event will run 6 to 7 P.M. Register to attend in person or online starting at this page.

Back at the Museum of African American History, on Thursday, 26 February, it will host the first U.S. showing of “In Search of Phillis Wheatley Peters,” Leslie Askew’s thirty-five-minute documentary about the poet, her work, new discoveries about her life after marriage, and her cultural legacy. That event is scheduled from 6 to 8 P.M. It is free, with donations welcome. Reserve a space here.

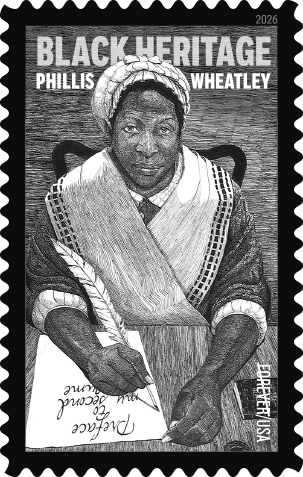

Shown above is the first-class stamp featuring Phillis Wheatley, just issued by the U.S. Postal Service.

.jpg)