Whatever Happened to James Marr?

As quoted yesterday, in 1835 the Revolutionary War veteran Thaddeus Blood told Ralph Waldo Emerson that he doubted the deposition published over the name of Pvt. John Bateman really came from that prisoner.

Bateman, Blood said, was too badly injured on 19 Apr 1775 to give testimony. He believed instead that “It was probably Carr’s or Starr’s deposition.” But there’s no one named Carr or Starr in this story.

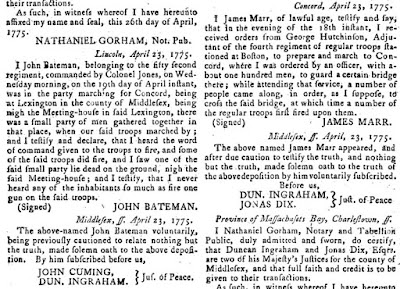

There was, however, a Pvt. James Marr, another British soldier captured on the first day of the war and held in Concord. Marr also gave a deposition to provincial magistrates and spoke to the Rev. William Gordon. I suspect Blood remembered that man but not exactly.

Blood saw Bateman’s deposition reprinted in “Dr. R’s History”—A History of the Fight at Concord, by the Rev. Dr. Ezra Ripley, first published in 1827. Blood knew Ripley well; the minister provided a character reference when the veteran applied for a pension.

Ripley’s book focused on whether the Lexington militiamen had fired back at the redcoats on 19 April in some significant way. It did not cite or reprint James Marr’s deposition, which was about the fight at the North Bridge.

Bateman thus had no reminder about Marr’s name in front of him. He also didn’t see how every time Patriots recorded Bateman’s testimony in 1775, they took down Marr’s testimony the same day. In other words, there was no motive for them to put Marr’s words into Bateman’s mouth since it would have been easier just to credit those words to Marr.

Blood had a vivid memory of Bateman when he was dying in Concord; “his wounds stunk intolerably,” the old man recalled sixty years later. But before the infection set in, Bateman was probably well enough to testify. Blood also must have remembered Marr, but less exactly, as a cooperative prisoner, the kind who would give testimony against his own army. Why would Blood recall Marr that way?

One clue appears in Lemuel Shattuck’s history of Concord, published the same year that Blood spoke to Emerson. Shattuck listed a James Marr among the men from Middlesex County whom Col. James Barrett enrolled in the Continental Army for three years starting in January 1777.

This may be the same James Marr(s) who is recorded as serving during the 1780s out of Groton, according to documents transcribed in Samuel Abbott Green’s Groton During the Revolution. Volume 25 of the Proceedings of the Worcester Society of Antiquity likewise lists James Marr in Capt. Sylvanus Smith’s company but doesn’t state a home town.

Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War puts James Marr of Groton in Capt. Sylvanus Smith’s company, Col. Timothy Bigelow’s regiment. He was 5'9" tall and turned 24 years old at the end of 1780, which would make him 18 when the war began. This Marr was even promoted to sergeant. But his name never appeared in the Groton vital records, and there’s no clue about where he settled after the war.

To be sure, the James Marr from Groton might not have been the former prisoner. (There was at least one other James Marr from Massachusetts serving in the Continental Army, a man from Scarborough and Limington, Maine.) But I suspect the James Marr who cooperated with the provincials in April 1775 did even more cooperating in the years that followed.

No comments:

Post a Comment