Picking at the Martha Washington Dress Quilt

In the Colonial Revival period, many Americans came forward with relics of the Revolution passed down in their families or discovered in attics.

And some of those were even authentic.

Others, however, were not. I retold the saga of a reputed Thomas Oliver portrait here, for example.

Among items donated to the Bostonian Society in its early decades, I’m skeptical about the machine-woven “Sons of Liberty flag.”

I worked with Dave Ingram on a report about a powder horn ascribed to Richard Gridley; we determined it was almost certainly a Colonial Revival–era creation.

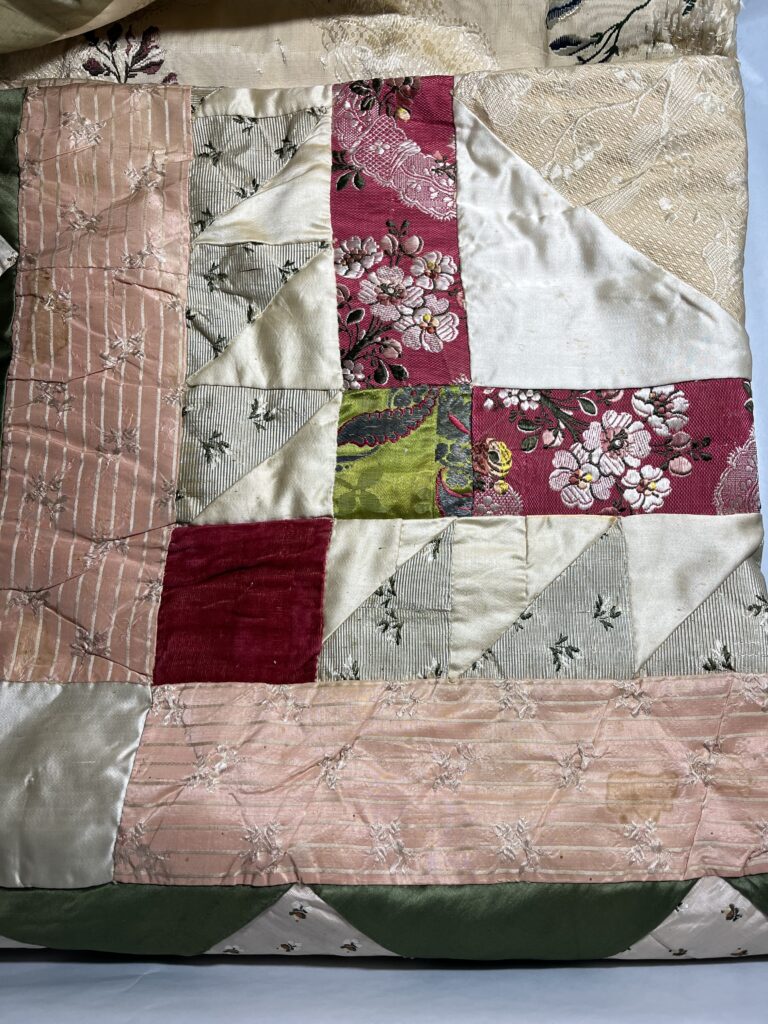

The Old South Meeting House also became a public institution at that time and began receiving donations. In the 1890s one important supporter, Mary Hemenway, gave Old South “a quilt made from fragments of Martha Washington’s dresses,” as Lori Fidler, Associate Director of Collections at Revolutionary Spaces, recently described in this article.

That’s just the sort of object that Americans oohed and aahed over breathlessly during the Colonial Revival. From the Age of Homespun! Touched by the great Washingtons themselves! But how reliable is its lore?

We know the quilt came to Hemenway from Fannie Washington Finch, an actual great-grandniece of George Washington. Her story:

There are also intriguing details about the quilt itself:

Furthermore, Fidler reports, “In her writings, Martha Washington mentions cutting up her garments and distributing pieces to family members and friends as mementos.” Finch couldn’t have inserted that into the historical record.

So on this item, I’m inclined to accept the lore.

And some of those were even authentic.

Others, however, were not. I retold the saga of a reputed Thomas Oliver portrait here, for example.

Among items donated to the Bostonian Society in its early decades, I’m skeptical about the machine-woven “Sons of Liberty flag.”

I worked with Dave Ingram on a report about a powder horn ascribed to Richard Gridley; we determined it was almost certainly a Colonial Revival–era creation.

The Old South Meeting House also became a public institution at that time and began receiving donations. In the 1890s one important supporter, Mary Hemenway, gave Old South “a quilt made from fragments of Martha Washington’s dresses,” as Lori Fidler, Associate Director of Collections at Revolutionary Spaces, recently described in this article.

That’s just the sort of object that Americans oohed and aahed over breathlessly during the Colonial Revival. From the Age of Homespun! Touched by the great Washingtons themselves! But how reliable is its lore?

We know the quilt came to Hemenway from Fannie Washington Finch, an actual great-grandniece of George Washington. Her story:

Fannie was born Frances Louisa Augusta Washington in Virginia in 1828. Her mother, Henrietta Spotswood, was the granddaughter of George Washington’s half-brother, Augustine, Jr., while her father, Bushrod, was the grandson of George’s brother, John Augustine. Fannie’s grandmother, Jane Washington, had made the quilt out of scraps she received directly from Martha.We also know from Finch’s letters in 1884–1886 that she was selling heirlooms from Mount Vernon, including this quilt, because of her “pecuniary condition.” In other words, she needed money.

There are also intriguing details about the quilt itself:

In 1979, a textile curator at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts examined the quilt, finding the silk pieces to be expensive English-made loom-woven fabrics, consistent with textiles worn by wealthy women of the 1700s. He mentioned that the designs represented a range of time periods, with larger floral patterns from the mid-18th century and tiny blossoms from the late 1700s. . . .Thus, Finch might have had a motive to concoct a connection between this quilt and Martha Washington—but the artifact itself really does contain the fabrics a wealthy British-American woman in the mid- to late 1700s would have owned.

In May 2024,…[Zara] Anishanslin noted that a fabric used in the quilt appeared to be an Anna Maria Garthwaite design. Garthwaite was a female silk designer who lived and worked in the Spitalfields area of London in the mid-1700s.

Furthermore, Fidler reports, “In her writings, Martha Washington mentions cutting up her garments and distributing pieces to family members and friends as mementos.” Finch couldn’t have inserted that into the historical record.

So on this item, I’m inclined to accept the lore.

No comments:

Post a Comment