Examining a Copy of an Almanac for 1737

I enjoyed reading Renée Wolcott’s essay on investigating a copy of Poor Richard’s Almanac from 1737, recently shared by the American Philosophical Society, where she’s Assistant Head of Conservation.

In 1923 a collector of material on Benjamin Franklin gave this copy of the 1737 alamanac to the society. Unlike most almanacs, which were utilitarian ephemera, this one showed very little damage to its edges. To the naked eye, it looked complete and well preserved.

However, a note with the copy said that the title page and a later page were “in facsimile,” meaning that they had been reproduced.

After a display this spring, Wolcott decided to look more closely at that pamphlet. She started by examining the pages under ultraviolet light. The wide page margins, and all or part of those two designated pages, glowed differently from the paper under the central text.

Next she evaluated light shone through the paper. That revealed different fiber structure in those parts of the pages.

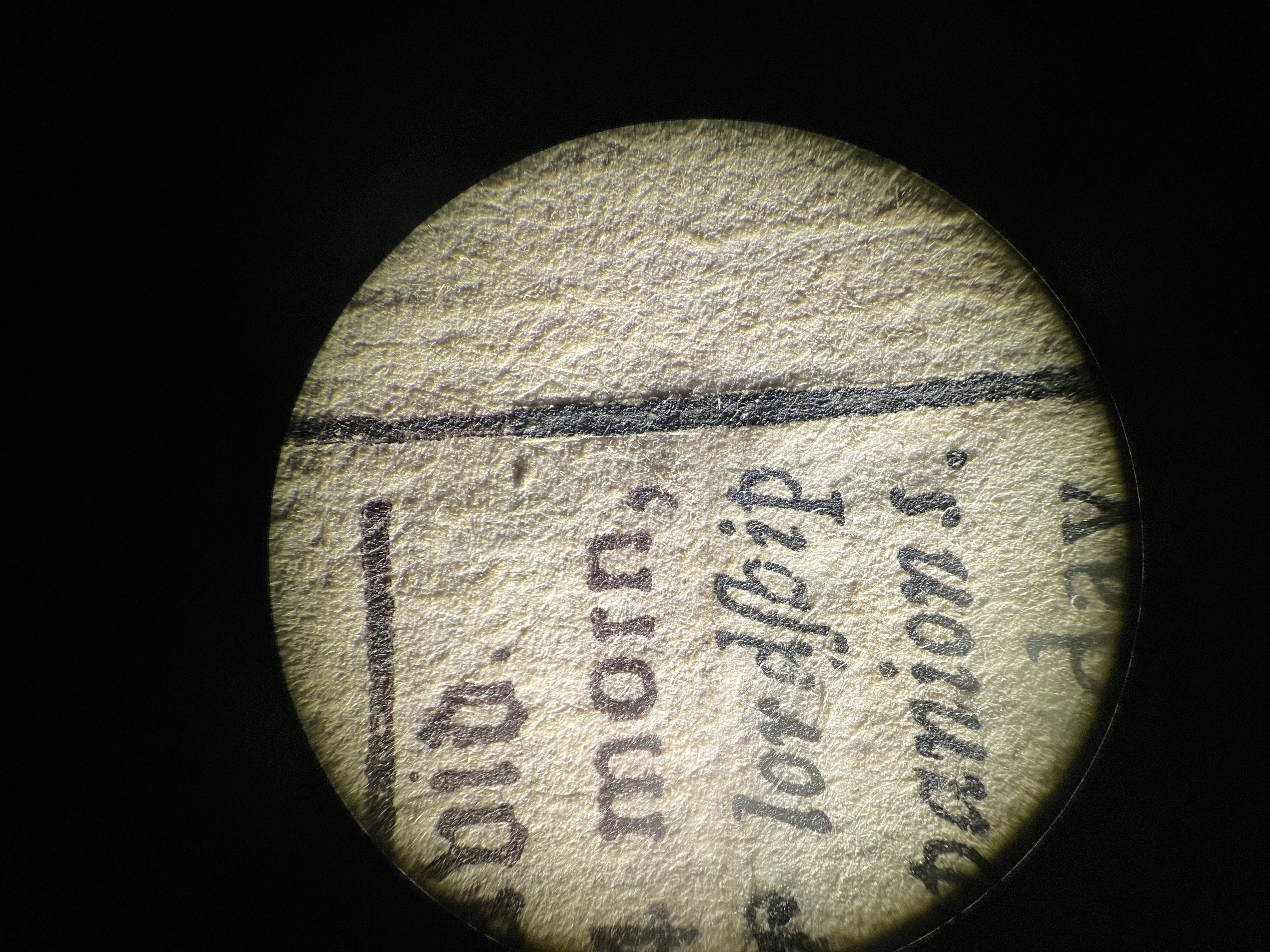

Finally, with a strong microscope and a raking light, Wolcott could spot the borders where “old and new papers were beveled with a knife, overlapped, and adhered together” to make what appeared to be an intact original page. That magnification also showed the ink in the newer portion of the page to be slightly more purple than the original.

Wolcott thus confirmed that the two pages in this Poor Richard’s for 1737 labeled as facsimiles were indeed reproductions in whole or part, and also that the margins of the other pages had been augmented, though nothing was printed on them.

Since the main alterations were disclosed and the almanac donated, this work wasn’t done to deceive but to make the artifact look as handsome and complete as possible.

Check out Wolcott’s essay for more detail and photographs of the crucial evidence.

In 1923 a collector of material on Benjamin Franklin gave this copy of the 1737 alamanac to the society. Unlike most almanacs, which were utilitarian ephemera, this one showed very little damage to its edges. To the naked eye, it looked complete and well preserved.

However, a note with the copy said that the title page and a later page were “in facsimile,” meaning that they had been reproduced.

After a display this spring, Wolcott decided to look more closely at that pamphlet. She started by examining the pages under ultraviolet light. The wide page margins, and all or part of those two designated pages, glowed differently from the paper under the central text.

Next she evaluated light shone through the paper. That revealed different fiber structure in those parts of the pages.

Finally, with a strong microscope and a raking light, Wolcott could spot the borders where “old and new papers were beveled with a knife, overlapped, and adhered together” to make what appeared to be an intact original page. That magnification also showed the ink in the newer portion of the page to be slightly more purple than the original.

Wolcott thus confirmed that the two pages in this Poor Richard’s for 1737 labeled as facsimiles were indeed reproductions in whole or part, and also that the margins of the other pages had been augmented, though nothing was printed on them.

Since the main alterations were disclosed and the almanac donated, this work wasn’t done to deceive but to make the artifact look as handsome and complete as possible.

Check out Wolcott’s essay for more detail and photographs of the crucial evidence.

No comments:

Post a Comment