“So soon as any coroner shall be certified of the dead body”

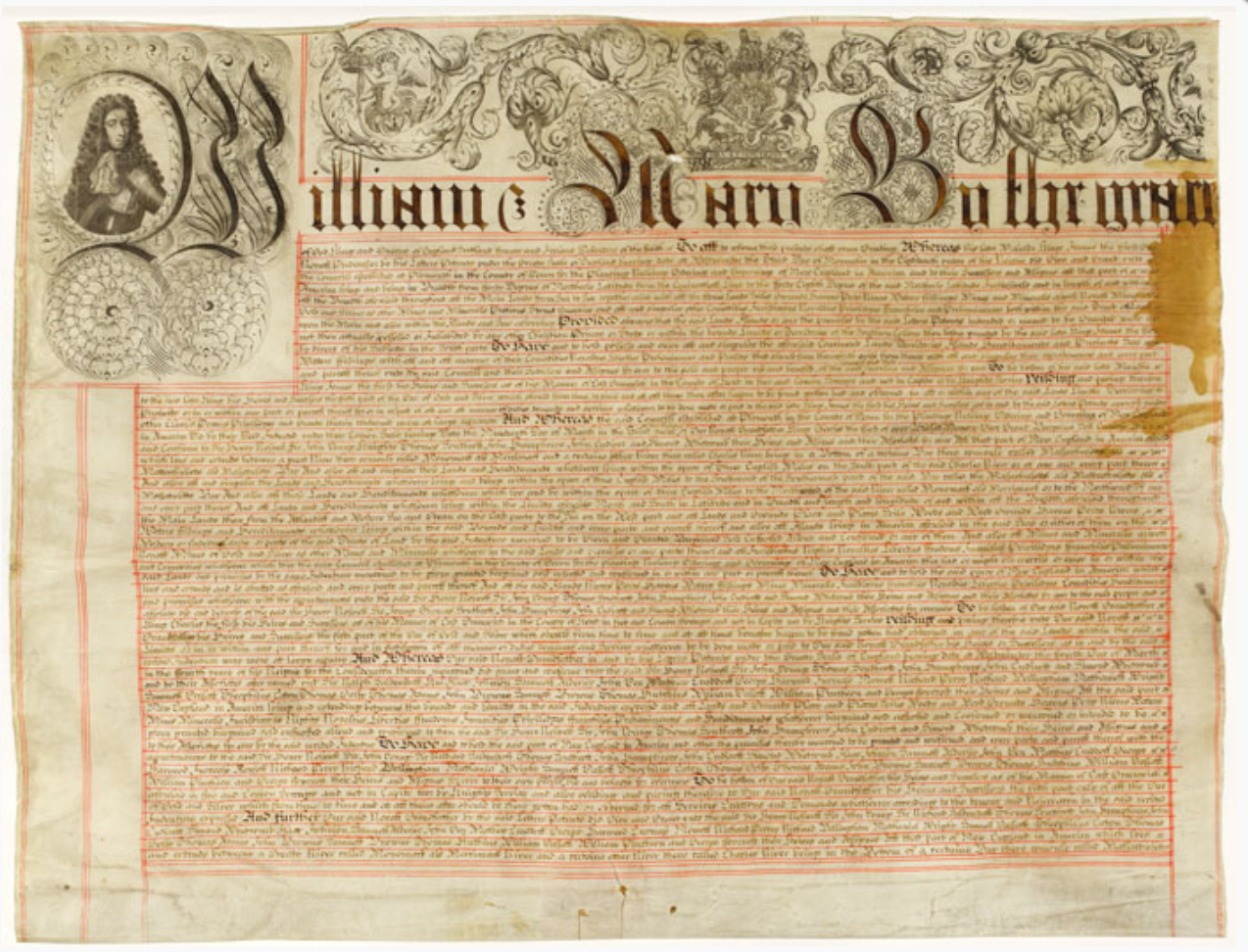

The Pilgrims of the Plymouth Colony established coroners as an elected office in 1636. By the end of the century, however, that colony had been absorbed into the province of Massachusetts Bay, and the monarchs William and Mary had issued a new charter for the province (shown above).

That 1691 charter stipulated:

In 1700 the Massachusetts General Court got around to passing an act on “the office and duty of a coroner.” It stated:

The next section said:

Out of the pool of eighteen men called, the coroner would choose “fourteen or more” for a jury and give them this charge:

The jury findings were specified in such detail that coroners came to use printed forms, filling in the blanks with information about the dead person, the date, the jurors, and so on.

The 1700 law said coroners could collect 10s. per day for travel and expenses, plus 2s. per day for each juror, to be collected from the dead person’s estate (or a dead child’s parents). If not enough money was available, the county treasurer would pay out what was needed.

In 1726 a new law allowed coroners to appoint deputies. In 1739 the legislature decided “some of the coroners within this province have of late greatly multiplied their deputies, and under colour of such deputation persons have pretended to be exempted from duties,” so it made such deputies a temporary appointment.

In contrast, coroners, like justices of the peace, kept their jobs for life—but that meant either their own lifespan, or the lifespan of the monarch under whom they were appointed.

COMING UP: Up for renewal.

That 1691 charter stipulated:

it shall and may be lawfull for the said Governour with the advice and consent of the Councill or Assistants from time to time to nominate and appoint Judges Commissioners of Oyer and Terminer Sheriffs Provosts Marshalls Justices of the Peace and other Officers to Our Councill and Courts of Justice belonging…The charter didn’t mention coroners, but everyone probably assumed they fell within the “other Officers” category. Such officials had presided over inquests in England for centuries, and in Massachusetts for decades. The big difference was that now the royal governor of Massachusetts, appointed by the ministry in London, would name coroners in every county, subject to the consent of the Council.

In 1700 the Massachusetts General Court got around to passing an act on “the office and duty of a coroner.” It stated:

every coroner, within the county for which he is appointed, shall be, and hereby is empowered to take inquests of felonies, and other violent and casual deaths committed, or happening within his precinct.The law then devoted many more words to spelling out the oath that coroners would swear.

The next section said:

when and so soon as any coroner shall be certified of the dead body of any person supposed to have come to a violent and untimely death, found or lying within his county or precinct, he shall make out his warrant directed unto the constables of the same town where such dead body lies, or of three or four of the next adjacent towns, if need be, requiring them forthwith to summon a jury of good and lawful men of the same town, or such number as shall be sufficient, with those sent for from the neighbouring towns to make up eighteen in all, to appear before him at the time and place in the said warrant expressedThen the law specified the language of the summons, the oath for the jury foreman chosen by the coroner, the oath for those jurors, and the fines to be levied if the constables or prospective jurors didn’t do their duties. I’m pleased to report that the law let the coroner swear in jurors “by three or four at once,” or else we’d still be waiting.

Out of the pool of eighteen men called, the coroner would choose “fourteen or more” for a jury and give them this charge:

You shall diligently inquire, and true presentment make, on the behalf of our sovereign lord the king, how and in what manner A. B. here lying dead, came to his death; and you shall deliver up to me, his majesty’s coroner, a true verdict thereof, according to such evidence as shall be given to you, and according to your knowledge. . . .Coroners could also summon witnesses, and of course they had their own oaths to swear.

to declare of the death of the person, whether he died of felony, or by mischance and accident? and if of felony, whether of his own or of another’s? and if by mischance or misfortune, whether by the act of God or of man? and if he died of another’s felony, who were principals and who accessaries? who threatened him of his life or members? with what instrument he was struck or wounded? and so of all prevailing circumstances that can come by presumption.

And if by mischance or accident, by the act of God or man, whether by hurt, fall, stroke, drowning, or otherwise, to inquire of the persons that were present, the finders of the body, his relations or neighbours, whether he was killed in the same place, or elsewhere? and if elsewhere, by whom and how he was thence brought? and of all other circumstances.

And if he died of his own felony, then to inquire of the manner, means or instrument, and circumstances concurring.

The jury findings were specified in such detail that coroners came to use printed forms, filling in the blanks with information about the dead person, the date, the jurors, and so on.

The 1700 law said coroners could collect 10s. per day for travel and expenses, plus 2s. per day for each juror, to be collected from the dead person’s estate (or a dead child’s parents). If not enough money was available, the county treasurer would pay out what was needed.

In 1726 a new law allowed coroners to appoint deputies. In 1739 the legislature decided “some of the coroners within this province have of late greatly multiplied their deputies, and under colour of such deputation persons have pretended to be exempted from duties,” so it made such deputies a temporary appointment.

In contrast, coroners, like justices of the peace, kept their jobs for life—but that meant either their own lifespan, or the lifespan of the monarch under whom they were appointed.

COMING UP: Up for renewal.

No comments:

Post a Comment