The Landlord of Liberty Tree

This is how the merchant John Rowe described Boston’s first public protest against the Stamp Act in his diary:

As far back as May 1733, when the Boston town meeting debated setting up official marketplaces, one of the proposed sites was “near the great Tree, at the South-End, near Mr. Eliot’s House.” When the 31 May Boston News-Letter reported on that hotly contested vote (364 yeas to 339 nays), it referred to “the great Trees at the South End.” That phrase suggests that there were multiple large trees near Eliot’s house, but one particularly big one. It had probably been growing there for over a century, since before Englishmen came to the Shawmut peninsula.

As for clues about “Deacon Elliot,” this advertisement appeared in the 17 June 1734 New-England Weekly Journal:

John Eliot was born in 1692, a descendant of some of Boston’s earliest British settlers. He was a great-nephew of the famous Rev. John Eliot, “Apostle to the Indians.” The young man appears to have followed his uncle Benjamin Eliot (1665-1741) into the business of bookbinding and stationery sales. He also commissioned small books from printers, almost all sermons and other religious literature. As early as 1716 Eliot was issuing these publications “at his shop at the south-end.”

It appears Eliot inherited that land in the South End, as well as property out in Brookline. In 1708, when the Boston selectmen laid out the southernmost stretch of the main road through town, they defined Orange Street as from the old Neck fortifications to the Eliot house. With, presumably, the great elms nearby.

As he neared the age of thirty, Eliot married Sarah Holyoke. Her brother, the Rev. Edward Holyoke, was a Marblehead minister who became president of Harvard College. The Eliots had eight children between 1721 and 1735.

In the early decades of the eighteenth century, the south end of Boston was still sparsely populated. Then the Hollis Street Meetinghouse was built for the Rev. Mather Byles in 1732. The town opened its south market, and soon the area had more houses and streets. We can see that growth in how Eliot’s title pages described his business:

Deacon Eliot’s big trees remained a handy landmark for people entering or navigating town. Newspaper advertisements tell us Josiah Quincy, Sr., lived “opposite to the great Trees, at the South End,” until he struck it rich in privateering and moved to a country estate in Braintree. Other sites in the neighborhood included the house of auctioneer and deacon Benjamin Church, Sr.; the leather workshop of Adam Colson; and a building once called “the Half-Moon, or Land-Bank House.”

Isaiah Thomas later wrote of Eliot:

Sarah Eliot died in 1755 at the age of sixty. Deacon John Eliot was then sixty-three years old. He married again to a woman named Mary, then in her forties, but she died in 1761. The deacon’s daughters Sarah and Silence remained unmarried, so one or both might have kept house for him after that.

In August 1765, as described yesterday, the Loyall Nine used the boughs of Deacon Eliot’s tree to hang Andrew Oliver in effigy. The figures of several other royal appointees and political enemies followed in the subsequent years. The Sons of Liberty put up a flagpole beside the tree and raised a banner—the Union Jack on a red field—to call public gatherings. Christopher Seider’s funeral train stopped at the tree. So did the processions of men being tarred and feathered.

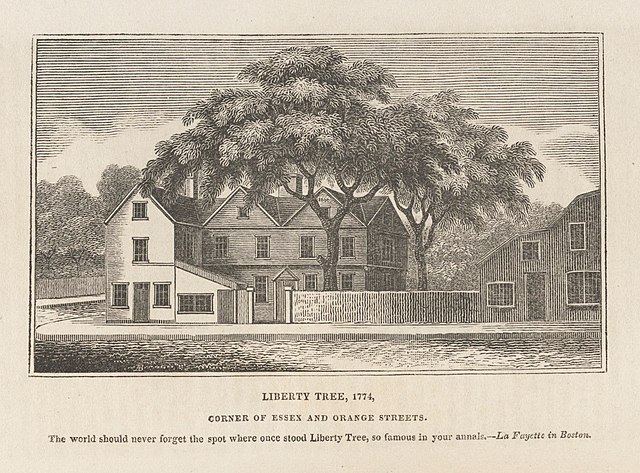

The way people referred to the tree as belonging to Deacon Eliot suggests it stood on his property with the branches extending over the street. It’s not clear how near Eliot’s house was to the tree, or whether he had a fence around his land. (The picture above was created decades after the tree was cut down in 1775, and there’s no way to know how accurate it was.) How did Eliot feel about the large political gatherings right outside his house? About his property being identified with rebellion?

Though Eliot doesn’t show up on the records as an active Whig, he does seem to have supported that cause and accepted the new identity for the elm outside his house. The 10 Apr 1769 Boston Gazette included an advertisement saying that land and “a large Building thereon, commonly known by the Name of the South Market,” was to be sold by court order. Prospective buyers were invited to “inquire of John Eliot at Liberty-Tree.”

On 14 August that year, the elderly deacon was among the many local dignitaries who dined with Boston’s Sons of Liberty at Lemuel Robinson’s tavern in Dorchester. In 1770, when William Billings advertised his New-England Psalm-Singer, one of the of the four places where people could buy it was “Deacon Elliot’s under Liberty-Tree.”

By that time, Deacon Eliot was in his late seventies. He didn’t live to see all that his elm tree inspired. On 22 Nov 1771, the Boston News-Letter ran this death notice:

The gravestone for Deacon John Eliot and his two wives still stands in the Granary Burying Ground.

A Great Number of people assembled at Deacon Elliots Corner this morning to see the Stamp Officer hung in Effigy with a Libel on the Breast, on Deacon Elliot’s tree…The great elm that held the effigy and provided shade for that protest hadn’t yet been dubbed Liberty Tree. In the coming months, the Sons of Liberty would come up with that name, hammer a plaque into the side of the tree, and make it a political gathering-point. As of mid-August 1765, however, that elm was still “Deacon Elliot’s tree.” And who was he?

As far back as May 1733, when the Boston town meeting debated setting up official marketplaces, one of the proposed sites was “near the great Tree, at the South-End, near Mr. Eliot’s House.” When the 31 May Boston News-Letter reported on that hotly contested vote (364 yeas to 339 nays), it referred to “the great Trees at the South End.” That phrase suggests that there were multiple large trees near Eliot’s house, but one particularly big one. It had probably been growing there for over a century, since before Englishmen came to the Shawmut peninsula.

As for clues about “Deacon Elliot,” this advertisement appeared in the 17 June 1734 New-England Weekly Journal:

TO BE LETT,When proposals for publishing an American Magazine went around in 1743, “Mr. John Eliot, at the great Trees at the South-End,” was one of the men collecting subscriptions (along with “Mr. Benja. Franklin, Post Master in Philadelphia”).

A Good convenient House, adjoyning the South Market place, with a large Garden in good Order; Inquire of Mr. John Eliot Stationer, living near the great Trees.

John Eliot was born in 1692, a descendant of some of Boston’s earliest British settlers. He was a great-nephew of the famous Rev. John Eliot, “Apostle to the Indians.” The young man appears to have followed his uncle Benjamin Eliot (1665-1741) into the business of bookbinding and stationery sales. He also commissioned small books from printers, almost all sermons and other religious literature. As early as 1716 Eliot was issuing these publications “at his shop at the south-end.”

It appears Eliot inherited that land in the South End, as well as property out in Brookline. In 1708, when the Boston selectmen laid out the southernmost stretch of the main road through town, they defined Orange Street as from the old Neck fortifications to the Eliot house. With, presumably, the great elms nearby.

As he neared the age of thirty, Eliot married Sarah Holyoke. Her brother, the Rev. Edward Holyoke, was a Marblehead minister who became president of Harvard College. The Eliots had eight children between 1721 and 1735.

In the early decades of the eighteenth century, the south end of Boston was still sparsely populated. Then the Hollis Street Meetinghouse was built for the Rev. Mather Byles in 1732. The town opened its south market, and soon the area had more houses and streets. We can see that growth in how Eliot’s title pages described his business:

- “at his shop, the south end of the town,” 1724

- “in Orange Street at the south end of the town,” 1734

- “near the South Market,” 1741

Deacon Eliot’s big trees remained a handy landmark for people entering or navigating town. Newspaper advertisements tell us Josiah Quincy, Sr., lived “opposite to the great Trees, at the South End,” until he struck it rich in privateering and moved to a country estate in Braintree. Other sites in the neighborhood included the house of auctioneer and deacon Benjamin Church, Sr.; the leather workshop of Adam Colson; and a building once called “the Half-Moon, or Land-Bank House.”

Isaiah Thomas later wrote of Eliot:

He published a few books, and was, many years, a bookseller and binder, but his concerns were not extensive. However, he acquired some property; and being a respectable man, was made deacon of the church in Hollis street.Thomas simply missed the period when Eliot was most active in publishing. After his uncle’s death in 1741, the deacon appears to have cut back on new ventures and lived off his real estate and shop.

Sarah Eliot died in 1755 at the age of sixty. Deacon John Eliot was then sixty-three years old. He married again to a woman named Mary, then in her forties, but she died in 1761. The deacon’s daughters Sarah and Silence remained unmarried, so one or both might have kept house for him after that.

In August 1765, as described yesterday, the Loyall Nine used the boughs of Deacon Eliot’s tree to hang Andrew Oliver in effigy. The figures of several other royal appointees and political enemies followed in the subsequent years. The Sons of Liberty put up a flagpole beside the tree and raised a banner—the Union Jack on a red field—to call public gatherings. Christopher Seider’s funeral train stopped at the tree. So did the processions of men being tarred and feathered.

The way people referred to the tree as belonging to Deacon Eliot suggests it stood on his property with the branches extending over the street. It’s not clear how near Eliot’s house was to the tree, or whether he had a fence around his land. (The picture above was created decades after the tree was cut down in 1775, and there’s no way to know how accurate it was.) How did Eliot feel about the large political gatherings right outside his house? About his property being identified with rebellion?

Though Eliot doesn’t show up on the records as an active Whig, he does seem to have supported that cause and accepted the new identity for the elm outside his house. The 10 Apr 1769 Boston Gazette included an advertisement saying that land and “a large Building thereon, commonly known by the Name of the South Market,” was to be sold by court order. Prospective buyers were invited to “inquire of John Eliot at Liberty-Tree.”

On 14 August that year, the elderly deacon was among the many local dignitaries who dined with Boston’s Sons of Liberty at Lemuel Robinson’s tavern in Dorchester. In 1770, when William Billings advertised his New-England Psalm-Singer, one of the of the four places where people could buy it was “Deacon Elliot’s under Liberty-Tree.”

By that time, Deacon Eliot was in his late seventies. He didn’t live to see all that his elm tree inspired. On 22 Nov 1771, the Boston News-Letter ran this death notice:

Last Thursday died here, Mr. John Eliot, Deacon of the Church under the Pastoral Care of the the Rev’d Dr. Byles—He justly sustain’d the Character of an Honest Man, and a good Christian—His Remains were decently interr’d on Saturday last.Three days later an ad in the Boston Gazette called on people with debts to settle with Eliot’s estate to meet with the administrators, Joseph Eliot and Thomas Crafts, Jr. The former was probably his son (1727-1782), who moved to Natick, as did his unmarried sisters. The latter was a member of the Loyall Nine who watched over Liberty Tree from his nearby workshop.

The gravestone for Deacon John Eliot and his two wives still stands in the Granary Burying Ground.

2 comments:

I had always heard that Liberty Tree was next to a tavern; but I don't see any mention of that here. Was my assumption incorrect?

Liberty Tree was near Chase and Speakman’s distillery, where the Loyall Nine met. But the nearest prominent tavern appears to have been the Sign of the White Horse, which I don’t think neighbored the site.

In 1769 the Boston Sons of Liberty dined at a tavern named after the Liberty Tree in Dorchester, which could be another source of this link.

Post a Comment