Carp on “A figurative and literal tinderbox”

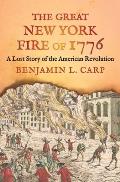

In a long article at the Smithsonian Magazine, Erik Ofgang discusses Benjamin L. Carp’s argument in The Great New York Fire of 1776: A Lost Story of the American Revolution.

As is clear from the article title, “Did George Washington Order Rebels to Burn New York City in 1776?,” this analysis digs into the question of why the city burned so soon after the British army returned.

This month will bring a couple more opportunities to hear Ben Carp speak about this and other Revolutionary issues. (He likes to prepare different lectures for different venues, so don’t be shy about signing up for both.)

Thursday, 18 May, 6:30 P.M.

Lost Stories: How the New York City Fire of 1776 Illuminates Unfamiliar Lives of the American Revolution

Fraunces Tavern Museum, in person and online

Register here

Tuesday, 30 May, 7:00 P.M.

Urban Geographies of the American Revolution

Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library, in person and online

Register here

As is clear from the article title, “Did George Washington Order Rebels to Burn New York City in 1776?,” this analysis digs into the question of why the city burned so soon after the British army returned.

“I feel that it was definitely set deliberately,” said Carp on a recent afternoon outside of Trinity Church, which has been rebuilt twice since the 1776 fire. A historian at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York Graduate Center, Carp knows he hasn’t proved this theory “beyond all reasonable doubt,” but he points out that legal standard isn’t the norm for historians. He believes many accepted historical truths—including the “dinner table bargain” of 1790, in which Thomas Jefferson supposedly brokered a deal between Alexander Hamilton and James Madison—are built on similar or flimsier evidence.The article tackles questions about the nature of historical evidence and changing perspectives.

In his meticulously researched, peer-reviewed book, Carp recounts how New York City, which was centered around modern-day Lower Manhattan and didn’t yet include any boroughs, was a figurative and literal tinderbox in the days before the fire. The vast majority of buildings were wooden. In the aftermath of the Continental Army’s retreat on September 15, the city was crawling with ardent Loyalists, New England radicals, British soldiers and Rebel spies—not to mention rumors that a fire was coming.

When the inferno finally broke out, many witnesses said they saw people starting smaller fires, carrying incendiary devices or interfering with efforts to put the fires out. These accounts are found in diary entries, contemporary newspaper articles and later testimonials. Additionally, Carp counts more than 15 distinct fire ignition points reported by witnesses.

This month will bring a couple more opportunities to hear Ben Carp speak about this and other Revolutionary issues. (He likes to prepare different lectures for different venues, so don’t be shy about signing up for both.)

Thursday, 18 May, 6:30 P.M.

Lost Stories: How the New York City Fire of 1776 Illuminates Unfamiliar Lives of the American Revolution

Fraunces Tavern Museum, in person and online

Register here

Tuesday, 30 May, 7:00 P.M.

Urban Geographies of the American Revolution

Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library, in person and online

Register here

No comments:

Post a Comment