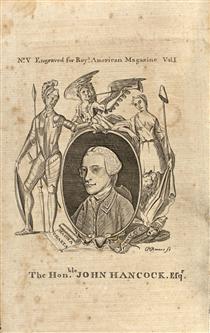

Hancock and the First Continental Congress

Sometime in early June 1774, as I discussed yesterday, John Hancock became sick.

That month he was not in evidence at Salem during the sitting of the Massachusetts General Court.

The main business of that legislative session, as I recounted in June, was to choose delegates to the new Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

Hancock’s absence, and the fact that his colleagues understood him to be seriously ill, help to explain why he wasn’t selected as one of Massachusetts’s delegates.

Later in his career, Hancock gained a reputation for claiming illness when he faced a political task he’d rather not tackle.

But with Hancock home sick, the General Court chose a delegation of “the Hon. James Bowdoin, Esq; the Hon. Thomas Cushing, Esq; Mr. Samuel Adams, John Adams, Esq; and Robert Treat Paine, Esq”.

Of that group, Bowdoin and Cushing had the same profile as Hancock: wealthy, educated, well-mannered Boston merchants who were spending most of their time on politics. Those two men were older and higher-ranking in government, however. So it’s conceivable that Hancock would have been left off this list anyway, in favor of men with more seniority.

But then Bowdoin decided he couldn’t go.

TOMORROW: An opening?

That month he was not in evidence at Salem during the sitting of the Massachusetts General Court.

The main business of that legislative session, as I recounted in June, was to choose delegates to the new Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

Hancock’s absence, and the fact that his colleagues understood him to be seriously ill, help to explain why he wasn’t selected as one of Massachusetts’s delegates.

Later in his career, Hancock gained a reputation for claiming illness when he faced a political task he’d rather not tackle.

- He was too ill to remain as governor when the post-war debt crisis was hitting western Massachusetts farmers (but happily returned to that office after the Shays Rebellion was over).

- He was too ill to attend most of Massachusetts’s convention on ratifying the U.S. Constitution (until he could enter with a crucial speech supporting the document with changes).

- He was too ill to wait on President George Washington in Boston (though eventually he was dramatically carried into that meeting).

But with Hancock home sick, the General Court chose a delegation of “the Hon. James Bowdoin, Esq; the Hon. Thomas Cushing, Esq; Mr. Samuel Adams, John Adams, Esq; and Robert Treat Paine, Esq”.

Of that group, Bowdoin and Cushing had the same profile as Hancock: wealthy, educated, well-mannered Boston merchants who were spending most of their time on politics. Those two men were older and higher-ranking in government, however. So it’s conceivable that Hancock would have been left off this list anyway, in favor of men with more seniority.

But then Bowdoin decided he couldn’t go.

TOMORROW: An opening?

No comments:

Post a Comment