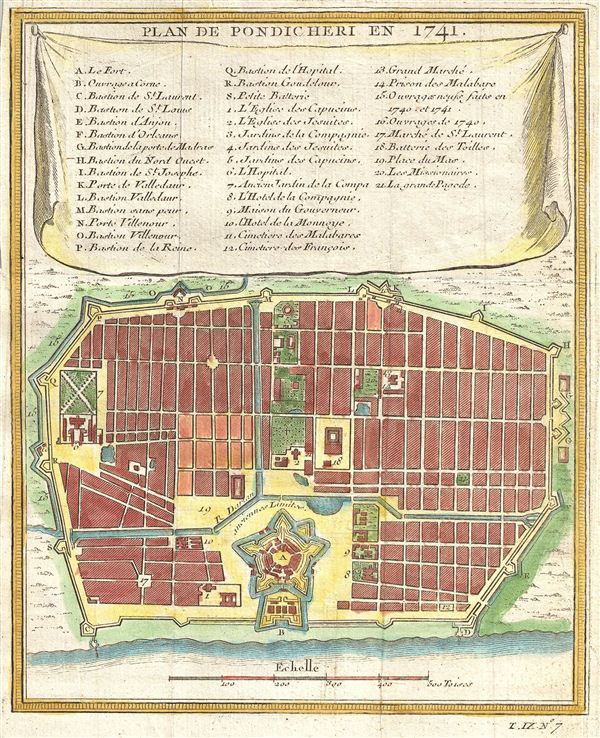

Two Deaths in Pondichéry

At Nursing Clio, Jakob Burnham examines two deaths in the French colony at Pondichéry, India, in 1726.

One was a French soldier named Le Bel who had thrown himself into a well and drowned. The other was a 75-year-old local man named Canagesabay, found hanging from a tree.

Both men had been ill, Le Bel with a “lung abcess” and Canagesabay with debilitating stomach pains. The soldier had made arrangements for his death days earlier while the local man’s sons reported that he had spoken of throwing himself into the street. So it appears both men became physically ill, despaired of recovering, and killed themselves.

Burnham writes that French law required “French subjects who were determined to have committed suicide to hang by their feet in the gallows; have their bodies dragged through the street; be denied Christian burial; as well as have their personal goods and assets confiscated.” Not that this was always applied to the letter.

However, there was a changing attitude:

In Pondichéry, the surgeon-general used just that phrase to explain the soldier Le Bel’s death. However, the same doctor said nothing about the medical conditions preceding Canagesabay’s suicide. And this different approach continued with how the authorities treated the two men’s corpses.

One was a French soldier named Le Bel who had thrown himself into a well and drowned. The other was a 75-year-old local man named Canagesabay, found hanging from a tree.

Both men had been ill, Le Bel with a “lung abcess” and Canagesabay with debilitating stomach pains. The soldier had made arrangements for his death days earlier while the local man’s sons reported that he had spoken of throwing himself into the street. So it appears both men became physically ill, despaired of recovering, and killed themselves.

Burnham writes that French law required “French subjects who were determined to have committed suicide to hang by their feet in the gallows; have their bodies dragged through the street; be denied Christian burial; as well as have their personal goods and assets confiscated.” Not that this was always applied to the letter.

However, there was a changing attitude:

By the seventeenth century, public officials in France and elsewhere increasingly concerned themselves with suicide as a matter of public order and as part of a larger effort to investigate the circumstances around suspicious deaths. This greater attention to the circumstances of death contributed to what has been called a “medicalization” of suicide, especially at the turn of the eighteenth century. Testimonies from investigations into reported suicides revealed that witnesses and family members began amplifying connections between chronic illness and suicide during this period. Official reports, witness statements, and even interviews with survivors made references to “melancholy, mental and physical maladies over which they reputedly had no control.”This led to the thinking that someone’s illness may have “transport au cerveau” (gone to his head) and led to suicide.

In Pondichéry, the surgeon-general used just that phrase to explain the soldier Le Bel’s death. However, the same doctor said nothing about the medical conditions preceding Canagesabay’s suicide. And this different approach continued with how the authorities treated the two men’s corpses.

No comments:

Post a Comment