Pickering on the Beginning of the Siege

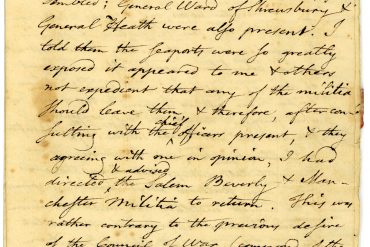

Earlier this week the Journal of the American Revolution made the first publication of a 21 Apr 1775 letter by Timothy Pickering, colonel of the Essex County militia. The letter now belongs to the Harlan Crow Library in Dallas.

The title of library curator Samuel Fore’s article emphasizes Pickering as an “Eyewitness to the British Retreat from Lexington.” However, the letter doesn’t say anything about the events of 19 April (including Pickering’s own actions, which were controversial for decades).

Rather, on 21 April Pickering wrote about how the siege of Boston was taking shape. Or at least about the situation on the northern wing of the siege; he didn’t mention what was going on in Roxbury at all. Instead, he told a colleague from Essex County:

As a regimental commander, Pickering was invited to a council of war in Cambridge headed by Gen. Artemas Ward and Gen. William Heath, with Dr. Joseph Warren sitting in. Characteristically, Pickering voiced his opinions, including on whether the Massachusetts troops should attack the British positions:

Another question the Massachusetts commanders faced was whether to maintain maximum forces around Boston or send some militia units back home to defend their coastal towns from possible attack by the Royal Navy. Pickering didn’t want to leave Salem undefended:

Toward the end of his letter, Pickering wrote: “I have also just heard by a man from Boston, that Earl Percy is badly if not dangerously wounded.” That rumor was false. Lt. Col. Francis Smith had been wounded, though not badly, but Col. Percy was unhurt.

The title of library curator Samuel Fore’s article emphasizes Pickering as an “Eyewitness to the British Retreat from Lexington.” However, the letter doesn’t say anything about the events of 19 April (including Pickering’s own actions, which were controversial for decades).

Rather, on 21 April Pickering wrote about how the siege of Boston was taking shape. Or at least about the situation on the northern wing of the siege; he didn’t mention what was going on in Roxbury at all. Instead, he told a colleague from Essex County:

The regulars were entrenching on the first hill beyond Charlestown neck; also on a point of ground (as well as I could learn) in Cambridge river, just as it opens to the Bay. For what purposes I cannot tell, but conjecture to prevent the provincials entering Boston by the way of Charlestown, or by boats going down Cambridge river. The provincials, perhaps three or four thousand men, were scattered about Cambridge common too much at random.Lack of discipline by the common soldier was a fairly constant theme in Pickering’s military writings.

As a regimental commander, Pickering was invited to a council of war in Cambridge headed by Gen. Artemas Ward and Gen. William Heath, with Dr. Joseph Warren sitting in. Characteristically, Pickering voiced his opinions, including on whether the Massachusetts troops should attack the British positions:

I ventured to declare my opinion “That we ought to act only on the defensive; but some thought that now was the time to strike, & that now the day might be our own, & end the dispute. I could not think so: for besides the scanty portion of ammunition we at present could come at, our men were not sufficiently prepared for action; they were not disciplined even for an irregular engagement; few, very few, have had experience; & the officers in general have neither instructed themselves nor men how to act: The confusions of yesterday, testified by every officer I could talk with, fully justify these assertions. . . .That reinforces Pickering’s reputation for wanting to find an “accommodation” with the royal government when other Massachusetts Patriots were ready to push harder. People groused that his attitude had kept the Essex County troops from engaging with the British column on 19 April.

Another & what appeared to me an important reason for acting only on the defensive was this. The attack is universally said by our people to have been begun by the King’s troops: This may serve to justify a return of fire from us; and tho by pursuing them we seemed to act offensively, yet that was a natural consequence of the first attack, & might be excused: but to attack the troops, while they remained, as now, quiet in the trenches, would be deemed a much more atrocious act, & fatally prevent an accommodation, which notwithstanding yesterday’s skirmish, did not appear wholly impracticable.[”]

Another question the Massachusetts commanders faced was whether to maintain maximum forces around Boston or send some militia units back home to defend their coastal towns from possible attack by the Royal Navy. Pickering didn’t want to leave Salem undefended:

I told them the seaports were so greatly exposed it appeared to me & others not expedient that any of the militia should leave them, & therefore, after consulting with the chief officers present I had directed and advised the Salem, Beverly, and Manchester militia to return. This was rather contrary to the previous desire of the Council of War, (composed of the General & field officers above mentioned;) but afterwards it appeared that they also judged it expedient, by directing the Ipswich companies to return:That shows us how loose Gen. Ward’s authority was. The previous day’s council of war had agreed to keep troops at the siege lines, but Pickering had already sent some of his men home.

Toward the end of his letter, Pickering wrote: “I have also just heard by a man from Boston, that Earl Percy is badly if not dangerously wounded.” That rumor was false. Lt. Col. Francis Smith had been wounded, though not badly, but Col. Percy was unhurt.

No comments:

Post a Comment