Recruiting at Samuel Gettys’s Tavern

Yesterday I visited Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. What, you might ask, does that city have to do with Boston 1775?

After all, the boundaries of Gettysburg weren’t drawn until 1786, and it wasn’t incorporated as a borough for another twenty years after that.

Way back in 1761 a man from Ireland named Samuel Gettys settled at the intersection of roads between Philadelphia and Fort Pitt and between Shippensburg and Baltimore. He opened a tavern for soldiers, traders, hunters, and others traveling in that part of western York County.

When the Continental Congress resolved to recruit companies of riflemen to join the New England army besieging Boston, Gettys’s tavern was where most of the men of Capt. Michael Doudel’s company signed up, on 24 June 1775.

Those men marched out of York on 1 July, arriving in Cambridge twenty-four days later.

On 29 July, a letter back home to Pennsylvania reported, Doudel’s company was ordered “to march down to our advanced post, on Charlestown Neck, to endeavor to surround the enemy’s advanced guard, and bring off some prisoners, from whom we expected to learn the enemy’s design in throwing up the abattis in the Neck.”

Doudel led thirty-men to the right of the British position on Bunker’s Hill. By “creeping on their hands and knees, [they] got into the rear of the enemies sentries without being discovered.”

Meanwhile, Lt. Henry Miller led an equal number “in getting behind the sentries on the left.” The two lines of riflemen got to “within a few yards of joining” and surrounding the British advance guard.

But then “a party of regulars came down the hill to relieve their guard” and spotted Doudel’s riflemen. They fired from a distance of twenty yards. The Pennsylvanians fired back.

Then, it appears, almost all the soldiers dashed back to their own lines. The Continentals claimed “two prisoners and their muskets.” The British captured Cpl. Walter Cruise; there were soon rumors he was dead or executed, and it took well over a year before he made it back to the American side, as I’ve discussed elsewhere.

Shortly after that, Capt. Doudel fell ill, resigned, and returned home. Lt. Miller took command of the company for the rest of the siege of Boston.

After the war, the people of western York County started to agitate for their own governmental structure. In 1800 the state of Pennsylvania set off Adams County, named after President John Adams, and established the county seat as Gettysburg, named after the late tavern owner.

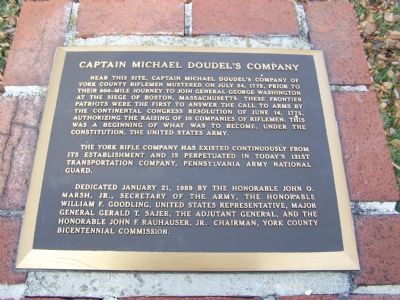

(The historical marker shown above is in York, where the Doudel’s company mustered before marching north. Fortunately, the area around where Samuel Gettys’s tavern stood has plenty of other historical markers and monuments.)

After all, the boundaries of Gettysburg weren’t drawn until 1786, and it wasn’t incorporated as a borough for another twenty years after that.

Way back in 1761 a man from Ireland named Samuel Gettys settled at the intersection of roads between Philadelphia and Fort Pitt and between Shippensburg and Baltimore. He opened a tavern for soldiers, traders, hunters, and others traveling in that part of western York County.

When the Continental Congress resolved to recruit companies of riflemen to join the New England army besieging Boston, Gettys’s tavern was where most of the men of Capt. Michael Doudel’s company signed up, on 24 June 1775.

Those men marched out of York on 1 July, arriving in Cambridge twenty-four days later.

On 29 July, a letter back home to Pennsylvania reported, Doudel’s company was ordered “to march down to our advanced post, on Charlestown Neck, to endeavor to surround the enemy’s advanced guard, and bring off some prisoners, from whom we expected to learn the enemy’s design in throwing up the abattis in the Neck.”

Doudel led thirty-men to the right of the British position on Bunker’s Hill. By “creeping on their hands and knees, [they] got into the rear of the enemies sentries without being discovered.”

Meanwhile, Lt. Henry Miller led an equal number “in getting behind the sentries on the left.” The two lines of riflemen got to “within a few yards of joining” and surrounding the British advance guard.

But then “a party of regulars came down the hill to relieve their guard” and spotted Doudel’s riflemen. They fired from a distance of twenty yards. The Pennsylvanians fired back.

Then, it appears, almost all the soldiers dashed back to their own lines. The Continentals claimed “two prisoners and their muskets.” The British captured Cpl. Walter Cruise; there were soon rumors he was dead or executed, and it took well over a year before he made it back to the American side, as I’ve discussed elsewhere.

Shortly after that, Capt. Doudel fell ill, resigned, and returned home. Lt. Miller took command of the company for the rest of the siege of Boston.

After the war, the people of western York County started to agitate for their own governmental structure. In 1800 the state of Pennsylvania set off Adams County, named after President John Adams, and established the county seat as Gettysburg, named after the late tavern owner.

(The historical marker shown above is in York, where the Doudel’s company mustered before marching north. Fortunately, the area around where Samuel Gettys’s tavern stood has plenty of other historical markers and monuments.)

No comments:

Post a Comment