“A Day which ought to be forever remembered in America”

Earlier this month I posited that the American Revolution began on 14 Aug 1765 with the earliest public protest against the Stamp Act, the first step in turning a debate among legislatures into a continent-wide mass movement.

After the riots on 26 August, culminating in the destruction of Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s house, the Boston Whigs had a strong motive to focus public memory on that first date so they could disavow what happened on the second.

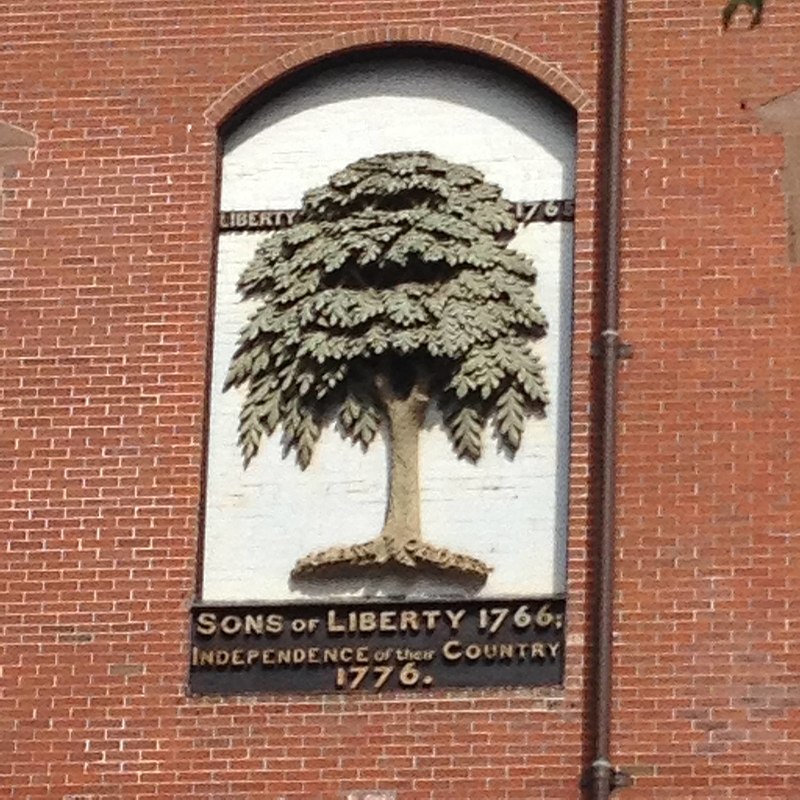

Those Sons of Liberty decorated Liberty Tree in the South End with a plaque and that famous name. [Don’t think about what happened in the North End!] They held banquets on the anniversary of the first protest. [Don’t remember the second!] They kept the ritual of hanging political enemies in effigy, but no houses were damaged as badly as Hutchinson’s before the outbreak of war.

On 19 Aug 1771, the Boston Gazette published a front-page article signed “Candidus,” which politically minded Bostonians recognized to be Samuel Adams. He said:

In 1771, however, the town of Boston began to make a bigger deal of the 5th of March, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Then at the end of the Revolutionary War, the town switched its annual oration to the 4th of July, a date with undoubted national significance.

In the early 1800s retired President John Adams helped to shape the memory of the early Revolution by sharing recollections in letters and by encouraging William Tudor, Jr., to write a biography of James Otis, Jr. As I discussed way back here, Adams was responding to William Wirt’s biography of Patrick Henry, which credited a Virginian with kicking off the Stamp Act protest movement.

And in an important way, that’s what Patrick Henry did in the Virginia House of Burgesses. And exaggerated reports of Patrick Henry’s proposals did even more. Those newspaper reports probably emboldened the Loyall Nine in Boston.

Adams, who called himself “jealous, very jealous, of the honour of Massachusetts,” wanted Americans to see his home state as a leader in the resistance to London, not just a close follower. He pointed to Otis’s arguments in the 1761 writs of assistance case in these terms: “Then and there was the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born.” That pushed the start of the American Revolution back.

I’m not won over by Adams’s position. Otis’s argument was unsuccessful and got limited press coverage outside of Massachusetts, where the legal decision didn’t apply anyway. Like Henry’s resolutions, the writs of assistance case was a protest from upper-class men inside exclusive chambers working through official channels. It wasn’t revolutionary.

After the riots on 26 August, culminating in the destruction of Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s house, the Boston Whigs had a strong motive to focus public memory on that first date so they could disavow what happened on the second.

Those Sons of Liberty decorated Liberty Tree in the South End with a plaque and that famous name. [Don’t think about what happened in the North End!] They held banquets on the anniversary of the first protest. [Don’t remember the second!] They kept the ritual of hanging political enemies in effigy, but no houses were damaged as badly as Hutchinson’s before the outbreak of war.

On 19 Aug 1771, the Boston Gazette published a front-page article signed “Candidus,” which politically minded Bostonians recognized to be Samuel Adams. He said:

The Sons of Liberty on the 14th of August 1765, a Day which ought to be forever remembered in America, animated with a zeal for their country then upon the brink of destruction, and resolved, at once to save her, or like Samson, to perish in the ruins, exerted themselves with such distinguished vigor, as made the house of Dagon to shake from its very foundation; and the hopes of the lords of the Philistines even while their hearts were merry, and when they were anticipating the joy of plundering this continent, were at that very time buried in the pit they had digged.Basically my argument about the significance of that date is the same, with fewer scriptural allusions.

The People shouted; and their shout was heard to the distant end of this Continent. In each Colony they deliberated and resolved, and every Stampman trembled; and swore by his Maker, that he would never execute a commission which he had so infamously received.

In 1771, however, the town of Boston began to make a bigger deal of the 5th of March, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Then at the end of the Revolutionary War, the town switched its annual oration to the 4th of July, a date with undoubted national significance.

In the early 1800s retired President John Adams helped to shape the memory of the early Revolution by sharing recollections in letters and by encouraging William Tudor, Jr., to write a biography of James Otis, Jr. As I discussed way back here, Adams was responding to William Wirt’s biography of Patrick Henry, which credited a Virginian with kicking off the Stamp Act protest movement.

And in an important way, that’s what Patrick Henry did in the Virginia House of Burgesses. And exaggerated reports of Patrick Henry’s proposals did even more. Those newspaper reports probably emboldened the Loyall Nine in Boston.

Adams, who called himself “jealous, very jealous, of the honour of Massachusetts,” wanted Americans to see his home state as a leader in the resistance to London, not just a close follower. He pointed to Otis’s arguments in the 1761 writs of assistance case in these terms: “Then and there was the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born.” That pushed the start of the American Revolution back.

I’m not won over by Adams’s position. Otis’s argument was unsuccessful and got limited press coverage outside of Massachusetts, where the legal decision didn’t apply anyway. Like Henry’s resolutions, the writs of assistance case was a protest from upper-class men inside exclusive chambers working through official channels. It wasn’t revolutionary.

No comments:

Post a Comment